The Brutalist

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Warning: This review contains minor spoilers for The Brutalist. Reader discretion is advised.

At the 2024 edition of the Toronto International Film Festival, I’ll never forget what I saw. No, not The Brutalist, although I would have kicked off this review with the same notion if I had. Instead, I saw the director of The Brutalist, Brady Corbet, go up to each and every TIFF volunteer and staff member while his film was running. Unprompted, he thanked each of them for “helping [his] film be seen.” It was an act of humility I usually don’t see at the premieres of feature films, usually because directors and stars are excited or understand the magnitude of their moment and try to own it. Corbet, on the other hand, used this moment to go up to the people who are usually forgotten or overlooked at festivals to help make this occasion theirs as well. What amazes me the most is that Corbet was just crowned the Best Director (or Silver Lion) award at the Venice International Film Festival literally days before (and, I believe, is the youngest winner of such an award at just thirty six years of age). The way Corbet was acting was like a film student whose short film is going to be seen by a dozen curious people. In reality, Corbet was starting to set the film world on fire. Even so, he was as grounded, respectful, and modest as can be.

Now, I don’t give scores based on how nice people are, but I do bring up how polite and real Corbet was — and is — because it feels like an insane offset to how massive The Brutalist feels. You’d think a film with as many risks, ideas, and images as this one would be made by a pretentious “genius,” but instead we find a masterpiece at the hands of someone far more interesting. Corbet is likely best known to many as an indie film actor, attached to some popular and major projects like Thirteen, Melancholia, and Clouds of Sils Maria. His previous film, Vox Lux in 2018, I felt like was an underrated and underseen look at a traumatized youth who goes on to be exploited due to her singing talent; she winds up becoming a pop idol with tons of baggage. While I don’t feel like every idea gelled, most of them did and were far more daring than what you’d typically find from actors-turned-directors (how Corbet came up with mixing the avant-garde score of Scott Walker and the sugar, radio-friendly hits written by Sia will forever astound me given how drastically different they are on paper and yet how well they actually blended together). I knew Vox Lux was just a jumping point, and was eager to see what unorthodox ideas Corbet had next; he clearly had the vision necessary.

Helping me get brought back down to Earth at the end of The Brutalist was the text “In Memory of Scott Walker” to kick off the ending credits: a reminder that, no matter how ambitious and inventive the film I just watched was, that this is a director who never forgets what or who matter most to him. Before that, for three-and-a-half hours (and even during the fifteen minute intermission roughly halfway through), The Brutalist transported me to a different planet, as if I was an alien being eavesdropping on Earth, its inhabitants, and their architecture. Brutalist architecture is defined by its minimalism, the exposure of raw materials, and the allowance of scratches and blemishes to be a part of the “finished” design (in that case, all buildings will forever be defined by their visible provenance). The title is appropriate for the central character of László Tóth (Adrian Brody): a Hungarian Jew who survives the Holocaust and winds up in America, separated from his wife, Erzsébet (Felicity Jones), and niece, Zsófia (Raffey Cassidy). László’s skin, previous nose injury, and other scars and wear tell its own story, as if he is as enriched as the structures he created back in Hungary.

The Brutalist is a film that is so massive and captivating that its lengthy runtime zip by like the speed of life.

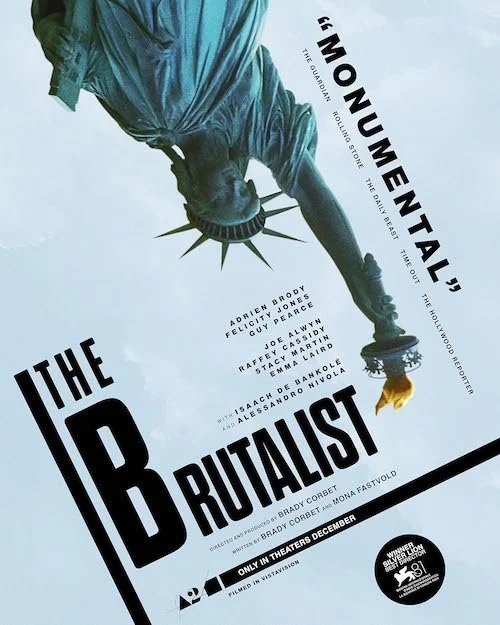

László successfully winds up in New York City after fleeing Hungary and sees the Statue of Liberty upon arrival, in its signature coat of rusted green: a reminder of the striking affect that the best monuments have. Most people know that the Statue of Liberty was a gift by the French to commemorate their alliance with the United States in 1884, but do you know who made the statue? The Brutalist has many goals, and one is to remind you that every monument was made by a visionary. In the case of a massive project that László undertakes throughout this film, The Brutalist tries to highlight this one example. After arriving in New York, László concludes his travels in Philadelphia while the nation is on the cusp of a new industrial and technological age. Part of László’s mission is to ensure the safety of his wife and niece, but the other part is to also take care of himself, and László endures years of poverty (and, as a result of his trauma and struggles, a heroin addiction).

