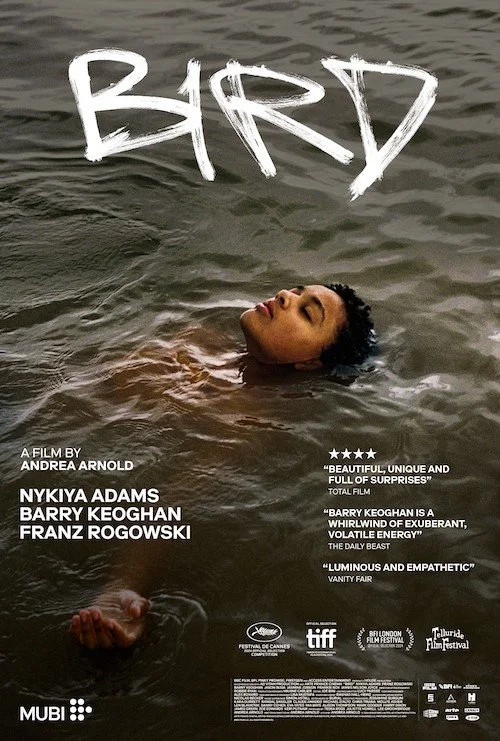

Bird

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

When I was an undergraduate student fourteen years ago, I took a screenwriting class at York University that showed us an example of a short film that embodied the brilliance of precise writing. That film was Andrea Arnold’s Academy-Award winning film, Wasp, from 2005. We follow a dysfunctional family consisting of a single mom and her four kids. They live in a destitute neighbourhood, and the mother — who is already stretched thin and unsure of how to better the lives of her loved ones — makes her seemingly umpteenth wrong decision and gets distracted with a guy she is interested in. In the span of twenty-five minutes, we understand the dynamics of this family and their living conditions, see growth or regression in these characters, and even have the breaking point that is punctuated by the appearance of the titular insect (which is cleverly integrated). Wasp catapulted Arnold’s career, and her opus, Fish Tank, was just around the corner in 2009. With a few films since, including the beloved American Honey in 2016, it’s safe to say that Arnold is one of the best directors of our time — next to Sean Baker (of Anora and The Florida Project fame) and the Dardenne brothers (the Palme d’Or juggernauts behind Two Days, One Night, L’Enfant, and Rosetta) — to depict the struggles of the lower and working classes.

Her latest film, Bird, continues this hyper-realistic look at impoverishment in the United Kingdom, but it does try something different and atypical for Arnold: a hint of magic realism. Without warning, Bird dips into some fantastical territory, and I will get into these elements later without explicitly discussing what these moments are; just that they exist. They happen in the mind (or not) of Bailey (Nykiya Adams): a twelve-year-old who lives in a disheveled block and unit with her younger sister, and her dad, “Bug” (Barry Keoghan). Bug plans on marrying a woman he barely knows, and the money for said union will be funded by the help of a frog (which, if memory serves correctly, is erroneously called a “toad” throughout). The frog can produce hallucinogenic slime under distressing conditions (or, in this case, apparently via the serenading of “dad rock”). Bailey doesn’t approve of any of this plan and refuses to partake in the wedding, despite being invited to be a bridesmaid. Her half-brother, Hunter (Jason Buda), is now a part of a violent gang who break into the homes of wrongdoers and attack them quite graphically.

There is an ongoing plot point that is quite major, and it begins with Bailey running away from home and waking up in the middle of a field. She is welcomed by horses, and then she notices a stranger in the distance. He is a mysterious man named Bird (Franz Rogowski) who is trying to find out who his parents are and where they have gone. At first, Bailey is defensive and wants nothing to do with him. She quickly finds comfort in his presence, maybe because he doesn’t antagonize or hurt her. After following Bird around for a short while, Bailey changes her tune and befriends him. It is through Bird that the fantasy elements of Bird, naturally, take place. I don’t want to go into them at all just because there aren’t many opportunities in the film for the magic realism to even take place, so I don’t want to spoil when or how they unfurl; I also don’t think they’re great.

Bird succeeds when it is rooted in reality. It never quite incorporates its magical elements well enough.

