Filmography Worship: Ranking Every Wes Anderson Film

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Filmography Worship is a series where we review every single feature of filmmakers that have made our Wall of Directors

When people think of Wes Anderson, they automatically leap towards his visual, symmetrical aesthetic, his deadpan cast of characters (and their large numbers, mostly consisting of famous and reliable faces), and his sophisticated sense of style and humour. While it is easy to resort the Texas native to these tropes because of his singular approach to them, I feel like Anderson gets short-changed when reflected upon in such a basic way. The truth is Anderson is a major cinephile whose influences come from all corners of the medium. His early works evoke his affinity for French New Wave (especially a film like François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows). His visual style is straight from the popup playbook of Karel Zeman who in turn was forever channelling the imaginative visions of writer Jules Verne (he would adapt his work as well). These are only the beginning. Compartmentalizing Anderson’s style as one fixed constant feels wrong as each of his feature films has its own set of inspirations throughout. It feels simple to lump all of his films into one pile and call them all his own in a general sense, but it’s flat-out unfair to the identities that all of his films possess individually. Let’s give this loveable auteur his dues today. Here are the feature films of Wes Anderson ranked from worst to best.

12. The French Dispatch

While still a good film (not a great one), The French Dispatch winds up at the bottom of this list. I appreciate the concept (of having a series of stories throughout the titular newspaper’s lifetime encompass the scope of a deceased editor’s dream coming to fruition), but I think the execution is so-so: we never really get connected with any of these characters, the histories they embody, and anything else in what is arguably Anderson’s most technically impressive feature. I’ve described The French Dispatch before as a trinket you can pick up from the Wes Anderson gift shop when you’re on the way out from other main attractions, and I still stand by this statement years later. If you love Anderson’s films, The French Dispatch is a neat feature to watch at least once. Having said that, I feel like even a short film like Hotel Chevalier is much more fully realized than any of the vignettes here no matter what aesthetic ideas are tossed at you (like the fancy animated sequence during “The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner.” The French Dispatch is a series of missed opportunities wrapped up in a fancy bow that at least feels like decent escapism in Anderson’s signature way.

11. The Phoenician Scheme

Like a second-go at The Grand Budapest Hotel, Anderson’s The Phoenician Scheme is highly rich in its complexities and literary nature; this seems to be the case at first. Unlike The Grand Budapest Hotel, The Phoenician Scheme buckles enough underneath the weight of Anderson’s attempts to make something layered and thought provoking. Despite showcasing some strong allusions and photographic similarities to the works of Andrei Tarkovsky, Luis Buñuel, and even Sergei Parajanov, Anderson’s answer to introspective and intellectual navigation surrenders to the auteur’s fixation on whimsy and silliness; I don’t expect The Phoenician Scheme to be gritty and cynical, but the film could have benefited from more maturity. Even so, to even see an espionage film told in such a peculiar way is a treat, and — like many of Anderson’s films — there may be an inability to shake off the Phoenician Scheme’s strengths that can lead to it being reevaluated years down the road (every Anderson film has its fan base, after all).

10. Moonrise Kingdom

Like Anderson’s answer to Ingmar Bergman’s Summer with Monika, Moonrise Kingdom is a coming-of-age tale involving youths departing civilization and claiming their hideaway location. Naturally, Anderson’s film is much cuter than Bergman’s dose of reality, but that may be the thing: Moonrise Kingdom may be a teensy bit too cute. It doesn’t fully get in the way of itself, however. I still find that there are enough meaningful moments — especially from the adults who are as lost as their own kids in this town — that make Moonrise Kingdom a great film throughout, and I do find that this film being Anderson’s most adorable is precisely why it winds up being a favourite for some. I think Moonrise Kingdom captures childlike innocence the best out of all of Anderson’s films, and it is great to revisit when I want an inoffensive, spirited film about being young. Even though Moonrise Kingdom is this low, I think it is a strong film (but I also wouldn’t call any Wes Anderson film outright bad). There’s a lot of heart to this escape from reality, and it’s most certainly an optimistic film in the face of adversity that we can use right now.

9. Asteroid City

Asteroid City may very well be Anderson’s most pessimistic film, but even then he is looking for all of the bright spots within animosity. Created during a particularly heated time on planet Earth (either due to political discourse or in a more literal sense with the climate changing), Asteroid City dissects the purposes of our planet’s inhabitants as individuals: why are we all here, and what are our missions? This is told in the form of a behind-the-scenes look at a televised production, so you see a fictitious tale about a stargazing convention being swept away by the possibilities of the unknown, people facing the grief of lost ones in their ways, and actors remarking on their performances and wondering what their drive is (both on set and in real life). I find the final third of Asteroid City to be particularly touching as Anderson finds his own bright and inspired way to assure us that even in the darkest times that everything will be okay.