All of this leads up to the untimely connection between László and multi-millionaire industrialist, Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce). After an initial confrontation stemming from Harrison’s lack of approval of the surprise work László was commissioned to undertake by Harrison’s son and daughter, Harry (Joe Alwyn) and Maggie (Stacy Martin), László is met by the wealthy magnate years down the road. Harrison learns of the brilliance of László’s architecture and hires him to take on the massive undertaking of an honorary community centre (in the name of Harrison’s recently departed mother). This project will guarantee that László has money and a place to stay, as well as the fact his wife and niece can safely flee Europe through Harrison’s lawyer’s assistance. This project means everything to László, but in more ways than one. A major theme of The Brutalist, again, is what we see by the end result. A crucial quote towards the end of the film that sets the entire film into a certain perspective is — to paraphrase — that the journey is only a part of the story, and that life truly is about the destination.

For a Hungarian-Jewish survivor of the Nazi takeover in Europe, László is sadly familiar with awful living conditions, and the threat of torture, bigotry, and even death at every turn. His first sight of the United States via the Statue of Liberty is unforgettable: as if he is breaking out of his own prison and finally seeing the light. For most of The Brutalist — a film full of wide angle shots, breathtaking landscapes, and so much open space — we see László living in squalor and/or tiny spaces. How free is László, truly? Even though The Brutalist highlights what made America stand out during the rise of the concept of the American Dream (likely what László was chasing while simultaneously leaving Hungary), it also narrows in on what stands out to László as an immigrant: the quiet chatter surrounding him, the racist remarks to other walks of life (which, to László, means that these people are likely antisemitic behind his back), the double standards that elevated certain people over others, and more. Corbet uses found footage pieces to usher in new years and decades throughout The Brutalist, not just to get us into the mindset of that time period but to also remind us that the American Dream is a constant lie we’re being fed, and it takes being informed too late like László was to realize this.

Brady Corbet exhibits an extraordinary vision with The Brutalist.

It’s clear that Corbet has his own favourite type of shot, and it was evident in Vox Lux six years prior to The Brutalist as well: wide, POV shots of “us” barreling down roads or tracks. The Brutalist uses quite a few of these shots to transition between sequences or passages of time. To me, these are hypnotizing. You focus on the horizon and feel like time is slowing down. When you shift your eyes to the corners or edges of the frame, the speed we’re going looks far faster, as if we’re out of control. Time and speed are relative in their own ways, and by indicating the quickness and slowness of existence (where years zip by, but weeks can drone on), Corbet is reminding us of our inability to stop us from moving forward, from getting older, and from one day dying. Yes, these sequences connect scenes together more than anything, but I cannot shake off how well they represent the speed of life as well, especially when a common theme in Corbet’s brief-but-mighty filmography thus far is us wondering how we got to where we are today (before having the same thought years down the road).

If you are assuming that that’s the only artistic gamble Corbet makes in The Brutalist, you are out of your mind. From the shortest “overture” I think I’ve ever seen (unless the title card is meant to signify the entire preliminary sequence, of course) which gets interrupted by the film itself, to the sideways-scrolling opening credits, The Brutalist starts as creatively as it exists. Almost every single shot, scene, and sequence has some sort of new angle or idea that elevates what could have been a bare basics approach to on-screen drama to pure artistry. There are even awkward cuts tossed in just to keep you on your toes and break up the restfulness some scenes were en route to having. There isn’t a single moment that feels dull here, which is saying a lot given that this film is two hundred hours and twenty minutes (!). I promise you this: The Brutalist feels at least an hour shorter than it actually is. The pacing has a pulse of a freight train that never slows down. The Brutalist propels itself forward at any given opportunity. You’re always interested to see what happens next. You’re forever seeing new artistic designs, concepts, and ideas take place. I wouldn’t remove a second of The Brutalist. In fact, I was furious after my press screening that I couldn’t hop into an adjacent cinema to watch it right away again.

Of course, the fleeting unorthodoxy of a brilliantly-minded filmmaker won’t appeal to everyone, especially if you’re interested in the bare basics of film. Does The Brutalist have strong acting? Absolutely. Brody hasn’t been this good since The Pianist (I’ll give his Oscar-winning turn as Władysław Szpilman the edge since how real and pure he feels here, but Brody is perhaps at his most complicated and multi-faceted here in The Brutalist). Brody makes László — a man inflicted by personal demons — a fascinating soul we can’t quite figure out in just one glance (perhaps as a retort to all of the presumptions made about him as a Jewish man during a highly intolerant time). We can never fault László because Brody doesn’t paint him out as a saint or hero: Brody makes him simply human, even with his ingenious architectural designs. Pearce is likely due for his first (shockingly, only his first) Oscar nomination as Harrison: a boastful, bombastic villain who feels cartoonishly awful in a way that will make you second guess what you’re watching for a split second until Pearce reminds you that people this unashamedly proud, snarly, and slimy do exist. It’s Pearce’s best performance in years.

