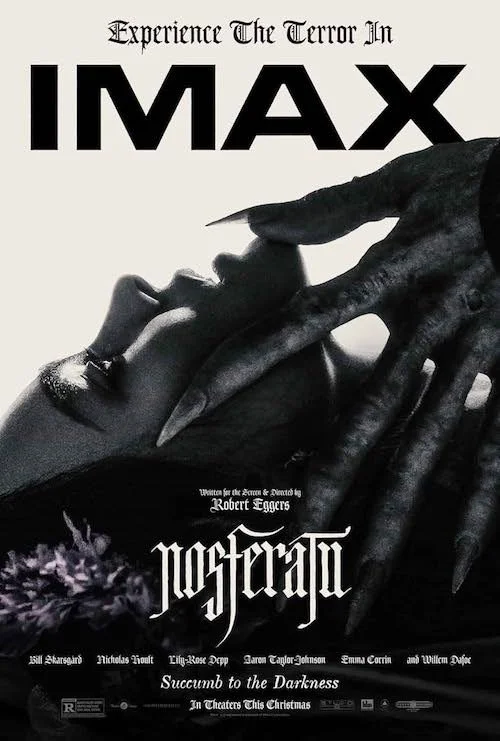

Nosferatu (2024)

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

T’was a film released on Christmas

With a packed movie house.

We enter a gothic castle.

O’er there’s a rat, not a mouse.

We find Count Orlok feasting

on the flesh of mere mortals.

T’was a vision by Robert Eggers,

Yet another horrifying portal.

We traverse time and culture

In a film full of riches.

We’re seen this story before,

previously told without hitches.

Eggers’ vision is tremendous,

worthy of screens big and not small.

Nosferatu is the best film on Christmas,

a holiday nightmare for all!

Truth be told, I’m not sure why Robert Eggers’ latest film, his much-anticipated version of Nosferatu, is released on Christmas Day (outside of there being a very brief mention of the holiday in the film, and the frequent-enough usage of snow and themes of family and love). Since this was the intended release date for the film from over a year ago, there’s clearly a reason outside of Eggers and company wanting to be a part of the ongoing awards season race. Maybe one cannot help but reflect on their loved ones and the hope and faith that keeps us together during this holiday season, and watching Nosferatu during this time of the year may haunt you even more than watching it any other time: you’ll be pressed to reflect on those you are closest to, and imagine them going through the nightmares present in Eggers’ newest motion picture.

You may asking yourself (rightfully so), “Why do we need another Nosferatu?” Over one hundred years ago, we had F. W. Murnau’s silent film classic kick off the way that vampires (including Dracula, who Count Orlok/Nosferatu is based off of) could be represented in film. Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre is the same story but with far more pessimism as we see characters and settings succumb to the darkness; this was released over fifty years after Murnau’s version. Now a century later, Eggers’ version has been released. I’ll tell you this: if anyone else wanted to make this film, I’d have written off the idea. However, likely the only working director today who I would trust with this project is Eggers himself, who has a history of highly-researched visions with dialect that fits era, location, and culture, some of the finest detailing in period-specific cinema, and a control on the horror genre that is fresh, effective, and clever. A new Nosferatu could only come from Eggers, or so it would appear on paper. Apparently, Eggers has been wanting to make Nosferatu for nearly ten years; it was originally meant to be his second film after The Witch.

I’m happy to report that my expectations were met. I got exactly what I wanted from a Nosferatu written and directed by Eggers. If it’s true that Eggers has been wanting to make this film for a good chunk of his life (not only did he want to make this feature for a decade, he co-produced a stage production of Nosferatu back in high school), you can see every ounce of dedication in each and every frame of this film. In that same breath, what I wasn’t expecting — and this is quite the surprise — is that Nosferatu is to Eggers what The Favourite is to Yorgos Lanthimos: an eccentric auteur’s most accessible film while still being unorthodox enough to not be considered safe. Nosferatu has moments of comedic relief amidst the madness, which you’d barely find in any previous Eggers film (if anything, any comedy may stem from absurdity or discomfort). Nosferatu also possesses more optimism, sympathy, and beauty than any Eggers film has previously. Yes, there are elements to this film that sound appealing to the general public. In that same breath, Nosferatu is also just as disturbing and shocking as the director has ever been, so don’t expect Eggers to be going soft on you.

