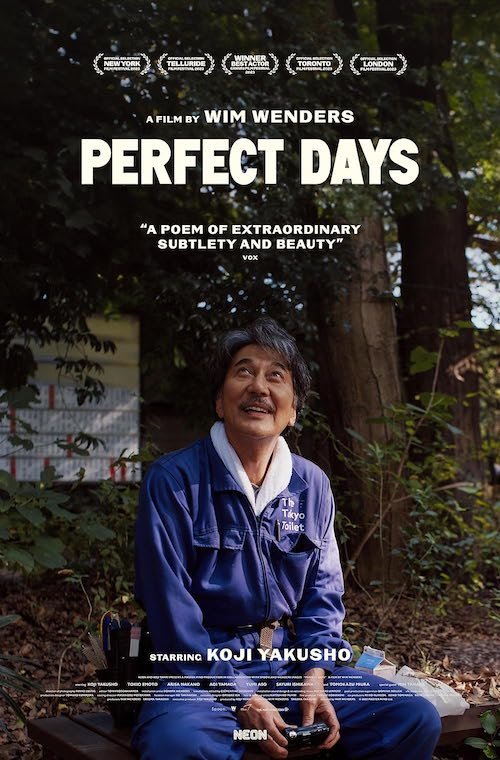

Perfect Days

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Wim Wenders has to be one of the most hit-or-miss directors I know. His weaker films feel like absolute chores to crawl through. When he wins (and he does so often), however, he creates masterworks that transcend language and global barriers. He has a knack for planting himself wherever in the world he desires and making something substantial with the culture, history, and customs of where he has landed up. Additionally, he has something important to say artistically in these excursions. At his best, Wenders allows you to travel the world and learn new things, both from your surroundings or within yourself as a person. When Japan submitted his latest narrative film, Perfect Days, to represent the nation at the Academy Awards for the Best International Feature Film category, it was the first time in history that a non-Japanese filmmaker was chosen to be the face of the country. That’s not to say that Japan had bad films last year, not with some triumphs like The Boy and the Heron and Monster. I feel like there was an agreement on how Wenders encompassed life in Japan in his humble, gorgeous, meditative feature Perfect Days. In short, Wenders has done it again.

While Wenders had help writing for his Japanese cast with co-screenwriter Takuma Takasaki (who also was a part of the team of producers), the best choice made to make Perfect Days speak directly to its Japanese audience was the casting of Kōji Yakusho: a veteran actor of the nation who may never be better than he is here. Sure, he’s been in beloved works like the Palme d’Or winner The Eel, Oscar darling Babel, and many favourites for numerous walks of life (13 Assassins, Memoirs of a Geisha, Mirai, take your pick). That’s why he was selected: because we’ve seen this familiar face many times before. Here, he represents everybody. He is Hirayama: a cleaner of public toilets for the city of Tokyo. He tries to maintain composure and optimism in a reality where he is cleaning human waste and mess for a living. He finds solace in music and literature. He dreams in black-and-white (his visions are abstract, claustrophobic, and indicative of how trapped his ambitious imagination is: his potential is wasted on a life that he never asked for). He just wants to get by. Is that so much to ask? Perfect Days presents us with his usual routines and the curveballs that are going to bring him back down to the ground to face the reality that he’s unhappy with the state of his life. We’ve all had these moments, right? We’re doing what we can to survive and save face until we cannot ignore the reality of the state of things, even if for a little while. Perfect Days is all about these confrontations.

Perfect Days forces us to face both the things in life that challenge us, as well as whatever brings us peace.

Yakusho never demands the space of any shot, but his internal conflicts command the screen in every sequence he is a part of (which, essentially, is all of them). He aims to get by no matter what, but Perfect Days proceeds to keep testing him; not just his patience, but his empathy, self-reflection, and even his wellbeing. The ending of the film discusses the concept of komorebi: the Japanese word for the sunbeams that filter through the leaves of trees and create a calming effect of peace and visual splendour for split seconds. Perfect Days is all about finding the shreds of hope and joy in the dismal, the depressing, and the shadows. Wenders, Takasaki, and Yakusho all take this mentality to heart with Perfect Days: an examination of the little it takes to break us, but, in that same breath, how little it takes for us to make the most of life no matter what we do. We start the film off by being acquainted with Yakusho’s Hirayama and his toilet-cleaning job. By the end of the film, we know someone else completely: a fully-fledged human who deserves to be loved and have a better life than this. Once we share a teary-eyed car ride together (a stilly framed shot of Yakusho that results in the best few minutes of acting in his whole filmography and, perchance, of any actor in 2023), we know the crux of what Perfect Days is all about: finding release in those that live by hanging on whilst encouraging them to keep going. We love them no matter what they do for a living.

Stylistically, Wenders tips his hat to numerous Asian auteurs; he captures the domestic spirituality of Yasujirō Ozu, the neon fever dream nostalgia of Wong Kar-wai and the glacial stillness of Apichatpong Weerasethakul. Together, we get a reverie about one who aspires for more in life; we daydream the daydreamer. The diegetic music throughout Perfect Days acts as the heart of the film, and there’s a killer playlist to help Hirayama get through life (and us through the film), ranging from cuts by The Kinks and Patti Smith, to some deeply personal selections. Of all of the Lou Reed and The Velvet Underground choices, the multiple uses of the former musician’s “Perfect Day” (hence the name of the film) is utilized with the tune’s bittersweetness in mind, especially to close out the film via an instrumental melody during the credits. A cover of The Animals’ “House of the Rising Sun” may be one of the most emotional takes on the song you’ll ever hear as the words of another somehow bring out the pains of one’s heart over a late-night open mic session. Finally, there’s the song that consoles us the most: Nina Simone’s version of “Feeling Good” (an overused song that is still utilized sublimely and properly here), presented as an anthem of catharsis.

Perfect Days is about those who are dead on the inside, yet it is depicted with such life and passion.

Many directors have focused on the soul-crushing ways of life for many, and Perfect Days technically is no different. However, Wenders vows to depict the soulless with as much life and love as possible in what is truly a beautiful paradox of a film. In the real world, this character may not mean anything to anyone. Yet he is a superstar in our eyes, because of the filmic podium he is granted. Whether you consider this film a series of shorts or vignettes that happen in one man’s life or a flow of anything and everything that he faces being only connected through a protagonistic vessel, Perfect Days still reads like a slice-of-life feature that introduces us to a lonely, aching soul and what keeps him ticking. I guarantee we all have those things that make us want to keep going. In case it isn’t obvious via this very article you’re reading, I strive to discover more films I adore (amongst many other things that make me want to keep living life to the fullest). Wenders’ goal with this film may have been to remind you to do the same, but he has actually helped you achieve it in the same project. Perfect Days is one of those films I adore. I’ve found another one. It’s magnificent works like this that keep me so in love with cinema. Film, in and of itself, helps me cherish life. Perfect Days is undeniably Wenders’ best narrative film in decades (so excluding his sensational documentary work, including his other 2023 release, Anselm), and it is a feature that you can truly describe in one word: special.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.