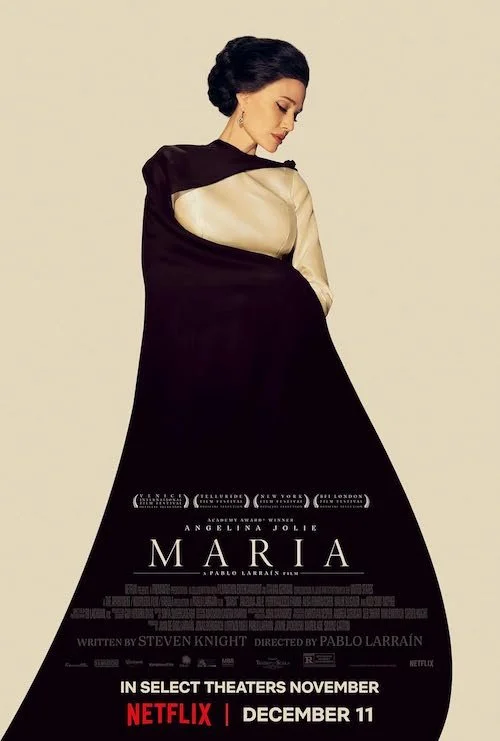

Maria

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

One of my favourite films of all time is The Double Life of Veronique by Krzysztof Kieślowski. This film — which deals with the contrasts made between life and death, amongst other parallels — kicks off with star Irène Jacob (as Weronika, in this instance, seeing as she also stars as Véronique) singing outside with the rest of her choir. Once it begins to pour with rain, the other singers leave, and Weronika stands alone (now sounding like an opera singer defending herself against the elements); her final note rings for what feels like an eternity. She was meant to sing until the bitter end. This preempts the rest of her storyline: a swansong waiting to happen at any given moment.

Pablo Larraín preludes his final film of his loose trilogy of fables (which involves celebrated women of the twentieth century and their struggles and triumphs via arthouse-esque, psychological backdrops) with the death of Greek opera icon Maria Callas. In his other similar films (2016’s Jackie, about a grieving and traumatized Jacqueline Kennedy, and 2021’s Spencer, about Princess Diana’s mental and biological suffering during a particularly tumultuous holiday season), we walk through the darkness with these women and anticipate the light at the end of the tunnel ahead. We know that none of these three women make it through to the new millennium, but we wish them all the best during these distressing times nonetheless. Maria is the outlier: the only film of the three to address that the darkness won via Callas’ passing, after a lengthy battle with the world (media scrutiny and obsession) and herself (the loss of her brilliant voice, and her plummeting weight). However, death is what makes us appreciate and understand life, so Maria then flashes back a week prior to Callas’ departure, and we spend seven days with a tortured soul knowing what the outcome is. The twist is: she knows she’ll be dead at any given point as well. She anticipates it.

I bring up The Double Life of Veronique not as a pale observation but because I believe Maria is fully inspired by it. From the use of opera and classical singing to convey an angelic voice as the cherishing of life and anticipation of death, to legendary cinematographer Edward Lachman’s use of the colours green, brown, and amber (a distinct colour palette that can only stem from Kieślowski’s masterpiece), it is clear that Larraín found solace in this film specifically when channeling Callas’ final days. Why? I assume it’s because he wanted to convey the double life of Maria Callas: the opera superstar, and the trapped songbird who could never leave her cage behind closed doors. Throughout the film, we see Callas and those around her bring up her two personalities (like there are two similarly named protagonists in Veronique). There’s Maria (who the film is named after), who is the Maria Callas at home. Then, there is “La Callas” or “La Divina” (the latter being a nickname she had, meaning “The Divine One”): the powerhouse vocalist. Not only does Callas chase after this honour again, but others expect if of her (as she trains her vocals throughout the film, she is told that “La Callas” was briefly in the room during a session, meaning there are hints of greatness but much work to do).

I’ve seen other critics bring up how they wish Maria went deeper into her story, but I feel like we get enough information to understand that Callas was forever forced to sing for others to the point that she never felt like her voice was her own; she just wanted to be able to sing for herself, just once. I don’t think we need to see Callas be punished when her mental and physical state towards the end of her life is heartbreaking enough. That’s the final comparison I can make between Maria and Veronique: the use of empty narrative spaces to allow your empathy to swell to the point of eruption. Thus, Maria feels like an operatic tragedy: one where you may not speak all of the words of the sung language, but you feel every ounce of what they mean. With less exposition and more room for interpretation, when you watch Callas sing, it’s as if she is telling you everything that is on her mind and in her soul right there on that stage; to me, that’s enough to go by. I know this method works, because it only took around twenty minutes (when Callas’ first on-screen song takes place) for me to want to fight back tears; my heart broke for her despite not even knowing what was being sung (I could still feel her message, no matter the language).

Maria is a fragmented story that takes place within an equally broken mind.

As previously mentioned, the most of what we see are variations of brown, green, and amber. I feel like we’re watching gold shine through rust and oxidation. Callas isn’t what she once was, but she still has the raw talent necessary to lift our spirits. However, Maria is about her time. The film is shattered from the jump, as we are made aware of Callas’ psychological state almost instantly; we see Callas (Angelina Jolie) taking too many pills which causes her to hallucinate, all while not eating as an effort to lose weight and not look like a “frog”. She resides in Paris with her help (but otherwise alone), feeling trapped within her domicile. She envisions an interviewer (Kodi Smit-McPhee) following her around to make a film about her life (which, in return, feels like meta commentary from Larraín, who seemingly admits to not knowing how to encapsulate the legacy of a titan within one teensy film); no one else in the film seems to notice this interview taking place, but her helpers — butler Ferruccio (Pierfrancesco Favino) and maid Bruna (Alba Rohrwacher) — seem to already know about her delusions and are prepared to help Callas at any instance (even if they’re unsure of how to best approach each situation).

