The 10 Best Films of 2023 (by Andreas Babiolakis)

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Wow.

What a year 2023 has been for film.

It felt like we never truly recovered from the backlog that the COVID-19 pandemic created because we had to wait longer for most films to be released (or even produced). Once many of these films finally got released, perhaps the extra-long wait rendered a few of them disappointing (whereas a few titles, let’s be honest, were most likely dead upon arrival whether we wanted to admit that or not during our vulnerable mindsets these past few years). All in all, the 2020s have had a few brilliant films, but compiling best-of lists felt a little pressing because of how little we had to work with. Was this going to be the tone of the decade as a whole? Were we blaming the pandemic when this is far more indicative of a bigger problem? That problem is studios’ insistence on funding IPs and franchises over original ideas to the point that many singular filmmakers have had to dip their toes into blockbuster epics just to get by. In short, it just felt like we were getting the same cookie-cutter stories again and again, an overabundance of delayed releases during a wonky time in our history, and so many other issues. This decade felt doomed from the start, outside of a couple of films that sparked glimpses of hope in me.

2023 was the kick on the ol’ generator that we all needed. From indie projects to mainstream, box-office-topping delights, this year has been a resurgence in great cinema that cannot be ignored. I was tempted to make a top twenty-five films list, but instead, I will continue to try and boil down a best-of list just to ten titles just to prove the top-tier quality of what we got. You’ll spot many honourable mentions, mind you, because I want to shout out at least some of the other great titles that the year had to offer (which could have easily made the lists of the past few years). For now, I’d like to focus the most on the very best of 2023.

What did we get this year that was so good? Mainly, we had to have beloved directors come to kick our asses with some of their strongest projects in years (or, flat out, their best films to date). Additionally, we had a few filmmakers join in the conversation of contemporary greats with their terrific motion pictures that could even go toe-to-toe with the works of established masters. What these directors did was revitalize genre films during a time where genres seemed to feel like suffocating overindulgence that we got sick of. Consider that a straight-up comedy dominated the box office, a re-contextualization of the romantic drama became the breakthrough indie hit of the year, a western held audiences in their seats for nearly four hours, a biopic didn’t play by the rules and performed tremendously, and a courtroom drama wound up being the sleeper hit of the year (if Cannes didn’t jumpstart its successful run, mind you). We even have an animated film that has been shaking audiences and critics worldwide. Sure. We had some bad releases this year as well (quite a few, as per usual), but why focus on the negative when we’ve been praying for a year this good since the start of this decade?

Congratulations, cinephiles: you’ve earned this year. Here are the ten best films of 2023.

Note: I will not be including 2022 releases that got wide releases or that I didn’t catch until earlier this year, so you won’t be seeing titles like All the Beauty and the Bloodshed or Close.

Honourable Mentions (In Alphabetical Order):

-Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret

-Asteroid City

-Barbie

-Beau is Afraid

-The Delinquents

-Fallen Leaves

-The Killer

-La chimera

-Passages

-The Royal Hotel

-Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse

10. The Boy and the Heron

Hayao Miyazaki returned after a ten-year hiatus from the industry with the gorgeous coming-of-age fable The Boy and the Heron. Equal parts goofy and grim, this transition from childhood to maturity through the damnation of grief is Miyazaki’s most surreal effort to date: a dismantling of the infrastructure of our minds when it comes to setting up barriers post-trauma. Miyazaki projects much of his own life — from his youth to his present state trying to provide wisdom to his formative self — into the film, creating a personal parable about living; never take life for granted; always keep in touch with your inner child. This has been his umpteenth supposed swan song, but should this actually be the last we ever see of Miyazaki, The Boy and the Heron spellbinds us with purpose and spectacle in the name of urging us to face the darkness of life and persevere; it’s a beautiful final thought to grace us with.

