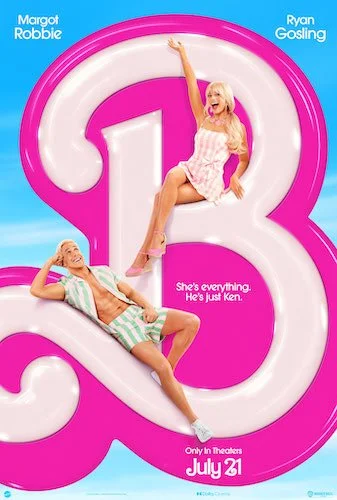

Barbie

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Warning: This review contains minor spoilers for Barbie. Reader discretion is advised.

I was eight or nine years old when I saw a specific chain of Barbie doll commercials during my Saturday morning cartoon binge-watches. I recall being visibly angry when the tagline “Barbie: It’s a girl’s world!” popped up on the television. The first few times the commercial appeared, I was furious. Why can’t it be a boy’s world too? Don’t we matter? It was maybe the fifth or sixth time the commercial appeared on my television set that I began to recognize that there was a huge problem. I was getting mad at a harmless tagline for a commercial that was aimed at making girls feel wanted and accepted. Maybe part of this hostility comes from the ways that children are brought up by society: a divide via products and traditions that aimed to condition us into thinking we have to be different. All I knew was something felt off. At the time, I had a mother I loved and two sisters I didn’t want to see fail in the world. As an adult, I identify as a feminist and I feel like this realization at such a young age was perhaps where that journey started. There are still so many regulations that work against women in society, be they openly apparent or in the background. To this day, I feel embarrassed that I was getting so worked up over something that wasn’t even meant for me.

It comes as no surprise that Greta Gerwig’s highly anticipated film, Barbie, is meant for all to see. Not everyone will want to see it, and some fragile snivellers will obviously decry this film as an attack on men (Ben Shapiro, you are one pathetic, sad wimp for feeling this threatened by a film). None of this matters. Gerwig made this film for all; those who want to watch and listen to its message will get something substantial out of it. I don’t even mean in a shallow sort of way. Gerwig and her partner Noah Baumbach (who helped co-write this feature) put lots of thought into this film. Lots of thought. You can see it at all times, particularly after the opening twenty minutes or so (the footage you’ve seen countless times in promotional trailers). Barbie is packed with idea after idea, all with the additional aim to have the film’s messages not abstruse at the same time. What we get is what we came for (a journey into Barbieland, and having Barbie and Ken enter the real world), but we also get so much more. Gerwig could have settled for one statement (about the mixed feelings about Barbie’s legacy and impact on females, about patriarchal injustices in the world, and/or the need to highlight mental illness when addressing youths and adults so everyone feels seen and tended to). Instead, she chose to cover as much ground as possible. She got to make a BARBIE movie that would reach millions of viewers worldwide. It was her opportunity to say what needed to be said, and she seized it.

Barbie could have been single-note in nature and with one major statement to make. Instead, it vows to use its podium to cover a lot of different topics.

Barbie (well, Stereotypical Barbie, played by Margot Robbie) wakes up every day with a wide smile on her face. She enjoys her morning routine, heading to the beach to say “hi” to all of her friends (all the other Barbies, all of the Kens, and the one-offs like Midge and Allan, to name a few), and then having a girl’s night in the evening. She wakes up every day and accepts the same cycle of joy. One day, her tip-toed foot form collapses and she becomes flat-footed. She accidentally drinks expired milk. She even falls off of her balcony, instead of floating down like she typically does. Maybe this all has to do with her weird episode from the night before, where she began to contemplate the concept of death. It’s apparent that something is off. This is when we learn that these dolls are actually being played with: Barbieland is generated by the imagination of others (mainly children that play with their dolls), and whoever is playing with Stereotypical Barbie is making her think dark thoughts. Meanwhile, her Ken (Ryan Gosling) is feeble-minded but well-intentioned, yet he is clearly experiencing an inferiority complex of some sort, likely because he is in love with Barbie and she won’t give him the same time of day, and because Kens are seen as plus-ones to the Barbies in this world: they can’t exist on their own or serve their purposes.

