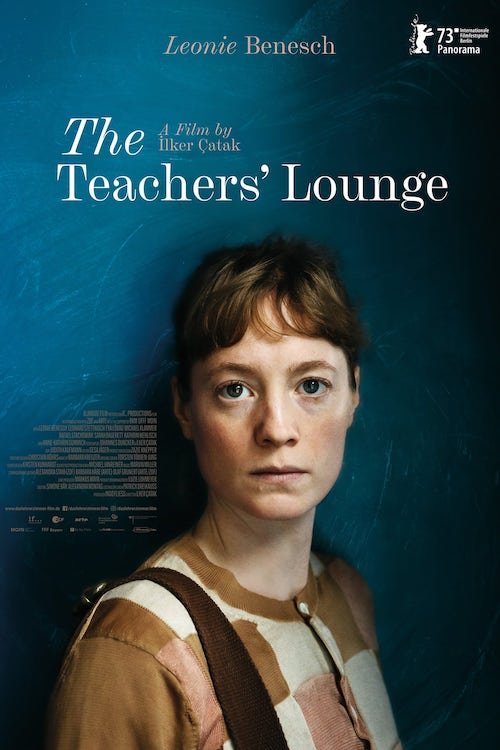

The Teachers' Lounge

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

If you think Hollywood has a problem likening the lives of children to those of adults without being pandering or flat-out illogical, look to the cinema of the world. Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation forces the kids of a broken home to wrestle with the dilemma of which parent they would rather be with despite the flaws of both guardians. Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth compares the wandering imagination of a child experiencing the Spanish Civil War to the actual bloodshed going on around her. The latest successful example is İlker Çatak’s phenomenal downward spiral known as The Teachers’ Lounge: a drama that pits kids against kids, adults against adults, and kids against adults. It sounds excessive, but let me assure you that Çatak’s film is an enthralling motion picture that unravels every bit as much as Farhadi’s magnum opus and forces children to answer to the decisions of adults like Del Toro’s masterpiece. Of course, a more seamless comparison to be made is with the Palme d’Or winning film The Class which similarly uses the education system to reflect on society; let me assure you that The Teachers’ Lounge is as good, if not better, which is saying a lot. A universally applicable take on mass hysteria, citizens rebelling against an oppressive and invasive government, and the vulnerability found within the school system, The Teachers’ Lounge handles friction with dazzling effect.

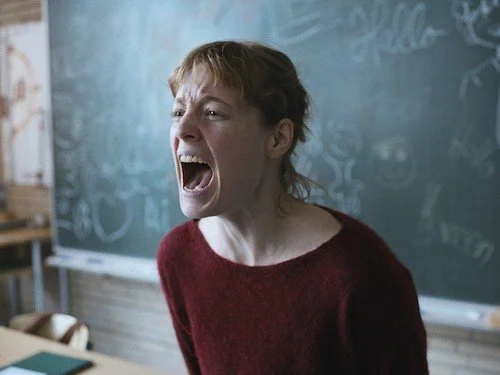

We kick off the film with the central character, teacher Carla Nowak (played by Leonie Benesch of The White Ribbon fame, yet another exemplary take on the lives of children versus adults). Carla insists that there have been thefts happening in the elementary school where she works, so she takes matters into her own hands by setting up surveillance to catch the culprit in the act. Initially, a student is suspected of these crimes, but Carla’s footage leads her to believe that an adult (nay, a cohort) may actually be responsible for her missing money. I won’t go any further, because the less you know about The Teachers’ Lounge, the better. As it unfurls its cards one by one, you’ll know that this is a splendid exposition of pacing, revelation of information, and thematic talking points. The direct comparisons between the classroom and the titular teachers’ lounge make the bridging between themes effortless. As Carla is finished teaching children for the day and is amongst her peers, you can see the clear thesis of this film: there really aren’t many differences between youths and adults when it comes to problem-solving and dealing with conflict. The line continues to blur more and more as the film continues. This bridge is necessary not just for the rivalries that develop but also for any possible resolution. Teachers aim to not just educate but to understand those they are instructing. The Teachers’ Lounge doesn’t forget this vital fact of the best educators and uses it as a shred of hope in a film full of despair and discord.

The Teachers’ Lounge is an excellent example of friction on screen.

At times, The Teachers’ Lounge feels like Alexander Payne’s Election (one of the very few Hollywood films to get the similarities between children and adults so accurately), only without the satire or cheeky side. The use of student committees and having them equate to the news and bureaucracy is not just clever: it solidifies the film as a strong allegory of how ill-prepared many positions of power are in this world, and how major decisions are made via wrongful information or floundering panic. The school itself functions as a symbol of society, and watching what was once an established system turn into unfamiliar chaos hits all the above points home. Still, there is a prayer for order that Çatak and the film have from the new generations, and they put this notion forward by punctuating a film about disarray with a sign that things — and people — can change; there’s an additional anecdote that also hints at the opposite (that society can keep going around in circles regarding its abuse of power). The Teachers’ Lounge is a thrilling essay on the imbalances of society and the call that we must — and can — do better in order to win against a poorly constructed system that has needed fixing for many years now (but, again, will society ever learn?).

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.