9. Past Lives

Celine Song’s debut, Past Lives, wins the award for being the surprise hit of the year. Way before Barbenheimer came close to crashing down our doors, the awards season ascended, or so many large-named returns took place, Song’s romantic drama about what-ifs and hearts stuck in the grey area pulled us out of the plethora of franchise nonsense earlier in the year. Through poetic filmmaking, the silent cries of Greta Lee’s Nora’s soul, and the concept of inyeon in Korean culture (the notion that people are designed to meet or be together by fate), Song makes a simple film that shakes us to our core. Why does life have its own plans if we cannot fulfil what we desire? No matter how much comfort Song assures us for the finale of Past Lives, it only stings more and more the longer you think about it. We can only control what we do, not how we feel, and Past Lives possesses this message in spades.

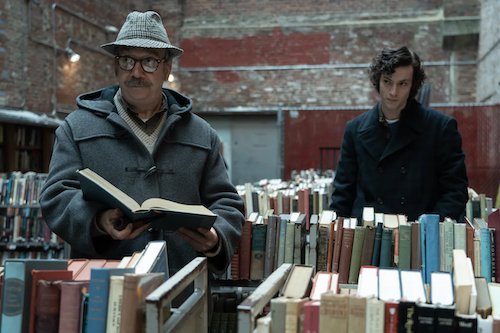

8. The Holdovers

If anyone can evoke the love-hate relationship many have with the stresses and unions of the holiday season, it’s Alexander Payne, whose latest feature, The Holdovers, is a fine dramedy that understands how it feels to feel unconsoled during a time of year that enforces togetherness to your face. As life forces our three protagonists to suffer abandonment in different ways (lovelessness, war stripping you of a loved one, et cetera), our hearts flood with joy seeing these lost souls unite on Christmas (yes, even amidst all the bickering and dysfunction). Still, Payne isn’t one to get too sappy, and reality saves its swiftest slap to the face for last as The Holdovers takes the love that has gestated and forces it to be used as a sacrifice of devotion amidst a dilemma; perhaps this symbolic case of career seppuku to save another was the greatest Christmas gift of all in The Holdovers.

7. May December

How do you take on a true story as disturbing as that of Mary Kay and Vili Letourneau and turn it into a film that isn’t either sterile or vile? You can take Todd Haynes’ unorthodox approach in the meta-commentary May December: a stylized melodrama, black comedy that is so self-aware that it caves in on itself, breaking the foundations of what “based on a true story” and method acting can be. Always one to shatter the conventions of film via his underground cinema roots, Haynes subverts expectations via the best Persona homage since Mulholland Drive. May December is so focused on going against the grain that you can’t even ascertain what this film would look like under the direction of someone else. This is the sole way to craft a film about a story this disturbing: through aesthetic hyperbole, tonal ambiguity, and a film that already feels like the end product (this isn’t so much a film about a biopic being made as much as it is the film referencing itself in a Frankensteined, satirical case of ambivalence on how moral true crime films actually are).

6. Oppenheimer

In order to best understand what makes a good biopic, it may be worth deconstructing a typical one and reassembling it in a new way. Christopher Nolan does just that with Oppenheimer as he strips both the factual elements away from the wide-eyed fascination surrounding a subject and allows both the objective and subjective versions of Robert J. Oppenheimer’s rise and fall. Was Oppenheimer a hero or a monster? The film sees him as both and understands that it is the state of the world that created this dichotomous opportunity; if it wasn’t him, someone else would have been in his very spot. Released during a particularly hostile time regarding global politics, Oppenheimer is a reminder that we are our own destruction as a civilization, and yet we are all forever searching for one single person to blame. Our progress is our demise.

