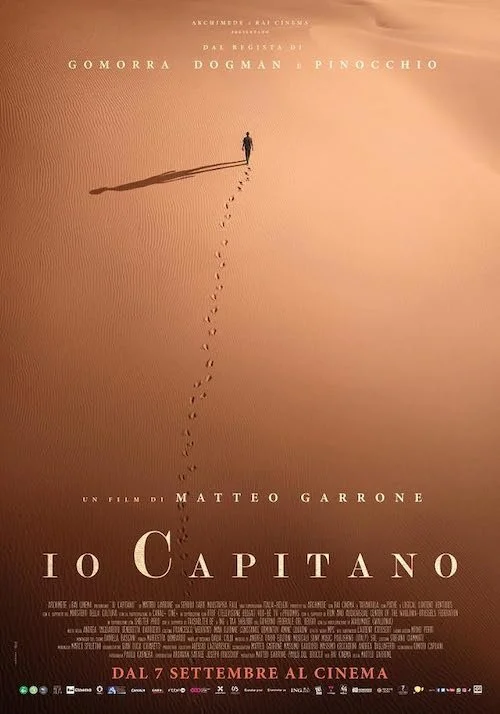

Io capitano

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

What does it take for dreams to come true? The Golden Age of Hollywood (or pretty much most of Hollywood’s history) paints aspirations as achievable conquests if one tries hard enough, but we civilians of the real world often recognize the futility in such fairy tales. Some features go to the opposite end of the spectrum and detail life as the challenging series of tribulations that it is for the majority of people. This is what Matteo Garrone’s Io capitano resembles: the kind of film that dispels the notion that one’s goals are dreams. To me, both are very different things: goals are what you set for yourself to push you towards a deadline or the next step, while a dream is a hypothetical that you wish would happen. Io capitano has two dreamers in the form of Senegalese teens Seydou and Moussa, who are a part of a deeply impoverished block in Dakar. They feel the need to leave their town and find a new way of life elsewhere, perhaps in Europe (Italy, specifically). They smile as they are excited for how their lives will end, but they have no idea how difficult the road ahead will be. Io capitano is aware of dreams, and it is also keen on giving dreamers a reality check: an unfair world will always remain unfair, no matter what you choose to do today.

I’ve seen comparisons to Homer’s The Odyssey when reading about Io capitano, but to me, this film is a flat-out homage to John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath: a similar tale where a struggling family travels in search of a better life, only to find that the grass is most certainly not greener on the other side (or at any other point along the way). While Steinbeck’s acclaimed novel is nothing to sneeze at (it is an American classic, after all), it details the morale and state of a nation during the Great Depression. Io capitano is larger in scale, as it provides the distress of multiple countries — nay, continents — as Seydou and Moussa are subjected to starvation, torture, and numerous other struggles as they strive for a happier life. In the two hours that Io capitano plays, you can feel the length of this trek and the weight of all that transpires within it. It’s certainly not an easy film to watch, but it is one to embrace, to understand at least some of the problems many face in parts of Africa and Europe even to this day (Io capitano is representative of the immigration experience of many regardless of their motherland and target destinations, mind you).

Io capitano understands the exhaustion of the journey present throughout the film, and it consoles its protagonists while they flounder.

As harrowing as the film is, I can’t help but feel an iota of love that is present throughout for its protagonists: an invisible, guardian angel that is helping these poor teenagers through all of the hell that they face. Given their faith, it’s clear that Seydou and Moussa give thanks to Allah as they travel, but I think Io capitano allows for you — those who feel like they are going through the motions in life as well — to feel this blessing however you see fit. There are also glimpses of fantasy elements that help these feelings of divine protection come to fruition. I also don’t think Io capitano gets cheesy or safe either. Any semblance of faith is small in dose and/or short-lived, and it usually is found in the humanity within Seydou and Moussa (oftentimes, they aim to act as the voice of reason for others). Even so, Io capitano is a heavy endeavour: an adventure that doesn’t waste a second to reiterate the severity of each stretch of the trip and the importance of all of this to work out. At the end of it all is openness: does all of this work out? Was it worth it? We’ll never know, as Garrone invites us to dream for the dreamers. We'd like to think that all will be okay for our two leads after all that they’ve been through, but we can’t be so sure, either. I’ll leave that for you to decide as well; all I know is that Io capitano puts these youths through enough, and perhaps the unknown is more comforting than the abrasive truth.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.