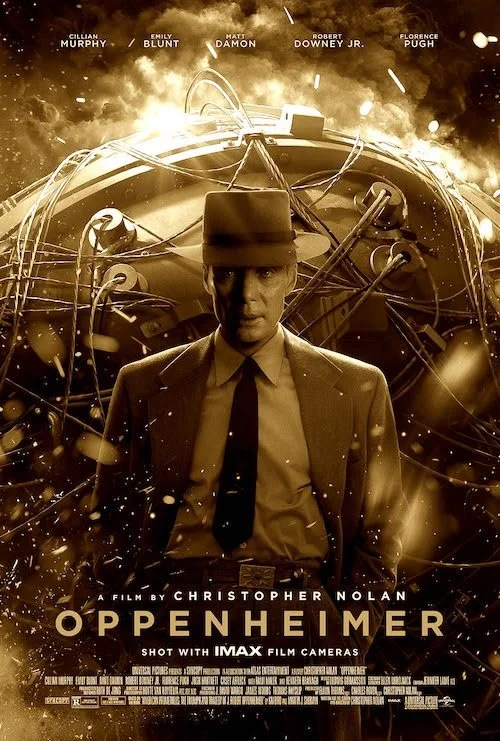

Oppenheimer

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. Oppenheimer is the ninety sixth Best Picture winner at the 2023 Academy Awards.

And just like that, Christopher Nolan went from being the criminally underrepresented director at the Academy Awards to having a film that cleaned up the 96th Oscars. Oppenheimer has had a momentum that could not be slowed down ever since that uniting summer of Barbenheimer. It felt too early to say that this would finally be the moment when Nolan won Best Director and/or Best Picture, but we’ve reached the moment where both have happened, and it somehow feels like it was an obvious win after all this time (despite how competitive 2023 was as a year). So, what was the trick that finally had the Academy come around and honour the very director they’ve been ducking for over a decade? This is the same guy whose film, The Dark Knight, is mostly responsible for the Best Picture category getting expanded to more than five nominees, who was never nominated for Best Director until Dunkirk (not for Inception, not for Memento, not for The Dark Knight…), and whose films mainly picked up technical awards (outside of the posthumous win Heath Ledger earned for playing The Joker in The Dark Knight).

First off, it’s important to remind ourselves — those who agree with me, anyway — that Oppenheimer is easily one of Nolan’s best works (I actually think it’s second only to Memento) and an achievement on all fronts. While that won’t be easy to ignore if you’re the Academy, we’ve seen great films get many nominations and very few wins (in fact, Killers of the Flower Moon and Poor Things were in this very position this year). So, again, what made Oppenheimer impossible to neglect? I’d argue it’s the film’s theme of unstoppable corruption and malice. In the same way a film like The Zone of Interest takes place during the Holocaust but can be applied to any situation where privileged parties turn blind eyes to atrocities, Oppenheimer can be a vessel to understand any monstrous event in the course of history; a study of how it feels embedded in our DNA to react via hostility towards one another, and how we will more than likely be the primary reason why humans will be the downfall of humanity.

With bloodshed going on around us, how can one not feel this way? With the looming presence of our own mortality and extinction hanging over our heads (be it via the push of the notorious button that ends us all, climate change taking its toll on us, the cost of living being impossible to keep up with, et cetera), I think a film like Oppenheimer wasn’t technical escapism despite its obvious roots in action-inspired filmmaking (massive sets, electrifying jumpcuts, escalating tension that leads to erupting payoffs). Instead, it is a unifying film that presents the shocking realization: despite how individualistic it feels to take on the world alone, we’re all in this downward spiral together. We have no choice.

Oppenheimer possesses the filmmaking of escapist spectacles but it never shies away from its important messages about our impending doom as a civilization.

At the same time, as we stare at the hideousness of the human experience for three hours without flinching, we also see the commitment humans are capable of as artists. With career-defining performances from actors like Cillian Murphy (who plays the titular physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer) and Robert Downey Jr. (Admiral Lewis Strauss), gigantically sized sets, jaw-dropping effects, goosebump-emitting music (courtesy of one Ludwig Göransson) and so many other dazzling factors, Oppenheimer is a passion project for all involved, as if they recognized that life is temporary and that humanity’s reign on Earth could end at an instance; we may as well make the most of what we have right now. The end result is a near-perfect experience that is divided into two streamlines: fission and fusion.

Fission aims to decimate the concept of what a biographical picture is typically seen as (by painting everything via intentionally rose-coloured glasses via Oppenheimer’s nostalgia) whilst depicting the chain reaction of events in a way that also feels self-referential and almost fabricated; when Oppenheimer tosses drinking glasses at one corner of his room early on, it’s as if he predicted the very moment his wife Kitty (Emily Blunt) breaks her chalice out of frustration when he refuses to stand up more for himself far later on in the film (every action causes a reaction, and, subsequently, a ripple effect of reactions that all lead up to an end result).