My main issue with Bird is that it feels like one completely different film with the dregs of another trying to strive for your attention and failing. Even with all of its world building and character construction, there feels like much is missing just because of the slight devotion to these surreal sequences or blips that never go anywhere. The very first usage of such a moment is briefly spectacular: a shot that you will wonder if your eyes deceived you or not (and, to be fair, this occurs past halfway into the film, so it’s easy to second guess yourself). If you spend a moment’s thought on what just happened, you begin to realize that it doesn’t quite make any sense; if redacted was able to redacted into a redacted before, couldn’t redacted just become a redacted whenever they see fit, and, as a result, not need redacted to complete their mission? Is this film just about the friends we make along the way in this hectic thing called life? This is the first sign of logic not being a part of the equation, and, sadly, this is the only surreal moment to actually even feel like it stems from the same film.

Every other magical moment (not that there are many, mind you) comes from out of nowhere, feels like they don’t fit in this film whatsoever, and as if they add very little to the overall experience (if the theme of Bird is that only miracles can pull a struggling child out of the hells of her life, the way the film goes about this idea is extremely flawed because these moments never feel earned or of the same story). You can argue that these magical moments are few and far between so that they shouldn’t affect Bird too greatly, right? Wrong. These sequences shape Bird enough to weaken some of the other story elements. We begin to question everything we see (and not necessarily in a good way), like are all of the birds we see throughout Bird lost human souls waiting to be found? If so, why don’t we get a bit more of this perspective? How is no one truly questioning the few moments where moments of magic are clearly visible to them? Is all of this in Bailey’s mind? It clearly can’t be, because we see that others notice what Bailey sees, so how do they also miss so much of what Bailey notices? Are these magical moments just allegorical depictions of what is going on? If so, they’re far too weak and unnecessary on their own, and I think seeing what is actually happening would suffice.

There is enough to like here. The film appears to be shot on 35mm at all times, down to the hairs and dust in the gate being visible (you can even see the flickering of frames fluttering by, and the misalignment of the film through the “projector’s” gaze). This makes Bird feel extremely personal, as if we’re watching the recordings of a tween and her daily life (this also helps sell the magical moments at least a minuscule amount, since you feel like you’re watching what has been captured on film, not what’s been placed there). Then, there is the score, constructed by the elusive, masterful producer Burial (one of my favourite musical artists of all time, so learning that he made music for this film had me instantly intrigued). Burial’s signature ambient, eerie-yet-comforting electronic melodies (with, of course, his token use of record-player-crackling) fill up some of the empty spaces in Bird, and they compliment the visual aesthetic, as if the film was all created in the confinements of one’s home and mind. It feels silly to say, but the aesthetics of the film are strong enough to make even the biggest head-scratching moments worth watching.

The acting is also strong enough to make the regular scenes feel rooted in reality, as if we’re invading the personal spaces of vulnerable, broken people and families. It’s too bad that the film is also fragmented; not chronologically or artistically, but, rather, as one cohesive piece. For the first forty minutes of Bird, I was convinced that I was watching something riveting, but as the film charged through its flaws and uncertainty, I was no longer sure of this. If Bird’s closing remarks are that we are all special and worthwhile, and that we can get through the difficulties of life if we just fight them head on, it’s a bit puzzling why Bird would go through the magical route to diffuse these claims (you can’t face reality by indulging in fantasy; a film like Pan’s Labyrinth handles this better, because fantasy is commenting on the horrors of war through the eyes of a child, and both the real and unreal worlds are shaped and strengthened well enough to compliment one another and work well on their own).

By the end of Bird, as I was encouraged to let my brain’s thoughts run freely through the inspiration of fleeting imagination with one final magical moment, it, instead, led my train of thought down a different direction, and one I’ve never had with an Andrea Arnold film before: “What was all of this for?” Without proper answers, purpose, or execution, all of the visual and emotional highs of Bird only go so far, especially when Arnold has handled the chaotic moments more strongly before, and the fantasy sequences feel like they are still from the first draft of this story. I love the characters in Bird, how they are shot, and the music that follows them. Given the unevenness and perplexing choices, I can’t say that I love Bird as a whole.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.