8. The Darjeeling Limited

I initially found The Darjeeling Limited to be quite a weak film, especially when it stands in the shadows of the sister short film Hotel Chevalier (which may have some of Anderson’s most serious, visceral storytelling he’s ever put to screen). Years later, I revisited this soul-searching quest of three brothers that have become estranged and unrecognizable to one another and I think it has aged fairly well. I think it took me to go through my own tribulations and life-altering experiences to understand The Darjeeling Limited and why the characters act the ways that they do (typically with pure instinct and no divine reason; I initially found this to be lazy writing but I instead feel as though this is the capturing of the waywardness of life). Once we see the three brothers learning to live with one another and take this Indian trek together as a unit, we see what was always at the heart of The Darjeeling Limited: a call to action to appreciate your family. They may not always be around. You may not always see eye-to-eye. You’ll also never have one again, and it’s worth cherishing who you’re related to no matter how different you are.

7. Bottle Rocket

Wes Anderson had a similar start to Terrence Malick: a strong debut film that feels more orthodox than anything else they would make ever since. While Anderson didn’t make a first feature as sensational as Badlands, he did have a strong debut with Bottle Rocket: a whimsical crime film that sucks all of the danger out of a usually dangerous genre. Even though this feels like the least Wes Anderson film the auteur has ever made, there also wasn’t another film that felt like Bottle Rocket when it came out: a film about thieves and their escapades that felt fun, hilarious (yet not stupid), and as though it picked up on all the weird instances that make us human (no one in Bottle Rocket feels untouchable or invincible, and yet you know that you won’t find anything too gruesome here). It would take his next feature before he would start to exercise his visions, but Bottle Rocket allows us to see three major early wins for Wes Anderson: he pulled off turning his acclaimed short film into a realized feature, he formed partnerships he would never lose (the Wilson brothers, whose careers also took off because of this debut), and he would begin to challenge then-contemporary cinema with his tropes (the extreme closeups of the note of projections with Owen Wilson tapping each portion with a marker is pure Wes Anderson before we even knew what we were in for). This was only the beginning, but Bottle Rocket stands alone and tall nonetheless.

6. The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou

The first time I saw The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, I didn’t get it. I was a young teenager and I thought this tribute to the combination of oceanographic science and filmmaking was a sugary, loud mess. I put it off for years and refused to rewatch it, certain that it was Wes Anderson’s worst film. Having revisited it as an adult, I couldn’t have been more wrong. To be fair, this was the first film to go full-on Wes Anderson to such a degree, and I don’t think I was ready for it yet (neither were many, considering the lukewarm reception it once got despite having a major fanbase now). I didn’t connect with these lost souls that strived to chase life and its oddities, nor did I appreciate the emotional core hinged around the topic of loss here present in the final act. Additionally, I took the comedy for granted: this may be Wes Anderson’s funniest film to date, as it is full of brilliant quips (and so many that you may miss some the first watch). Also getting familiar with the works of Jean Pailevé and Jacques Cousteau allowed me to understand what Anderson was getting at here: the wonder and self-absorption of underwater scientific filmmaking. I used to think The Life Aquatic was overlong, abrasive, and pretentious. I understand this film now as thorough, ambitious, and self-aware; perhaps it was me that was being too serious. I was wrong. I was so wrong before. Count me in on this squad. Give me a wetsuit and one of those red beanies.

5. Isle of Dogs

When Anderson stated that Isle of Dogs was a tribute to Akira Kurosawa, it initially felt like a lazy claim considering the Japanese connection found in the film. After finishing Anderson’s second animated feature film, I finally understood what he meant. Kurosawa was a particularly empathetic filmmaker who placed his characters in the kinds of turmoils and revelations that his viewers may understand, even if they were never samurais (which is likely the case). Isle of Dogs is Anderson’s most emotional film and the first time where the director comments on the fearful future of our planet. We may not be dogs, but we understand these canines’ concerns throughout this dystopia. This film also possesses the kind of poetic nature that some Kurosawa films boast like Ikiru or Dreams, as Anderson searches for youth, peace, and paradise in this concerning prediction of our reality (the virus spreading around is sadly prophetic concerning what we’d face only a couple of years later with COVID-19). Adorable, moving, and worthy of much discussion, Isle of Dogs may be Anderson at his most serious (which kind of says a lot, in a good way).

4. Fantastic Mr. Fox

It feels a little cheap to have both of Wes Anderson’s animated features ranked back-to-back, but I do think very highly of them both. I’ll give Fantastic Mr. Fox the edge by just a hair. Firstly, it is arguably the best adaptation of a Roald Dahl novel I’ve seen (sorry Matilda fans). Anderson and Noah Baumbach (the latter helped co-write this film) capture the late author’s tongue-in-cheek tone while crafting their dialogue and moments to add to the original story (the idea that “cuss” represents actual swear words in this film is a hilarious delight). Secondly, I feel like Anderson can target ideas, events, and jokes here that he could never attempt before given the limitless nature of stop-motion animation. Lastly, the titular Mr. Fox and his change of heart in the face of the endangerment of his family and community is nicely handled: this may be a family film but Anderson and company never pull any punches to sanitize the severity of moments in fear of having a rating change (I think the gun-toting farmers drives this point home even more). I still find Fantastic Mr. Fox tame enough to show to kids, and I appreciate that the lessons here are real ones that can shape any first-time viewers.