Robert Eggers delivers a terrifying gothic film that closes out a year full of strong horror works with a bang.

The beauty of all three great versions of Nosferatu is that they have different focuses within the same story. Murnau submitted himself to the darkness of German expressionism to evoke new ways that horror could be portrayed on screen with methods that are proven to be effective even a century later. Herzog depicts a world that is surrendering to the plague: an insistence that society is suffering and deteriorating, and no amount of small victories will revert the damage caused. Then there’s Eggers’ version which takes on a psychological approach, specifically how mental illness — particularly in women (which is a subject frequently visited in horror, as can be read about in the informative and thorough book, House of Psychotic Women by Kier-La Janisse) — has been treated over time. There are other themes in the film, but the aesthetic choices and pacing certainly lean towards Eggers’ perception of how poorly society treats those who are in need; when society itself crumbles due to an outbreak (a plague), it doesn’t know how to treat itself, either.

We follow familiar characters with Thomas and Ellen Hutter (Nicholas Hoult and Lily-Rose Depp, respectively) at the forefront. Nosferatu begins with some of Ellen’s night terrors, and they’re quite vicious to say the least. Ellen is young here, but we instantly skip ahead a few years to the “present”. Ellen is saved via love, but her awful visions are returning. Thomas, on the other hand, is a real estate agent with a huge lead that promises him and Ellen a life of luxury and safety. He just has to trek all the way to the peaks of the Carpathians to find the castle of one Count Orlok (Bill Skarsgård) to make this massive sale. He is warned time and time again not to complete this journey by those he passes by, and he begins to have his own psychedelic horrors like Ellen has in the past. Meanwhile, Ellen is staying with the family of her best friend, Anna Harding (Emma Corrin) and her husband Friedrich (Aaron Taylor-Johnson); once Ellen’s illness returns, Friedrich winds up seeking help through a scientist who is fascinated with alchemy and the occult, Professor Eberhart Von Franz (Willem Dafoe).

At times, Nosferatu is Eggers’ answer to a traditional period piece film (albeit a gothic one in the style of Wuthering Heights), but this is a horror film through and through. Eggers wastes no time making you feel queasy, which is a given with his filmography, but what I adore about Nosferatu is how the film itself feels like it is slinking around like the titular creature in the shadows of the film theatre’s darkness. Jarin Blaschke’s cinematography looks fantastic (pale, pastel colours mixed with shadows and pearly white imagery), but it’s the panning that sells the camerawork. When the camera slowly cuts to the right into a dark corridor only to lead us into a new shot we didn’t expect, that’s us understanding Thomas’ delirium within Count Orlok’s castle. When a pan suddenly clicks into a static shot so suddenly it’s as if Nosferatu has possessive control of our head and is forcing our gaze. When the camera drifts forward and gradually raises upward and points downward, we feel like the Count himself levitating above an unsuspecting world below. Nosferatu’s cinematography is reason enough to watch this version when other marvelous ones already exist.

Nosferatu properly encompasses numerous themes with equal prioritization.

For the most part, the acting is stellar and helps carry through Eggers’ quest to balance sensibility (by his standards, anyway) and insanity. Rose-Depp has never been better than she is here. I was a bit doubtful when she was first cast, especially since the Eggers veteran Anya Taylor-Joy was initially meant to be Ellen and had to back out due to scheduling conflicts, but Rose-Depp is highly convincing as Ellen in her normal state of mind (and, somehow, even stronger when Ellen loses control of her mind and body). I feel like Rose-Depp needs the right director in order for her to show what she’s capable of, but at least we can see that she’s got some raw talent if Nosferatu is any indication. Then, there is Skarsgård who is unrecognizable as Count Orlok, which is both a nod to the makeup department and to his booming-yet-mysterious performance. If Skarsgård wasn’t already great at playing characters while under heavy prosthetics and get-ups, then his work in Nosferatu will convince you that he is. Both leads are highly committed and vulnerable in different ways, and they aren’t to be missed.

