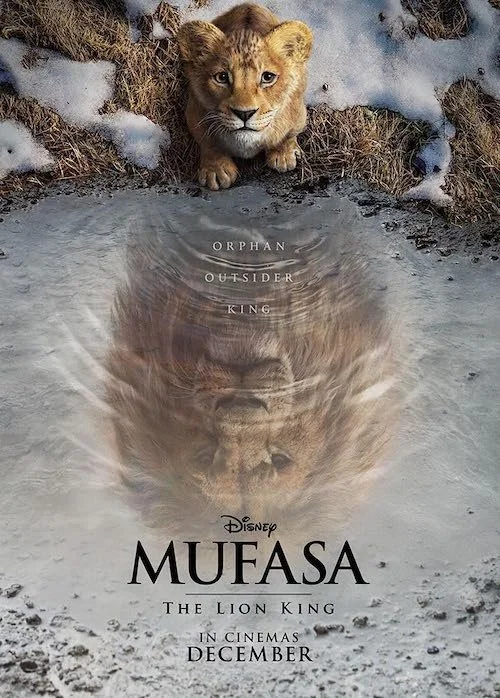

Mufasa: The Lion King

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

It’s been hard not to feel trepedatious about Barry Jenkins making the prequel to Jon Favreau’s swing-and-a-miss attempt at turning Disney’s animated masterpiece, The Lion King, into a “live action” remake (whatever that means). Favreau’s The Lion King is visually stunning, but it feels like a Weekend at Bernie’s exercise where we watch taxidermised corpses sing against their will or ability. Part of this problem arose from the nearly shot-for-shot approach to recapturing the original animated film’s charm and magic, but instead a photo-realistic take on the exact same film (save for minor changes) made the original film’s allure disappear, while the National Geographic aesthetic doesn’t work when these animals talk and belt melodies out, thus removing life from what was meant to feel like us out in the wild and observing nature be fascinating. It flopped on both fronts, and I couldn’t help but worry that Jenkins, who is an even stronger filmmaker, was going to wind up in the same snare on behalf of Disney’s insistence (given the track record of these live action remakes, who else is to blame?).

Well, the prequel film by Jenkins is here, and it’s titled Mufasa: The Lion King. Now, here is a director who clearly understood what feedback was necessary to cling onto after Favreau’s film suffered from backlash (likely against the kind of film he wanted to make). Right off the bat, these animals have far more elastic expressions, making it far easier to tell what emotions they’re meant to be feeling (for instance, a slightly bemused cub in Mufasa will have more life in it than Simba literally watching his father die in 2019’s The Lion King). Secondly, instead of being forced to adhere to the exact images of an older film, Jenkins goes hog wild with his signature style of magic realism to great effect. Mufasa is a genuinely stunning film, one that feels like he is trying his damnedest to push whatever boundaries he’s even allowed to approach. I’d recommend giving Mufasa a shot at some point in your life (maybe not right away, if you don’t feel like rushing to see it) just because of the spellbinding visuals that place you in a hallucinatory dream state.

Mufasa: The Lion King is a treat to look at, even if the film doesn’t wind up being as strong as it could have been.

Of course, looks aren’t everything, and Mufasa begins to struggle in other departments, from the writing to the songs supplied. The story, which involves a young Mufasa being removed from his pride due to a massive flood, and being rescued by another cub named Taka (who will wind up becoming Scar in The Lion King). Mufasa is welcomed into Taka’s family by all except for father, King Obasi. That doesn’t deter Taka from bonding with Mufasa, and they grow up together as adolescent lions when tragedy continues to strike, this time in the form of the bullying of a pack of leucistic lions known as the Outsiders. Without going too deeply into the story, Mufasa encapsulates the lore of The Lion King: the concept of the circle of life, and the seeking of acceptance and family within it. Jenkins works with what he has (even though he does a decent job here, Jeff Nathanson isn’t really the strongest screenwriter of all time, with films like Speed 2: Cruise Control and Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull under his belt, with Catch Me If You Can being his best screenplay), and Mufasa is at least interesting narratively as a result.

However, the story falters once you sense that Disney meddling take hold. Mufasa isn’t strictly a prequel, as it dips back-and-forth between the past and the “present” via the entire film being told in flashback by Rafiki, Timon and Pumbaa (the story of Mufasa is being told to Simba and Nala’s daughter, Kiara). While Jenkins and Nathanson try to make this “necessity” work with a fairly touching final scene that explains the importance of sharing such a story to Kiara, these moments feel pointless otherwise and like Disney’s insistence that Mufasa has to link as much with 2019’s The Lion King as possible. Then there are the inclusions of new songs, written by Lin-Manuel Miranda; while they’re different from his usual shtick and feel faithful enough to what music in The Lion King sounds like, these songs aren’t much to write home about. Between these elements and the sillier moments (fortunately, there aren’t many), Mufasa feels held back by a studio which simply cannot stop getting in its own way.

Having said all of that, Mufasa: The Lion King is actually not bad. It at least doesn’t feel like a carbon copy attempt that was dead upon arrival like Favreau’s honest effort before. Mufasa dives into family dynamics (both blood and inherited) while feeling like a massive celebration of culture, nature, and visual artistry. However, this is still easily Jenkins’ worst film to date, and it frustrates me because you can honestly sense a visionary filmmaker trying to break out of Disney’s grasp throughout the entire film. As soon as I see a mesmerizing shot that feels like it came from the great beyond, I’ll have to be clonked on the head by some cutesy stuff because Disney demands that this remains a family-friendly, safe affair. Even though it sounds contradictory, I don’t feel like Jenkins sold out with Mufasa because of how much of the film feels like the director taking this project as far as he could; you could argue that he still wanted to guarantee his earnings from such a massive undertaking and that he didn’t go far enough if he still made a lot of money, but I applaud his attempt nonetheless and cannot wait to see what ambitious film or series he’ll be capable of with this Disney cash to spend.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.