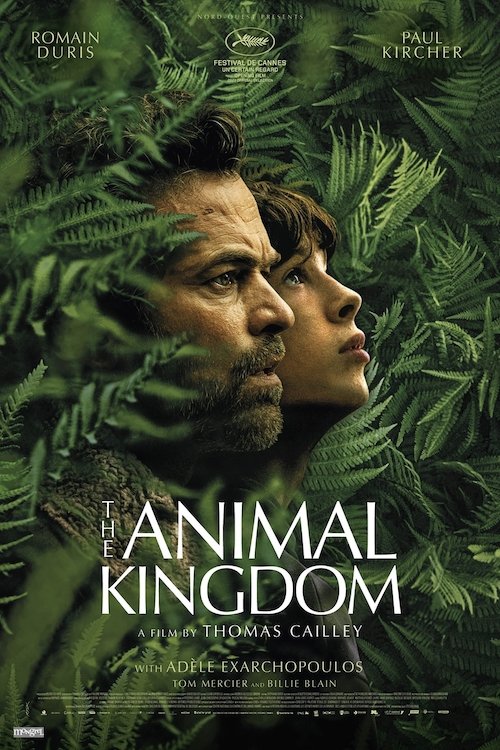

The Animal Kingdom

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Did you want to like The Lobster by Yorgos Lanthimos but find the film just too damn weird? Well, you finally have a new option when it comes to people turning into animals in allegorical cinema. Enter Thomas Cailley’s The Animal Kingdom: a poetic, strange, hazy look at unconditional love during unprecedented times. Before we get into the crux of the film, there’s the barest premise: a condition is slowly mutating some humans into animals of varying species, be they birds, octopuses, or dogs (et cetera). They are referred to as “critters”, and are essentially castigated and maligned by society. You can look at this tragic outcome as an observation of how poorly humans treat animals despite them being living, breathing beings just like us (who deserve to live freely and comfortably). You can even go the extra mile and find the obvious symbolism here: how humans treat one another during outbreaks (be it a case of yesteryear like the AIDS crisis, or something far more contemporary and likely like the COVID-19 pandemic). You can even view The Animal Kingdom as a take on sexism, homophobia, or racism; although I think the actual transformations represent something a bit more on the illness side of things, there’s still something going on throughout this film regarding the dialogue of how humans approach others in any capacity. The film touches upon how people treat those they don’t see themselves in, particularly the unhealthy (or the mutating, in this case) and the hostility and lack of compassion that follows. In that same breath, how far are we willing to go for those we love? Can we find the same respect or care in those we have far less history or similarities with?

In a more direct sense, The Animal Kingdom follows father and son, François (Romain Duris) and Émile (Paul Kircher), who are trying to protect one of their own: François’ wife and Émile’s mother, who is becoming a critter (Émile is quick to proclaim that she is, instead, dead while introducing himself to classmates as a new student in school, because it may be more dangerous or prickly to state the truth here). As a group of these mutations drive themselves deep into a dense forest nearby for solace, François and Émile begin a search for their missing loved one; this is also meant to protect her in case the wrong people find her. On that note, there is also an investigation involving local police officers, including Julia (Adèle Exarchopoulos of Blue is the Warmest Colour and Passages fame, and soon to be in Pixar’s Inside Out 2), but Julia plays a prominent part as one of the good ones: someone who François can seemingly trust in this search and protection. As The Animal Kingdom progresses, it touches upon the notions of a body horror but through a much more loving perspective. François turns to Julia halfway through the film — and the search — and admits that he isn’t sure of what he’s more scared of: losing his wife, or finding her (and what she’s become). It’s as if Cailley got engrossed by the empathy from something like David Cronenberg’s The Fly and wanted to explore these glimpses as an entire feature film. These are the 2020s, and such experiments are possible without too much scrutiny from the general public.

As we continue to get progressively uglier as a society towards our own fellow people, and the world’s status as a habitable planet continues to come into question, the narrative cohesion of The Animal Kingdom works quite well; we’re seeing how humans treat others and animals (either well or poorly) while being pressed to look at the planet as an ecosystem with vegetation and foliage everywhere. We cannot help but acknowledge our own state of things during The Animal Kingdom, not quite as if Cailley’s reality here is representative of the Garden of Eden (or the start of humanity in a biblical sense), but rather something a bit more blatant: humans created civilizations, and we’re on the verge of destroying our own habitats as well. The Animal Kingdom is far more focused on the personal aspect of this reality, though, and it feels a bit like a missed opportunity when you see how nuanced the construction of the film’s narrative premise is; maybe Cailley needed assurance that he could have gone even further with what is a promising hypothesis.

What The Animal Kingdom loses sight of in extreme potential it makes up for with its detailed characterizations and political metaphors.

The Animal Kingdom may fall a bit short of its own potential in terms of scope and scale, but it at least aims to go the full distance with the development and humanizing (ironically) of its main characters, thus creating the main selling point to watch this lovely, peculiar film. As bonds grow and scenarios grow precarious for François, Émile, and Julia, you’ll know that no one here is necessarily protected by hero’s armour plotwise (again, this film has to mirror the unpredictable nature of our own political climates and ensure that the protagonists are free of harm or mutation would be cheap). Cailley isn’t too concerned about solving the impossible but instead finding beauty in the abnormal or the judged (this is heavily prevalent in the subplot involving “Fix”: a critter who is slowly turning into a bird whom Émile meets). The result is more quaint, which may be what you’re more interested in, and that’s something that many science fiction or fantasy films lose sight of as well: a personal connection between the audience and this vast world they've painstakingly made (who cares about all of that work if it blows right past you). On that note, The Animal Kingdom succeeds by making us feel a part of an ongoing dilemma with far more hope and solace than what you may have bargained for before watching.

I can only help but wonder what this film would have looked like with a larger budget than fifteen million euros, as this may have been what limited Cailley from going even further. What we do get is a smaller-budgeted film with evidently hours of work put into makeup and CGI artistry, world-building (as to have the story make sense for humans, critters, and animals alike), and character structure. In a film full of the dedication we show to those we love, this kind of commitment cannot go unnoticed or unappreciated. This isn’t quite the kingdom that the title boasts, but it's more than enough to brush you somewhere else for two hours (while never forgetting what’s going on outside of the cinema or your living room). The Animal Kingdom is an inspired take on impossible conversations and one that may wind up being a newly found gem for some who give it a chance (I foresee some viewers adoring a film like The Animal Kingdom, and you could be amongst this demographic if this review makes the film feel promising).

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.