3. The Royal TeneNbaums

When I was eleven years old, I was slapped in the face by a strange film called The Royal Tenenbaums. I had no idea what I had watched or why I liked it, but I needed to see more. The problem with these kinds of first impressions is that some films may let you down on subsequent watches. Not this one. The Royal Tenenbaums is smack dab in the middle between the Wes Anderson of old and new: still slightly rooted in a reality that we can identify with while being aesthetically and tonally quirky to the point of feeling detached from this world. I know that all Anderson films feel different, and you can mark The Royal Tenenbaums maybe as his most mature film; even still, there are a lot of goofy shenanigans here that will have you equating the strange people here with misfits from your own life. If there was ever a film that many filmmakers tried to imitate Wes Anderson’s, it’s this one, particularly with the mumblecore, out-there indie films that dreamed of being the next Royal Tenenbaums. Most of these pursuits were in vain. If many Wes Anderson films target coming-of-age bliss, then The Royal Tenenbaums is his of-age tale of disappointment and self-loathing, and I wouldn’t want it any other way. Not many films feel like they appeal to my adultly dark sense of humour and my inner child’s imagination like this one.

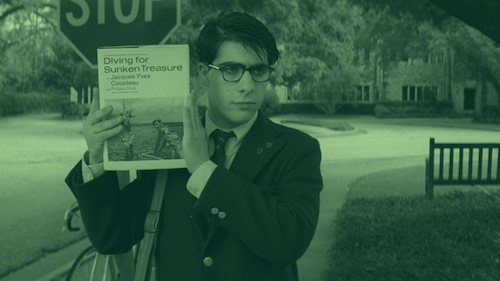

2. Rushmore

While not as preliminary as Bottle Rocket or as far along the way as The Royal Tenenbaums, Rushmore is in between the stages of filmic evolution by Wes Anderson. Even though he was still finding his footing, Rushmore is beyond confident and realized enough that it is an early masterpiece by the then-budding director. He translates the mischievousness of the French New Wave and the self-diagnosed genius of many French New Wave viewers of yesteryear (sorry, but it’s true) into tangible materials, and shoves them into a blender to create a coming-of-age tale of a gifted teen that actually doesn’t know everything. Rushmore feels a little bit like a diorama: a staple of nearly every Wes Anderson since. What sets it apart is the high school setting, as if we are getting a depiction of high school from an actual high school student. We don’t (considering Anderson was far from a teenager when making this feature), but the illusion is as strong as it can be. Not only was Rushmore a remarkable breakthrough for Anderson, but it has aged perfectly as one of the finest coming-of-age and high school films of all time, a major highlight of the nineties, and a comedy-drama that stands alone. Anderson would deviate into an even stronger aesthetic style so he’ll likely never return to this place, but I also don’t want him to: Rushmore feeling unlike anything else just makes sense.

1. The Grand Budapest Hotel

Now that Wes Anderson has ascended into a whole new realm of dollhouse filmmaking, he has released several fleeting features. Then there’s The Grand Budapest Hotel: his magnum opus. As aesthetically rich and comedically bonkers as ever (if The Life Aquatic is Anderson’s funniest film, this is a close second thanks to the screwball antics), The Grand Budapest Hotel already stood a great chance at being ranked highly. There’s also that emotional angle that some of his films (Isle of Dogs, for instance) carry that is viewed over time: readers discovering conversations about memories of yesteryear (it’s a confusing set of layers, but it makes sense through rose-coloured glasses and with heavy hearts). Finally, there’s something that most other Anderson films are lacking: danger. Every Anderson feature has conflicts, but you feel as though things will turn out for the best by the end of these stories. In The Grand Budapest Hotel, you know that Zero Moustafa himself will turn up in a good-enough place (given the fact that he is reflecting on his past). Characters find themselves in legitimate dilemmas and pickles in this film while there is a fascist uprise, fingers are pointed surrounding death and thievery (where is Boy with Apple?), and people are hunted. Still, this is a Wes Anderson film so The Grand Budapest Hotel is still more fun than it is scary (although the “fingers” moment is legitimately grim for an Anderson film and I love it), so what we get is a neo-screwball extravaganza tied together by nostalgia, love, respect, and the sadness when all three are endangered. The Grand Budapest Hotel is as riveting as it is inviting, exciting, and hysterical, and it is currently Wes Anderson’s magnum opus.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.