Robot Dreams

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Warning: This review may contain minor spoilers for Robot Dreams. Reader discretion is advised.

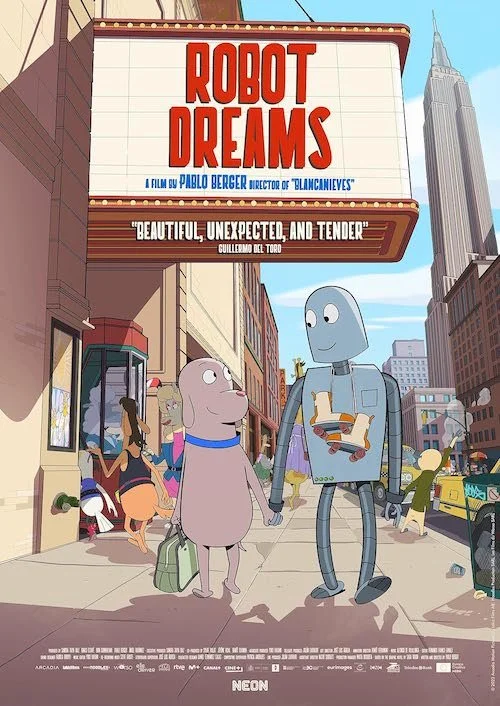

Perhaps one of the biggest surprises of the 96th Academy Awards’ nominations is a humble little animated film that crept its way into the Best Animated Feature Film category above some studio and distributor juggernauts (Disney’s Wish, Aardman Animation and Netflix’s Chicken Run: Dawn of the Nugget, Nickelodeon and Paramount’s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem). Instead, the Academy voters — and the rest of the world — were graced with Arcadia Motion Pictures’ Robot Dreams, directed by Pablo Berger (known for his live-action genre experiments like the modern silent film Blancanieves). We’ve got another bold take on a style here with an animated film that has zero form of recognizable dialogue in it; this isn’t exactly new territory, but Berger’s film is close to two full hours. Not once did I check my watch, regardless of all of these qualities to consider. I was transfixed by a world full of so many small details, populated by animals who all have their own interesting ways of getting by (yet they typically abide by the same anthropomorphic principles). This wasn’t just an animated world: this felt like a two-dimensional reality that we channel into.

Robot Dreams sets a very identifiable stage, despite how much this feels like a universe that isn’t exactly our own. We are planted in New York City in the eighties (there’s a notion of nostalgia within a hectic city life, here). Our first protagonist of two is a dog who is skittish and lonely. While flipping through channels one night, the dog finds an advertisement for one’s own robot. The dog doesn’t hesitate to make a brand new friend, and the robot comes to life after some assembly work and troubleshooting (naturally, the robot becomes the other lead character). It’s worth noting the personal connection we instantly have with both character concepts; dogs are often considered a human’s best friend (when wild canines were once domesticated for hunting eons ago), while we are slowly developing relationships with artificial intelligence these past few decades (Robot Dreams taking place forty years ago helps separate it from the fears of AI we presently have). Together, we see two different takes on friendship: a species of animal that humans programmed to be pals and parts that are Frankensteined together to make a digital being that we similarly program for our personal gain.

Robot Dreams is a bittersweet film that reminds you why you love those closest to you in life.

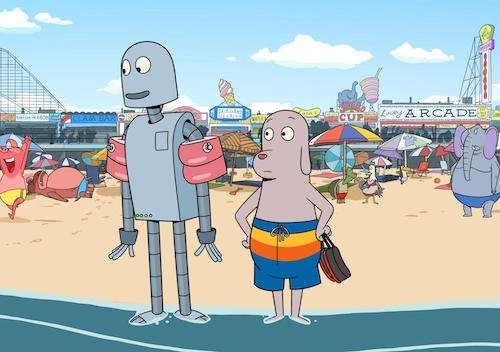

Naturally, the dog and the robot have an instant bond, as they enjoy a day out in the hot sun and experience many adventures together. They wind up at Coney Island for their next excursion, when the robot begins to rust and short circuit after taking a dip in the ocean. The robot is still alive but is unable to move (if it wasn’t short-circuiting, it most certainly was running low on batter after the hours of fun it just had), and the dog cannot carry the robot back home. The dog intends on coming back the next day with tools and how-to books so the robot can be fixed and these two best buds can have more fun.

Life doesn’t work that way, sadly. Robot Dreams proceeds to become a series of obstacles that get in the way of this mission. It feels like things will work out in some way or another until it becomes abundantly clear how much time has passed (and the labyrinth to get to where we want somehow grows, enveloping us in what feel like insurmountable tasks). True to the name of the film, Robot Dreams dips into the subconscious as aspirations for resolutions permeate the film. These act like vignettes that have their own fascinating properties for existing like a series of short films within this feature, united by the theme that one must snap back to reality and face the present. It becomes clear what Berger is trying to say roughly two-thirds in: that we must be okay with the inevitable. All we can do is be happy for those we care about, regardless of the state of things. I’m trying to be purposefully vague because Robot Dreams feels like a special event to watch, and the less you know going in, the better.

It takes a lot to connect with audiences by telling them next to nothing and showing them everything. It seems easier said than done to proclaim that cinema is a visual medium and so a dialogue-free film should work just fine. I’ve seen films with dialogue completely fail at trying to deliver themes, ideas, or even basic passages of story. Robot Dreams manages to drill right into your heart and deracinate the indescribable feelings we have, fully present them on screen, and make them understandable for us to relate to. What a tall order this is. Again, I’m used to many films not knowing how to relay basic information, and Robot Dreams is able to put a face to the emotional grey area that I can’t quite figure out on my own. Is this joy, sadness, regret, or love? Robot Dreams lets us know that it’s all of the above.

What a special, lovely, sweet, tragic little film Robot Dreams is. It possesses so much imagination that the film is full of heart and love despite its themes of societal alienation and existentialism (as well as the hostility of those whom you don’t connect with). Due to the use of animals and the occasional use of depressing subject matter to get humanistic points across, I couldn’t help but think of the tragicomic series BoJack Horseman while watching Robot Dreams, particularly the line that the character Diane Nguyen delivers about how life feels like a puzzle assembled from varying puzzle pieces from different sets until you realize that you are the piece that “doesn’t quite fit”. Robot Dreams is all about the quest to find one’s place in society and hoping that the piece you once interlocked with also fits in the final puzzle you were meant to be associated with. It doesn’t always work out that way. All you can do is hope that your loved one fits in a puzzle of any variety (and let luck dictate whether it’s the same puzzle as yours or not). As viewers, we get our hearts set on both parties and pray for the best. We don’t always get what we want in life. Sometimes we do, just not quite how we expect it. Robot Dreams is about accepting life as a unified experience we all share, as well as lives as individual concepts and experiences. It is tenderly gorgeous, and I was left drying my eyes once or twice; a film about a dog and a robot made me reassess the human experience (funny how that works).

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.