5. All of Us Strangers

Andrew Haigh continuously searches for the true meaning of love, and his best experiment yet comes in the form of All of Us Strangers: a relentlessly heartbreaking depiction of loneliness and cathartic salvation. Exploring grief and isolation post-pandemic via lush aesthetics and a weeping soul, the director channels conversations with the ghosts of yesteryear via a show-not-tell approach that makes us feel every ounce of what is transpiring throughout these fever dream visuals. Equal parts stunning and saddening, All of Us Strangers acknowledges that we are all capable of feeling extreme loneliness at any given point in our lives. Life is beautiful, but it feels like purgatory when we live it alone. Are we ever truly alone? That’s what All of Us Strangers wants to assure us of: the dearly departed will forever be with us either through faith-based means or via the stardust that unites us all. We are all strangers to one another, but we are familiar in this sense; we are united in existentialism.

4. Anatomy of a Fall

It’s obvious that Justine Triet’s Palme d’Or winner Anatomy of a Fall is a terrific film once you finish watching it, but I don’t think we realize how powerful it is until we really think about it. Months after I have watched it, I am still cursed by its open-ended limitlessness: we never get a definitive answer outside of what the court decides. Like an A Separation for the 2020s, Triet asks us — similarly to what Asghar Farhadi did with the Iranian classic — to dwell on the moral complexities of legal conclusiveness in a world that is too intertwined in all that is in between black-and-white matters. It doesn’t matter who is actually guilty in Anatomy of a Fall. It’s sad enough that we watched a marriage plummet, joy corrode, and a family destroy itself; the focal death was just the final straw. In that same breath, we’re watching morality collapse and the downward spirals of the legal system, the media, and more: all meant to be beneficial systems to help us, not make us hate each other even more.

3. Killers of the Flower Moon

We’ve been waiting for Martin Scorsese’s western epic Killers of the Flower Moon for years, and it most certainly did not disappoint, resulting in one of his best releases in the twenty-first century. What we may have expected — had we not read David Grann’s non-fiction novel of the same name — was a dynamic crime film full of sin and action. What we get instead is much more rewarding: a slow-brooding look at guilt, and the many (many) instances for a terrible man to become a better person before he went too far. As we watch white opportunists slowly engulf the land and society of another, we watch tradition, culture, and people die. At least showdowns at high noon are quick; this version of a Western slaughter is devastating. It’s also very much real, as we watch historical lessons we should have already known. Killers of the Flower Moon is horrifying, crushing, and unforgettable.

2. Poor Things

Even though it is a masterful film, it appeared as though Yorgos Lanthimos may have been easing up a little bit on the levels of cynicism and the absurd that he’s known for with 2018’s The Favourite. It was my favourite film of his, even though I was worried that he would never be unhinged again. I was so painfully wrong. Poor Things is as insane as the Greek director has ever been. Additionally, it is as forward-thinking as The Favourite in its stance on societal sexism, systemic imbalance, and the pursuit of a voice within a world that won’t grant you one. As batshit crazy, satirically buffoonish, fantastically strange, and darkly political as the film is, its greatest triumph is the hero arc of Bella Baxter who never once let civilization’s stupidness stop her from becoming a fully realized, independent spirit. Equal parts bonkers, moving, and shocking, Poor Things is as idiosyncratic as contemporary cinema can get.

1. The Zone of Interest

There was no other film that stuck with me this year as much as Jonathan Glazer’s haunting exhibition of the curse of complete compliance known as The Zone of Interest. For months, I had Mica Levi’s demonic score from the underworld pulsate in my head, the ghostly camera angles and precise editing that make us viewers feel like omnipresent spirits gawking at an atrocious circumstance, and the tiny hints of slaughter that grew into undeniable red flags; the audacity of pretending that the massacres of entire nations are happening just over the fence of your fancy property aren’t happening is unlike any other. Impeccably made and permanently effective, you enter and leave screenings of The Zone of Interest a different person: one astounded by how well this film is made, and one disappointed in how awful we as a species can truly be. As impactful as cinematic art can get, The Zone of Interest is not just one of the best films in a year of terrific motion pictures: it is certainly the best film of 2023, which speaks a lot as to how vital, ghastly, and harrowing this film is. Whether you love the film or cannot find yourself attached to it because of its challenging nature, I can promise you that, either way, we’ve never seen anything like The Zone of Interest.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.