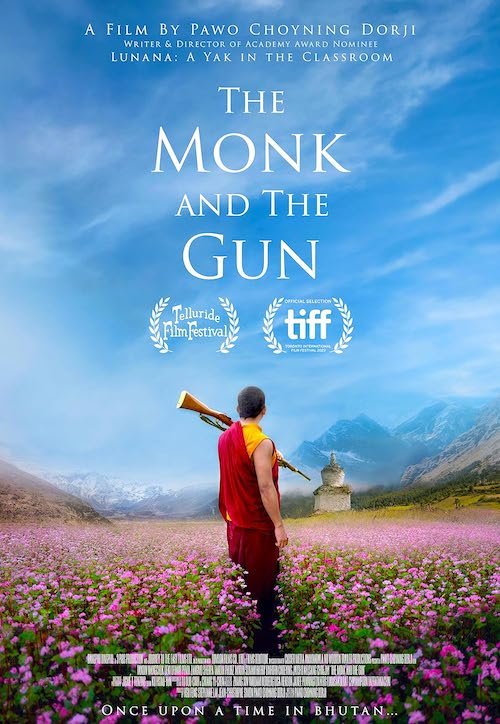

The Monk and the Gun

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Two-thirds into The Monk and the Gun, a line is delivered that emphasizes that many countries on Earth are eager to experience the changes that Bhutan is experiencing and that all should feel lucky (not in so many words). This comes over an hour after the opening sequence that depicts Bhutan on the cusp of becoming a new democracy in 2006, and so a mock election is to be held; the line is given by one of the people in charge of the election. As the film progresses, the days leading to the election are determined by how many phases are left before there is a full moon. The Buddha was born during a full moon, so believes Buddhists (whose religion/beliefs are crucial in this film), so it feels like The Monk and the Gun is building towards something else: rebirth, perhaps? This is just the backstory of something much more succinct in the latest film by Pawo Choyning Dorji, whose debut film, Lunana: A Yak in the Classroom, was one of the biggest surprise Oscar nominees in recent memory (needless to say the world was introduced to a gorgeous film that they wouldn’t have seen otherwise, so no complaints here). That felt like a small vision. The Monk and the Gun is a bit more ambitious in what it is trying to say about Bhutan, shifting viewpoints, and the state of the world.

At the forefront is a tale of a lama that notices the mock election is to take place — one that acknowledges the reign of the fifth Druk Gyalpo, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, since December 2006, and its official first election in 2008 — and has something to say about it. He instantly asks a monk to find him two guns, and the latter obeys and goes in search of any weapon (they are evidently hard to come by). As this goes on, there is a slew of outside influence that seeps into the town of Ura, including the hype surrounding a then-brand new James Bond, played by Daniel Craid, in Casino Royale. That obsession with action and gunplay is quickly contrasted by the plot thread involving an American tourist in search of an antique rifle; his quest leads him to a farmer who possesses it. Since the nearest bank is so far away, the tourist — who is willing to pay tens of thousands for this artifact — promises to come back with the promised money the next day, leaving enough time for the wandering monk to find this very rifle to bring to his lama. The tourist is clearly flabbergasted, and thus begins his best efforts to score this rifle back; all while Ura is beginning to wonder what a democracy entails, and what shifts will be coming to the civilians’ way. It’s these very shifts in culture, society, politics, and leadership that get questioned throughout the film, the same one that has to reemphasize that many nations don’t get these kinds of progressions (and the same film that acknowledges that there are also countries that don’t like how they do change, and I think the inclusion of an American tourist seeking out weapons is intentional for this very reason).

The symbolism in The Monk and the Gun is profound enough to intrigue you right away and leave you thinking after the ending credits roll.

The different storylines all converge into one rush of a film: one where you are worried about where all of this is heading. This is the same director of Lunana. Surely The Monk and the Gun won’t dip into peril or gruesome territory, right? It certainly looks like it is focusing on the inherent evils of humanity for the most part, but that’s the secret to The Monk and the Gun: a film that makes it clear that it’s not too late to have a change of heart. If we can try to change an entire nation’s politics and pop culture, we can also change ourselves. This is when the Buddhist philosophy kicks in: a cleansing of self and becoming free of sin and ill-thought. Yes. The Monk and the Gun is just as beautiful as Lunana, albeit in a different way. This time, we’re not looking at filmic art as-is. We’re asked to have faith in Pawo Choying Dorji and this film to guide us through what looks to be treacherous, dooming territory. This is an actual journey, not a mindset. The Monk and the Gun invites you to have a journey within yourself, within Bhutan, and within the zeitgeist of the twenty-first century right before the world became the ball of rage we now know it. We’re all capable of becoming better, even if all the signs point to us being destined for evil.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.