Meanwhile, Callas continuously sees a concert pianist to practice her singing again after years of vocal deterioration. She sifts into the past with each performance, as she reminisces her younger self in full costume and makeup with adoring audiences ready to erupt to their feet once she concludes. Whenever we cut back to the then-present, we see Callas fight to get notes out, and her eyes tell us that she is aware of her inability to hit these pitches deep down. When confronted with why she keeps trying to push herself to lengths that are no longer achievable, Callas declares that she wants to finally be able to sing for herself; and so she continues to strive. We get some hints of her reasons why she wants to reclaim her voice through greyscale flashbacks, including a young Callas being forced to sing for Nazi officers during the years of Axis-occupied Greece, and her affair with Aristotle Onassis (who forbade her from singing). Without getting into the depths of each scenario, it’s implied that Callas was abused or exploited by almost every single person who declared that they loved her; unlike some other critics, I’m grateful that Maria doesn’t drag her through this pain again. It’s hard enough seeing her body and mind betray her.

Callas’ final week is detailed through five parts: an intro, a three-act structure, and a final chapter titled “An Ending: Ascent,” which gave me Pavlovian whiplash. You see, Maria doesn’t have a big-name composer crafting breathtaking scores this time around (like Mica Levi and Jonny Greenwood’s music for Jackie and Spencer, respectively). The music of Callas’ career is used throughout the film, which both makes sense and fits nicely. The only use of music from outside of Callas’ discography is — as I had hoped — the umpteenth use of Brian Eno’s brilliant ambient classic, “An Ending (Ascent)”. While it isn’t quite as perfect of a match as it was in, say, Steven Soderbergh’s Traffic, there’s something both beautiful and eerie about hearing Eno’s song — which is chronologically and logically out of place, and yet it somehow sonically fits — segue us into the ending credits and on top of the found footage of the real Maria Callas gracing our screens. Eno’s song almost sounds like an operatic wail from the great beyond, as if Callas’ voice is still with us. The title of the track is most certainly true; it’s sad that Callas’ story had to end in order for her to finally be able to fly away freely.

Angelina Jolie delivers a career-best performance as Maria Callas in Maria.

Of course, it wouldn’t make sense to continue further without bringing up the woman of the hour that helped Maria be elevated to such extreme heights: Angelina Jolie. Jolie, who I have never overlooked as an actor and have always wanted better projects for given her talent, has never been better than she is here. After she had months of operatic training, the fact that Jolie can even reach the heights of a worsened Callas is phenomenal; it makes sense, given the emphasis of how unrefined Callas is now, to have someone who isn’t absolutely perfect at operatic singing take on this part. We mustn’t forget the parts where Jolie sings like a siren from the great beyond without a hitch, and you can sense every ounce of pain or glory from her eyes as she belts her heart out. If singing was the only prerequisite for good acting, Jolie would already be dynamite. Seeing as Jolie fully transforms, I’d easily consider this one of 2024’s great performances. While her brown contact lenses only take her part of the way through her shift (she could pass for Ingrid Thulin, should the Swedish star ever get her own biopic), Jolie’s commanding presence, hypnotic voice, and reserved-yet-emotional acting (not once does she have to chew scenery to try and appeal to Oscar voters) drive this illusion home. I was always closer to believing this could be Maria Callas more than I was reminded this is Angelina Jolie giving this role everything she has.

While Maria dips into the obscure a little more than Jackie and Spencer — which automatically makes it the weakest film of this trilogy (if barely, just because it doesn’t get into a synthesized, cohesive understanding of its subject quite as nicely as the other two films) — I do appreciate Pablo Larraín not holding back with this last entry specifically because of how unhinged it feels by comparison; there are benefits to this being the boldest of the three films. If one were to watch the entire triptych in one sitting, they’d find obvious parallels (the Onassis and Kennedy connections with Jackie, down to having the same actor from that film, Caspar Phillipson, return for Maria, as well as eating disorders like in Spencer). Jackie is far more visceral and rooted in reality; Spencer dips into Princess Diana’s mind enough that it becomes a sense of escapism for the late royal; Maria is almost entirely removed from reality. Jackie begins with life after the death of John F. Kennedy; Spencer feels like a brooding warning for what was to come to Princess Diana; Maria begins after Maria Callas’ demise. These three films are linked far more strongly than you may imagine on paper.

I understand that Maria won’t strike a chord with everybody given its alienating and aloof nature, but I personally found myself fighting back tears from very early on; we’re essentially watching a dying person use every last ounce of their being to regain a voice that they felt was never actually their own. Sure, the film doesn’t quite dive into the quirks and narcissism of Callas, but we get enough of her personality through Angelina Jolie’s sublime performance that the essence of Callas is there; how are we supposed to get the traditional, cliched biopic treatment from a narrative that takes place over seven days (and change, given the flashbacks)? Nonetheless, while we’re never truly sure of what is taking place given the state of Callas’ mind, we get Larraín’s depiction of her version of the story in Maria: a haunting, psychological prison of memories and delirium, where we wait for a tormented spirit to be released of her demons. Despite her death being what opens the film, it is only once we watch all of Maria and understand her passions and proverbial lesions that we know how she is set free. While highly unorthodox by the standards set in place for biographical pictures, I connected far more with Maria than I have with any similar film this year (and likely will, given that the kitschiest are on their way this awards season). To watch a basic biopic is to get the half-baked rundown of someone’s life; a film like Maria tethers us to Maria Callas’ spirit in ways a cookie-cutter release could never.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.