I’d go one-by-one with each actor and their strengths, but I’d rather cut to the chase and bring up that Taylor-Johnson delivers the one performance that didn’t always convince me was truthful. Without truly hurting the film for me, I couldn’t help but feel that his work as Friedrich — particularly in preliminary scenes — made me feel like this was the one character who didn’t fit in this film, particularly the time period (I feel like Taylor-Johnson’s Friedrich could pull up Twitch on his phone and watch live feeds of Call of Duty at any given time). Having said that, Taylor-Johnson shines more towards the latter sequences of Nosferatu when the chips are down and emotions are high, but since the bulk of his performance felt wooden enough to slightly pull me out of some scenes, I cannot help but bring these moments up as the very few low-points of what is otherwise a spellbinding, sensational film (and, at least, Taylor-Johnson saves himself with empathetic acting towards the end of the film).

Everyone is working towards the film’s concept of the stigmas surrounding mental health, and we see that in how Ellen is treated throughout the feature; from being tied down to a bed to stop convulsions, to her being ignored when she is bringing up that her visions are true and dangerous. However, this isn’t the only running theme of the film. On one hand, Nosferatu tackles what the ongoing issues of our world feel like (hence why a contemporaneous observation through the Nosferatu lens feels fitting): from the shutdowns of a widespread pandemic to the collapsing of civilization and order. On the other, there is a chemistry between religion, the occult, and purity (the latter being represented through both sexual repression and expression). When you combine all of these talking points together, you get a film that questions out loud (literally, at one point) where morality comes from: ourselves, or outside forces. Do we decide how good or evil we are, or are we unable to decide how we behave (especially if we begin to lose our minds)?

Ultimately, watching Nosferatu is like witnessing a loved one be possessed by illness or damnation and, eventually, give in to surrender, making the film not only scary but heartbreaking as well; who cares how brightly the sun shines when we watch the love of our life be punished for existing? As we watch a cruel society ignore the cries of a suffering woman and also not properly tend to her, we see her devoted partner do anything to try and save her; we see ourselves in Thomas and can only imagine the helplessness he feels when there is nothing he can do to protect the person he cares the most about. Additionally, watching Eggers’ Nosferatu tackle the misconceptions between mental illness, sexuality, and purity (whatever the latter means, anyway) is a clear indication of the director looking at an old film and recontextualizing it with a modern headspace: how would this tale read in 2024? The other Nosferatu classics I’ve brought up have their strengths, and Eggers’ version makes us feel like we’re watching a loved one die (either that, or feel like we ourselves are perishing) while being neglected and misdiagnosed; if the film isn’t immediately scary or eerie to you (which I think is an impossibility), its implications will surely haunt you for days, weeks, or years to come.

Nosferatu is an arresting watch that never lets go. It is uncharacteristically graceful for a Robert Eggers film at times, but then it’s as unapologetically dismal as he’s ever been when needed. It feels like a tug-of-war between us living in reality and us falling into our worst horrors. Eggers essentially brings us into hell itself on Christmas Day, which may be a selling point for some people. In a year that has been extremely strong within the horror genre (from The Substance and Smile 2 to Strange Darling and I Saw the TV Glow), Nosferatu still sticks out as a major highlight of the genre. While the aforementioned films showcase new ideas for the genre, Eggers’ Nosferatu truly reminds us how far the genre has come; it concludes the year with yet another brilliant, must-see horror film. The film is flavoured with intense, anthropological research, major artistic and performative commitment, and thematic nuance. In an era rife with nonsensical remakes and reboots, Eggers shows that there can still be imagination and creativity within revitalizing an old property (not to encourage others to try and follow suit to disastrous results, mind you). If anything, Nosferatu may have only worked because of Eggers, which cements him as one of the greatest cinematic horror storytellers of the twenty-first century.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.