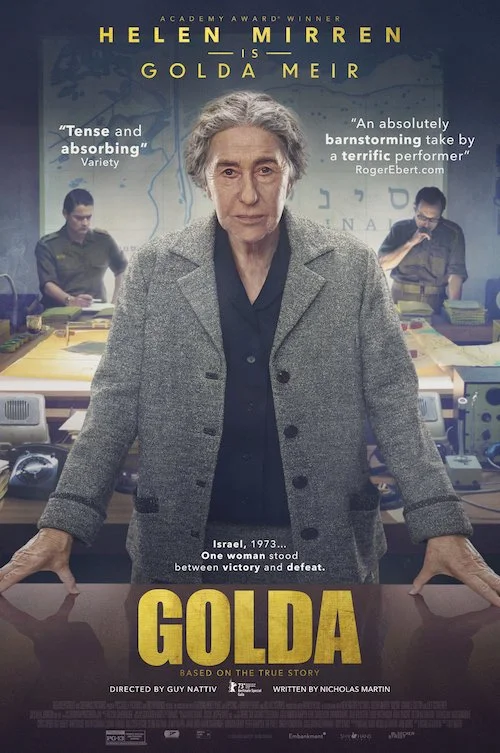

Golda

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Guy Nattiv made waves when his short film Skin won an Academy Award back in 2019, and a film of his is possibly returning to the Oscars discussion. Enter Golda: the historical drama that may be a lock for Best Makeup & Hairstyling this year, all thanks to the work that renders Dame Helen Mirren all but unrecognizable (her wrinkles, cheeks, and other identifiable traits shift from scene to scene, however). Outside of that loose comparison (that two works by Nattiv are attached to the Academy Awards), there’s not much common ground here; Skin makes the most of its short run time via creative storytelling and showing only what is necessary, and Golda felt too long once it got to the ten-minute mark. This take on Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir is sadly so fixated on what techniques and devices would make it an awards season darling that it becomes a dull task to watch. Many scenes feel the same. A lot is going on and yet it doesn’t seem like it. Even Nattiv has a few interesting choices that get cancelled out by the plethora of typical tropes that he also includes. I’m hoping not to come across as too harsh regarding Golda as there were clearly good intentions that went into making this feature, but one of my least favourite kinds of films are Oscar-bait works that crawl along slower than a snail’s pace and arrive exactly where the previous ten thousand other films did. Golda is one such film; not the first, and not the last.

The film takes place during the Yom Kippur War of 1973 between Israel and Arabian nations Egypt and Syria, lasting from October 6th to 25th (its name comes from the first day of the war when the Arab coalition executed a sneak attack during Yom Kippur). Meir is initially warned of this surprise attack in advance via intelligence, but she dismisses the information as she didn’t have the time or conclusive approval to strategize a counterattack in time. Post-attack, we count down the twenty or so days of Meir’s choices and the deliberation required to make them. All well and good, but we never really learn much about Meir as a person, outside of her chainsmoking habit, her personality (which, in my opinion, feels more akin to this story than the real Meir herself), and the only other subplot found in this painfully thin narrative: Meir is suffering from lymphoma, which most certainly affects her decision making. What we get instead of a full depiction of The Iron Lady of Israeli Politics is a bunch of yes-or-no choices in closed-off locations. This would be a cakewalk for someone like Aaron Sorkin who purposefully confined his settings and amounts of characters in something like Steve Jobs as a challenge for himself, but Golda feels frustratingly hollow instead. This film reads like an archived chat log of a Dungeons & Dragons-styled discussion based on this particular war (particularly all of the questions and decision-making), and that is not a good comparison to have.

This wouldn’t be the first time that Helen Mirren has saved a film from being completely unwatchable.

What keeps this film even remotely interesting and full of life is Dame Helen Mirren starring as Meir, and her performance does make a character — who otherwise feels like a talking head — feel real. Even when the makeup work, which is usually pretty strong, shows its flaws (the moments when her cheeks droop destroy the illusion a little bit, for instance), Mirren is there delivering one of her strongest performances in recent memory (but it’s Dame Helen Mirren we’re talking about, so it’s far from the best acting she’s ever done). I was only drawn in because I wanted to know what would happen next regarding Mirren as Meir. That’s it. Otherwise, Golda feels like a series of missed opportunities. If we’re going to spend an hour and forty minutes with Golda Meir, we should feel like we’ve actually spent that time with her. Instead, Golda plays like a high school production with established actors; that doesn’t save the vapidness of what should have been a thorough analysis on an important time in history.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.