Ten Terrific Film Adaptations of Impossible-to-Adapt Novels

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

August ninth marks National Book Lovers Day, and I will use this opportunity to pose a notion I have always held: films hold as much artistic and narrative influence as novels do. Having said that, both mediums are extremely different in their approaches to storytelling, and the translation between both art forms doesn’t always work out. There are enough films that have been converted into textual form that lose something in the process. We don’t even need to get started on the number of film adaptations that suffer or completely miss the point or poise of the novels that they are meant to replicate. Of course, numerous film adaptations work, but their source material novels usually have enough descriptions or details to help make the transition a little easier.

I instead want to focus on the successful films that take on some of the more challenging novels that seemed impossible to adapt. What makes these novels impossible to adapt on paper? Their difficult prose, their lack of straightforward cohesion, their ambition, and many other literary devices just do not seem to work in any capacity outside of textual form. I’ll ignore the impossible-to-adapt novels that either resulted in so-so films (Catch-22, Slaughterhouse-Five, Ulysses) or outright travesties (Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close, The Dark Tower, The Lovely Bones). Of course, I am also ignoring the countless amounts of films that are great adaptations of novels (so you won’t find To Kill a Mockingbird, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Next, et cetera, here). Finally, I’m trying to ignore the films that are based on novels but in a remote sense (so I cannot consider Brazil for George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, but instead the more-direct adaptation of the same name by Michael Radford, which sadly didn’t make the cut). Which novels seemed impossible to turn into feature films? Which directors took on these challenges and won? Here are ten of my picks.

A Clockwork Orange

Anthony Burgess’ polarizing novel, A Clockwork Orange, is one of the most ferocious reads I have ever had. Written entirely in the fictional language of Nadsat, this story follows the delinquent Alex on his diabolical escapades in a futuristic society where Russia won the Cold War. Because of the difficulty of the Nadsat language and the extreme violence found within this philosophical text (one that asks whether it is better to brainwash criminals into sterile, upstanding citizens, or to allow them to fester and rot in prison), A Clockwork Orange is not the easiest film to picture outside of this novel. Of course, Stanley Kubrick is no ordinary filmmaker. Of all the adaptations he took on (excluding his major deviations like Dr. Strangelove and The Shining, and his attempts that aren’t his finest works like Lolita), A Clockwork Orange is his most faithful (ignoring the changed ending, of course). As risky, traumatizing, and ambitious as Burgess’ novel, Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange is a shocking film released just in time: during the rise of the New Hollywood movement.

Blade Runner

The works of Philip K. Dick have been adapted time and time again to varying results (there may also be a reason why Ubik hasn’t been touched with a ten-foot pole by filmmakers). One of Dick’s most cherished — and intense — works is Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?: a difficult conversation about the future of artificial intelligence and whether or not androids are worthy of moral compasses like humans. If this sounds familiar, it’s because Ridley Scott’s science fiction magnum opus, Blade Runner, is an adaptation of this novel, at least in a loose sense. One thing Scott maintains is Dick’s chilling, eerie sense of storytelling that makes you feel uneasy at each and every turn in this dystopian projection of where society is headed. In case Blade Runner is too different from Dick’s novel for you to accept this entry, Denis Villeneuve’s sensational sequel, Blade Runner 2949, ensures that more of the source material is included in this followup (we can’t complain with two terrific adaptations, can we?).

I'm Thinking of Ending Things

Charlie Kaufman has adapted a novel into a film before, but Adaptation. is kind of the opposite of what I’m looking for here (he took Susan Orlean’s The Orchid Thief — an adaptable novel — and turned it into an impossible adaptation). What makes a bit more sense is to include his version of Iain Reid’s haunting, meta novel I’m Thinking of Ending Things. While truer to its source material than Adaptation., Kaufman still takes a few liberties with I’m Thinking of Ending Things yet he still captures the novel’s sense that we are trapped within the confines of a distraught, meandering mind. Perhaps as a flex of his own, Kaufman released his novel Antkind around the same time with the sole intention of writing a book that would be impossible to turn into a feature film; we’ll see if that remains true.

Inherent Vice

I didn’t understand or love Paul Thomas Anderson’s Inherent Vice until I finally got around to reading my first Thomas Pynchon novel (in case you’re interested, it was The Crying of Lot 49, which is digestible enough due to its short page count for any newcomer to his novels). I finally understood Anderson’s approach from that point on. His adaptation of Pynchon’s noir novel perfectly represents the author’s frantic form of storytelling that loses the sense of plot in favour of digging as deeply into the psyche of his paranoid characters as possible. If you try to focus too much on what is going on, you will feel just as lost as the people in Pynchon’s novels. Should you be swept away for the ride, you’ll discover qualities of the human experience that not many other novels or films can grant you.

Life of Pi

Yann Martel’s novel, Life of Pi, was often considered too tricky to adapt into a film given its large scaled forms of philosophy, minimalist design, and its spiritual connection with the reader. Ang Lee is a director that loves taking on any new risks, and sometimes they work better than others. One of his greatest achievements is how seemingly effortlessly he brings Martel’s story to the big screen with Life of Pi: a cinematic experience as rich as can be. With some of the best 3-D I’ve ever seen in a theatre, Lee made sure that his film leaps off the screen just like Martel’s words do. Occasionally surreal and truthfully ambient, Lee pulled off the impossible with his acclaimed film which he naturally won Best Director at the Academy Awards for.

