The Outrun

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

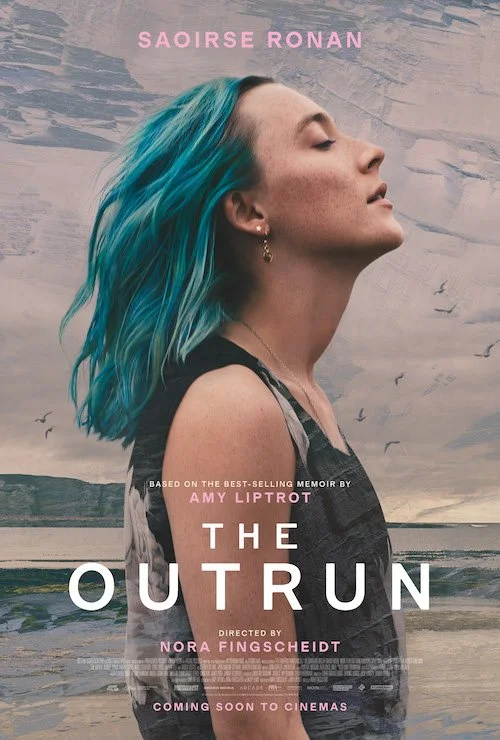

It can be challenging to make a great film about addiction, because the subject matter is typically a repetitive one: a signature sign of being an addict is the inability to stop doing the same, harmful thing to one’s self. This is true for any film of addiction. An example of a film depicting sex addiction that gets lost in its own cycles is I Smile Back from 2015, starring Sarah Silverman, which has a great central performance but also doesn’t know what more to say than “Being a sex addict can hurt your loved ones and yourself.” On the contrary, there’s Steve McQueen’s Shame from 2011, starring Michael Fassbender, which is about the same subject matter but analyzes the destruction of sexual addiction in many ways (all while the stories present go on to deliver more powerful and meaningful talking points). On the topic of alcoholism and/or drug addiction, I won’t go down the list of the thousands of films that have depicted these illnesses, but I’ll instead leap to my thoughts on The Outrun, directed by Nora Fingscheidt and starring Saoirse Ronan. Focusing on the suffering of a young addict, Rona (Ronan), in the Orkney Islands of Scotland, The Outrun likens human vices to animalistic tendencies and urges, all while trying to find a different side to what downward spirals and recovery look like. It partially succeeds.

Told in a non-chronological fashion, The Outrun stitches together memories and regrets with a bit of a haze; as if to say that what we are seeing are within a troubled mind. The Outrun kicks off with a description of the Scottish mythical creatures known as selkies: shapeshifters that can transform between attractive, alluring human forms into free-swimming seals. To me, this can either represent the allure of feel-good substances to those with withdrawal, or this can represent Rona herself: a complicated human who just wants to float. The Outrun fixates on the patterns of migratory animals and their behaviours, particularly since Rona is searching for the endangered corn crake during her recovery process, and the film mimics the concept of travel via the constant walks along shorelines, the hopping from domicile to domicile (or club-to-club, bar-to-bar as well), and the pilgrimage through Rona’s memories and present. Animals may uproot themselves to find answers, comfort, and homeliness. Rona is doing the same.

Saoirse Ronan is reliably sensational once again in The Outrun: a film that tries its best to mean something, but actually does thanks to the thespian’s capabilities to lead.

Rona’s backstory is one full of promise and collapse, as she is enrolled to study biology in London and gets carried away with the nightlife there. Additionally, we get glimpses into her childhood, particularly the separation of her parents, which works better as a reason to have more settings and subplots in the film than as proper context for Rona; sure, having a traumatic event can lead to addiction, but The Outrun showcases how humans are complicated creatures, and having a couple of reasons why Rona drifted off the right path feels a bit simplistic. As we see Rona move around in the present and in the past, we see a lost soul only finding familiarity at the bottom of a bottle, and so relapse is inevitable. I’m grateful that The Outrun doesn’t frame Rona as someone who just has to have alcohol (which I do realize is a reality for many) because observing the willpower needed to truly stay sober is one that strengthens the argument of how awful addiction is to millions of people on a daily basis.

Star Saoirse Ronan is the key element that fills up many of the empty spaces. Their names are similar, so bear with me during this next stretch. We don’t get enough narrative explanation of Rona’s psychological and biological backstory leading to addiction, so Ronan makes her character multifaceted in the present and not predictable (you can actually sense the mental tugs-of-war that she has at any given time). When The Outrun gets caught in similar narrative circles that feel like Rona stuck swimming around in a tiny pool, Ronan’s performance pushes her out of the water to walk on two feet and gain more distance. Ronan is brilliant in The Outrun because she feels like a real person who means well, is capable of greatness, and has a big heart who simply cannot stop making bad decisions but is certainly trying to.

I can’t pretend that all of the heavy lifting is by Ronan, though, because I do find Fingscheidt’s use of animalistic and natural allegories to follow Rona’s quest to get better highly useful; animals don’t know how to quit and will just pick themselves back up again (yes, even the endangered ones who are almost wiped out). As a result, The Outrun is prettier, more intriguing, and stronger than your basic run-of-the-mill addiction films, even though it commits some similar faults. From gorgeous imagery to the fabulous needle drops (especially The The’s “This Is the Day” to close the film out), The Outrun does feel like Rona’s diary, making it vulnerable and enthralling enough to be watchable; I just wish we got the full story, because even the surface works well enough (can you imagine the untapped potential here).

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.