Rounding up the major performances is Jones’ Erzsébet who is not present for at least half of The Brutalist. When she finally shows up, she is extravagant: a powerful spirit within an ailing body encumbered by osteoporosis. I feel like Jones has never really been given a proper role to explore how deeply her acting chops can chomp, and The Brutalist — even in her shortened performance that begins well into the runtime — is proof that she is capable of gold when given the right opportunities. With the acting out of the way, you may be wondering if The Brutalist is well written. Absolutely. The dialogue by Corbert and his partner, frequent collaborator Mona Fastvoid, is almost always stellar. The Brutalist is riddled with thought-provoking lines that will likely wind up on those film-based social media accounts that cannot stop posting great bits of dialogue. The characters are all rounded but never promised to be good. In fact, almost everyone in The Brutalist is full of sin, particularly in an America that promises fortune in a dog-eat-dog world of opportunists.

The Brutalist is so rich in design and execution that it has carved itself the destiny as an appreciated American work for years to come.

When you dig deeper, The Brutalist has incredibly rich purpose. I especially love the symbols of Erzsébet and Zsófia. Erzsébet is unable to walk or do certain actions or activities on her own due to her ailment. Zsófia is a mute after years of suffering during the Holocaust. Together, we see how a volatile world treats those who can’t act or fend for themselves, as well as the different ways that hardship can carve into us and reshape us in the same way that we reconfigure materials into new molds. There is much going on within The Brutalist, from depictions of capitalist self-sabotage, to the calamity of urgency (as well as the fatality of not moving fast enough). It’s true. The American Dream is all about seizing opportunities. The Brutalist highlights the ways you can do so; you can think only for yourself, or you can think of others. During this film, I was reminded of Richard Linklater’s magnum opus, Boyhood, and his sentiment that we don’t seize the moments: they seize us. This is especially true in The Brutalist, as actions only take people so far. It’s our work — our legacy — that will stand tall once we’re dead and gone. What do you want your legacy to be?

I could spend hours shuffling through the countless things about The Brutalist that astounded me. Daniel Blumberg’s score is a mix between Mica Levi’s triumphant work for Jackie and Jonny Greenwood’s percussive, tense exercises in There Will Be Blood: needless to say, Blumberg’s score is equal parts harrowing and gorgeous. Lol Crawley’s cinematography leans into the experimental tendencies Corbet is gunning for and it succeeds. If you’re not looking at static shots of pure bliss (either in a natural or an architectural sense), you’re being pressed to rethink what you’re looking at (from the obstruction of lights and shadows during a scene of intimacy, or how a cross in a chapel can look upside-down from the wrong angle and suddenly turn a well-intentioned place of worship into the quarters of the devil). I honestly could keep going with each and every element of The Brutalist, but I’ll allow the passage of time to take place in order for the film to be analyzed as fully as it is begging to be. You just know that this will be studied and discussed for years.

Towards the end of 2024 comes a blistering mammoth of cinema. Sure, The Brutalist’s poster states that many publications have shared the word “monumental” to discuss the film, but I honestly don’t think that “monumental” begins to describe it. That only depicts the scope and size of this motion picture, which, to be fair, is ginormous. It doesn’t reflect on the intimacy and the details present as well. As much of a spectacle as The Brutalist is, it’s also insanely fine-tuned. To think that the largest-feeling film of the year was made for around ten million dollars is astonishing to me. How can you accomplish so much with so little? Then I remember the Brady Corbet I saw at TIFF: a man who wasn’t flashy or seeking attention. He just wanted to showcase his appreciation for his passion project being seen, and so he thanked those who made this possible. This is a man who understands how artistry works: not via a budget, but by a vision. No matter what it took, Corbet got the job done. Just as his film professed, it is not about the journey but the destination. Corbet took the moment to appreciate the people in the present; he’s no hypocrite. In an industry — particularly Hollywood — riddled with greed, deception, and self-destruction, Corbert has delivered an American masterwork that recontextualizes what the nation’s cinema can look like if you’re enough of a maverick.

What we’re left with is a film that feels as thorough as hefty literature; as provocative as fine art; as garnished with special traits upon each revisitation as our deepest memories. You can live within the size of this film while also being expelled outside of it and left with your jaw on the floor with what you’re witnessing. During a time where the future of cinemas is at risk, The Brutalist begs to be seen on the biggest screen on 70mm. It is as maximalist as it is minimalist: an observation of what are both too large and too intricate to capture via typical means. The acting is heavily intrinsic, clashing against the structural behemoths that envelop these people. You won’t get every single answer here, but I don’t think you’re meant to either. You’re given enough to work with, and it’s up to you to sculpt the rest via your experience with these characters and their surroundings (those that they stumble upon, and those they are literally making as architects and industrialists). It’s true. It’s where we end up that matters more than the trip there. Where Brady Corbet has wound up is with the best film of 2024. If artists and visionaries hope that their creations carry their legacy, Corbet needn’t worry: The Brutalist, his greatest achievement, is destined to withstand the test of time.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.