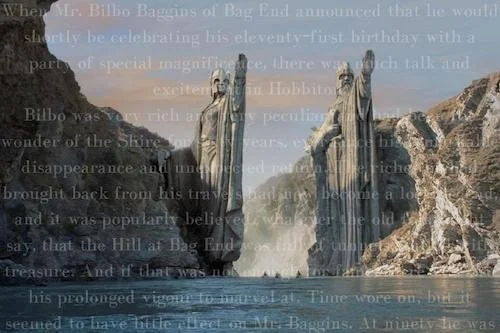

The Lord of the Rings Trilogy

Peter Jackson is far from the first or the last person to try and take on J. R. R. Tolkien’s texts, but he may be the only filmmaker to actually do his novels justice. His version of the Lord of the Rings trilogy is as epic and ambitious as Tolkien’s writing. Although there are a few liberties taken (I think excluding Tom Bombadil from the films was for the best, for instance), Jackson mostly translates the scale and scope of the novels to the big screen with some of the greatest fantasy films ever created. To prove how miraculous this is, Jackson’s efforts with The Hobbit weren’t even remotely as successful (mostly due to studio meddling, mind you), and Amazon’s prequel television series is quite a chore in comparison.

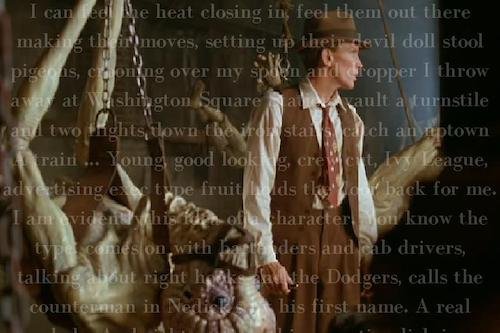

Naked Lunch

Okay, so maybe William S. Burroughs’ Naked Lunch is impossible to adapt, given its fragmented, nonsensical nature (and also how insanely problematic it is with a modern lens); this is because Burroughs was experiencing his own battles with heroin addiction for a good portion of his life. Well, if there was ever a noble attempt at adapting such a novel, David Cronenberg delivered it with his filmic version. Instead of trying to adapt this book directly, Cronenberg instead makes his Naked Lunch a take on how such a novel could have even been conceptualized whilst staying true to some of the events, characters, and settings of the novel. Cronenberg’s film is far more straightforward, but at least the hostile, nihilistic tone of Burroughs’ classic remains.

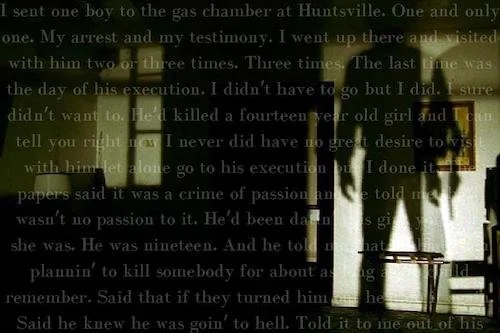

No Country for Old Men

The works of Cormac McCarthy have been adapted time and time again, but the one time that any film has conveyed the late author’s tone and density perfectly (or even better) is when the Coen brothers took on No Country for Old Men. Replicating the bleakness, existential dread, and visceral gore of the source material, the Coens represent the gothic south with this neo-western opus: a cat-and-mouse chase through the grotesque, criminal underworld of America. They even cap off their feature film as bluntly as possible: only a move McCarthy would implore others to use. Not only was the adaptation a success, but the film itself has gone down as a modern classic, sweeping up many Academy Awards (including Best Picture) and other accolades to boot.

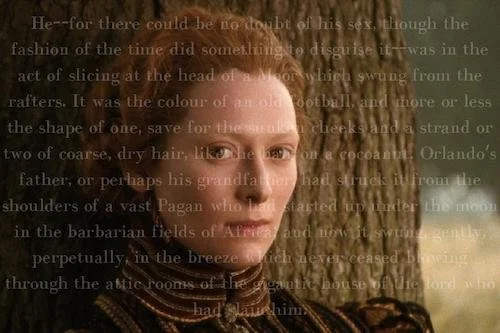

Orlando

Virginia Woolf’s stream-of-consciousness style of writing may not make any literal sense when applied to the cinematic language, but Sally Potter’s Orlando is as close as we’re going to get. Streamlining Woolf’s multi-generational, surreal “biography” of the titular protagonist (who even changes genders throughout the story), Potter’s Orlando takes us on an epic journey through time and consciousness. While it doesn’t maintain Woolf’s otherworldliness in quite a literal way, it does a great enough job while remaining a thorough, sensational feature film in its own right; I feel like any more exploration would have resulted in a weaker film, but Potter knows exactly how much of Woolf’s text to take on directly.

The Trial

We conclude with Franz Kafka’s absurdist opus, The Trial: one that wasn’t even properly finished before the author’s abrupt demise. The story covers the tribulations of Josef K. who has been arrested and tried for a crime he didn’t commit (or even know about, and neither does the reader whilst venturing forth). Orson Welles clearly thought adapting the works of William Shakespeare was a cakewalk when he opted to cover this novel instead, resulting in a trippy, anxious, delirious feature film aided by Edmond Richard’s incredible cinematography (which heightens the claustrophobia of the source material). Dismissed when released, Welles’ film — which he considered his personal very best — is now beloved by cinephiles: he apparently saw something then-contemporary audiences missed.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.