The film would be quite fragmented with just this side of the coin being present, but that’s where fusion comes into play. Told predominantly through the eyes of the highly jealous and persistent Strauss (and in black-and-white, as to not forget how academic, direct, and journalistic these segments of the film are), the fusion timeline does exactly what it says: it converges everything together to make Oppenheimer a complete story (it also provides more concrete depictions of various events, including Strauss’ Senate confirmation hearing). Together, both fission and fusion detail the tug-of-war found within the biographical picture: does a director put their own passion and ideas into the mix and risk being romantics, or do they try to be as factual as possible and lose their artistry within the sterility? Nolan somehow gets away with both in this blend of viewpoints, and Oppenheimer winds up feeling both empirical (fission) and veristic (fusion).

Oppenheimer is a masterfully crafted film that aims to push the boundaries of how biographical pictures can be presented.

Watching Oppenheimer in the day and age of fake news and disinformation adds to the experience. As we watch a man take the fall for entire teams and their decision and efforts to create the nuclear bomb that can wipe out an entire nation (or the planet), we spot the many layers of one-sided bias, loaded decision-making, and backstabbing. We learn that if it wasn’t J. Robert Oppenheimer, someone else would have pulled off making the bomb and getting both the credit and the infamy (as many divisions were intent on this bomb being made and working properly, no matter who wound up pulling it off). No one comes out of Oppenheimer looking fully clean, ranging from their involvement in the Manhattan Project and being responsible for a massacre, to the affairs and dishonesty they partake in. Concerning the unreliability of viewpoints, Oppenheimer is aware of how difficult it is to properly portray complete truth, as can be seen with how Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh) and her demise are showcased (with implications that this was either a suicide or an assassination, the latter given her Communist affiliations).

So, how do you get as accurate as possible in the day and age of lies and deception? Oppenheimer takes the titular scientist’s personal feelings into account alongside those of his opposition, creating a fully-fledged version of a film that could have been instantly written off for either glamourizing a flawed and complicated individual (not once does Oppenheimer feel like a hero here) or a watered-down take on what was already known information by anyone with access to Wikipedia (or those who have read American Prometheus, which this film is heavily based on). To watch Oppenheimer is to see an amalgamation of memory, fact, ambiguity, certainty, artistry, and neutrality: a melting pot of ideas and concepts that render a usually single-note genre a smorgasbord of tones and sensations. It feels impossible to stop like the ripple effects that stem from one action. Its message feels impossible to turn around, in the very way that Oppenheimer concludes this film by stating that the world is already on its way to its end, and this process cannot be stopped.

Then Oppenheimer ends as it begins: with Oppenheimer snapping back to reality while reflecting on what he tells Albert Einstein during the final sequence. He’s back at the hearing of the security counsel who will be stripping him of his Q clearance. It’s a reminder that history repeats itself, we are destined to destroy others and ourselves, and our end is the beginning of the end of the beginning (again, every action has a reaction). The film treats its audience with enough seriousness (it never dumbs down its politics or science) to make us feel like we are at the seat of the table of the restaurant we’re usually never allowed to attend (this feels like a series of revelations of things that are hidden from us so major figures can dishonestly keep their track records clean). It colour codes its timelines to make us feel like we are experiencing everything everywhere all at once (perhaps a similar train of thought to last year’s Best Picture winner and how our histories are our futures and pasts simultaneously). It’s a crucial message to take in as we feel like we are actively watching the world burn and our species dissolve. It’s daunting to accept for three hours, but it’s oddly cathartic at the same time; millions of us sat in the movie theatres last year and experienced these existentialist nightmares at once, and we no longer felt alone.

A film about complicated science, even more challenging politics, the immoralities of many whom we will likely never match in our lifetime, and the lives of those we’ll never meet or be affiliated with, somehow made us all feel seen and acknowledged. Oppenheimer is a technical marvel, a narrative labyrinth, a union between artistic experimentation and blockbuster magic, and an exposition of strong performances by a studded cast who all knew their roles. Lastly, it somehow still feels down-to-earth enough to recognize who its audience is: people who are unable to control what’s coming to them (cinema was seen as an art form for working and lower classes from the very start, and the medium being a means to relay messages to the masses hasn’t changed). This film speaks to everyone, which, given its subject matter, duration, and nature, is actually astonishing when you really think about it. Can you call Oppenheimer a legacy win for Nolan? Sure, if you’re delusional. I think this is the first time the Academy has had no choice but to accept Nolan’s strengths because Oppenheimer is a film that has something to say to all walks of life, is one of the largest events of the year, and plays the Academy game (biopics usually are shoe-ins) via his own ruleset (thank God for that). Everything Nolan has done has led up to this moment: a film that will likely never be forgotten for how it dominated the 2023 film circuit in almost every way.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.