Barbie is told by Weird Barbie (a variation that has been bent out of shape by whoever is playing with her, with her hair chopped off and marker makeup stained on her face) that there is a real world out there, and Barbie must find out who is making her have these existential issues. You’d think it was a child, but it’s actually the adult Gloria: an employee at Mattel that is coming up with new ideas for Barbie and is expressing her very-real concerns whilst designing. Barbie and Ken (who snuck into Barbie’s car for the ride) enter the real world to find out what’s going on. This leads Barbie and Ken down separate paths. Barbie winds up at Mattel’s head office where she comes across the CEO (a pathetic, sexist leader played quite well by Will Ferrell). He wants to lock this Barbie away in a box; she realizes this quickly and vows to head back to Barbieland. She meets Gloria and her daughter Sasha (who initially hates Barbie and the backwards qualities of these dolls), who comes with her to try and fix things for Barbie. Ken, on the other hand, discovers that the real world is mainly run by men. This is a nice change of pace for him, and he studies patriarchy (as much as he can, I suppose) and promises to take these learnings back to Barbieland: this will now become a man’s world.

I don’t want to go into too much more of the story but believe me. There is a lot more. What we got in the trailers was just the tip of the iceberg, and Barbie felt like it was never-ending in the best way possible. What I think needs to be brought up first is how this still feels like a loving tribute to the Barbie doll whilst being a tough discussion about it at the same time. For as much as Gerwig discusses pretty serious issues with young audiences watching, she’s also introducing them to why she loved Barbie dolls growing up. There are a lot of details here, from obscure doll models and accessories to specific ideas that make every single style of play present here (from dolls being drawn on, to toys being flung in the air and the awkward ways they would fall afterward). There are many attentions to detail, and this leaks into the storyline as well (don’t think we didn’t notice the Birkenstocks reappearing at the end of the feature). Barbie gets silly, almost unbelievably so, but it has earned its goofiness after what seems like countless hours of world-building. Barbieland comes to life not just through nostalgia but organic progression as well. Those that never grew up with these dolls will feel hypnotized. Those that did will feel their childhood dreams come back to life with the biggest rush of nostalgia.

Barbie isn’t afraid to get meta and profound, even amidst all of the goofiness and nostalgia.

I was liking Barbie a lot and viewed it as a fun take on feminist talking points until the final act, where Gerwig begins throwing the curveballs that render this film as touching as it is hilarious. From that emotional montage to the inclusion of Ruth Handler’s legacy in such a meta way, Barbie begins to blow any expectations we had away. Whether you like these choices or not, you cannot deny that Barbie went to places you could not foresee. Barbie isn’t edgy, but it is most certainly daring. It never talks down to its audience, be you a child or an adult. Its depictions of threatened masculinity are also handled well as well: Ken is never really a villain as much as he is a vulnerable person that does bad things through misguidedness. If you want to view this film as an attack on men, go ahead and play the victim card. This is a celebration of women, and that shouldn’t be threatening to you.

Barbie gets down into the crux of the grey area surrounding these dolls. They’re meant to be empowering as you can make them have any profession, yet they compartmentalize what females are supposed to be themselves (furthermore, they were targeted solely for girls which isn’t fair for all of the identities that wanted to grow up with similar dolls). Women are not just taught to fight for the affection of men: they’re primed to compete with each other as well. Ken dolls are always advertised as accessories for Barbies (their add-ons, so to speak). Feeling existential dread is always shrugged off, yet we should be having these discussions and knowing we’re not alone. Also Allan. Barbie gets into some tricky territory with what it is discussing down to the actual — albeit brief — discussion of genitalia (yes, really), but Gerwig is willing to go anywhere possible with this film and that is commendable enough.

At its heart is near-perfect casting, particularly the three leads. Robbie and Gosling embody the typicalness of Barbie and Ken whilst also giving both characters some much-needed emotional range to add some actual flesh to these plastic dolls. There’s also America Ferrera as Gloria who acts as the voice of all women in the real world for the majority of the film; she is given a highly important monologue that silenced my sold-out theatre full of excited, seat-shuffling kids and their eager parents (she obviously nails it). Along with all of the other cast members and the unreal production and costume designs, Barbie comes to life, is equal parts funny and emotional, and as fully fledged as this kind of film could possibly be. Let’s face it: a Barbie film was going to be seen. Gerwig made sure that it was an important watch. We all likely had our expectations, and Barbie still went further.

From one of the smarter parodies of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (one that mirrors the Dawn of Man sequence as the tongue-in-cheek shift in female roles via the launch of the Barbie doll) to that shocking final joke that had us all laughing the hardest, Barbie is thoroughly witty, committed, and loving. It adores its source material whilst acknowledging the problems surrounding it. It has a lot to say but trusts its audience without ever barking at it. It dishes out many laughs but dials it back when it is time to get serious. Barbie could have just been neat. It will instead be one of the year’s most beloved films, and rightfully so. Barbie was Greta Gerwig’s to play with, and if it wasn’t clear before it certainly is now: she is one of the more imaginative and sagacious filmmakers of this new generation.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.