Filmography Worship: Ranking Every Sergio Leone Film

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Filmography Worship is a series where we review every single feature of filmmakers that have made our Wall of Directors

Rarely is a filmmaker who is so intrinsically attached to a genre greatly influential to directors who operate outside of said genre, but such is the case with the legendary Sergio Leone, best known for the five Westerns he made (out of the seven films he directed in total) and the many artists he paved the way for. His approach to the Spaghetti Western movement remains unparalleled by most, outside of a handful of exceptions (like Sergio Corbucci, for example); Leone gets the edge because his affinity for style, tension, euphoria, and grit transcended the low-budgets and limitations he initially had to work with. The son of veteran Italian director and actor Roberto Roberti and silent star Bice Valerian, Leone grew up with those who were pivotal to the cinema scene of his homeland. Leone was initially practicing law but dropped out after he joined his father on many film sets and gained a passion for film, having worked with some other — even larger — titans, including Italian Neorealist legend Vittorio De Sica.

This exposure to film sets translated to a favour Leone had to carry out for director Mario Bonnard, who grew ill during the production of The Last Days of Pompeii; this marked the first film Leone had a hand in directing (I won’t be including it on this list because it’s debatable how much involvement he had with finishing this film, and, as a result, there are merely hints of Leone’s signature thumbprint found in the film). This sword and sandals epic led Leone to his first feature film: a similar historical project titled The Colossus of Rhodes. Quickly realizing that this genre wasn’t his forte (while the reach of historical epics waned simultaneously), Leone turned to the rise of Spaghetti Westerns (a low-budget, European answer to the American Western with a majority of films being shot in Italy), and the rest is history. I’ll get more into particularities with each film entry; there are only seven to go through.

Leone’s destiny wasn’t just where he went, but who he decided to bring along with him. He always had connections even before he realized he did, and this includes a childhood friend by the name of Ennio Morricone, who scored every film from A Fistful of Dollars onwards and would go down as the greatest composer in cinematic history. Leone knew what talent his friend possessed and worked backwards; instead of having a composer write to footage of the film, Morricone would compose first and Leone conducted his films to what he would hear, allowing shots to linger for Morricone’s melodies to play out and not be interrupted. Leone adapted and learned from his peers, including Clint Eastwood who commented on the original wordiness of A Fistful of Dollars; the dialogue in Leone’s films would become snappy, witty, and unforgettable. Leone wasn’t a pushover, mind you, and he had very clear ideas of what he wanted to get out of his films (equating the Wild West to the shifts of society and history, the poor souls who weren’t given a chance and the corrupt who misuse their power, for instance). His sleek yet raw sense of style oozed into everything from the renowned editing in his films to the brilliant cinematography composed of extreme close-ups and extra wide shots; the two styles juxtaposed together depicted feuding minds of silent bandits and the open landscapes that may become their graves post standoff.

Leone spent much time on his swan song project which was a large departure from the Western genre whilst embodying the same themes of morality and guilt. The gangster classic Once Upon a Time in America was butchered by the studio when Leone’s large-scaled vision — a near-four-hour opus that spans many decades and is told non-linearly— was decimated to nearly half its length and edited in chronological order. Leone’s tale of tortured consciousness became a dull coming-of-age tale that was despised by critics to the point that Leone swore never to make a film again: a devastating promise he kept until his death (despite having many ideas that never came to fruition). When Once Upon a Time in America was finally released as Leone intended, it was cherished as one of the greatest gangster films of all time (perhaps the greatest, depending on who you ask).

Due to his exposure throughout his youth, Leone knew what he wanted to see in a film and fought to the bitter end. His certainty — and the occasional flexibility when he saw the great ideas others had — made him a definitive figure in cinema who has inspired directors to the point of complete homage (and occasional thievery). Quentin Tarantino has championed Leone for decades, and you can feel the influence of The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly throughout his career (especially the opening of Inglourious Basterds, which is enough of a carbon copy of the introduction to Angel Eyes in Leone’s film that you cannot deny it). I could make a whole list of likeminded directors who have taken out of Leone’s rulebook, like Robert Rodriguez, Darren Aronofsky, Martin Scorsese, et cetera, et cetera, but I also don’t want to be here all day. As fun as Leone’s films got, they were also painstakingly beautiful; they were as rough around the edges as they were pure art. Here’s to a near-perfect career, a fistful of classics, and a permanent impact on the world of cinema. Here are the films of Sergio Leone ranked from worst to best.

7. The Colossus of Rhodes

It’s easy to call The Colossus of Rhodes the worst film Leone directed by himself because everything else he ever made was great to perfect. Having said that, this sword and sandals epic isn’t really a terrible film. It’s just derivative. It’s as if Leone was replicating exactly what he learned when picking up directing duties for The Last Days of Pompeii and went for the well-established tropes of historical juggernaut films to the point of being cliched (something he could never be accused of afterward). Still, Leone was able to take a small budget and make a film that felt indicative of Hollywood epics, and the scope of The Colossus of Rhodes can be felt if its soul couldn’t (it’s not as though Leone didn’t care, and his heart was in the right place, but there feels like a lack of free reign or exploration). By no means the proper starting point for anyone who has yet to watch a Leone film, The Colossus of Rhodes is a mainly harmless watch for those who want to complete his filmography. You’ll find a longish, decent-to-bland effort with intended flair. Iconic directors have certainly made far worse than the weakest film Leone ever directed by himself.

6. A Fistful of Dollars

From this point on in the list, I’d call every film great to masterful. I preface this entry cautiously because I know A Fistful of Dollars means a lot to many and I, too, think it is a great film. I also think it’s quite simple by Leone’s standards and also impossible to strip away from Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, which was such an inspiration to Leone’s Western that a legal battle for proper rights ensued. We get introduced to the Man With No Name (known as “Joe”, here) who is sought after as a gunslinging bodyguard for the two rival families of a small town. A Fistful of Dollars is quite unvarnished even by Leone’s standards to the point of noticeability (although I guarantee that this is a major draw for many fans of the film), and it is easily the most prioritization star Clint Eastwood (who wanted to branch out from Rawhide at this point, bringing him to Italy for this film) got in the unofficial Dollars trilogy. This is smaller, quainter, and more chaotic than the Leone films that would follow, and I think it’s a strong jumping-off point for a director who was destined for even greater stories and ideas. Here, he was replicating a film he loved in his newly found way. Just wait until he got inspired to drive his own visions.

5. Duck, You Sucker!

Otherwise known as A Fistful of Dynamite, Once Upon a Time … The Revolution (the most fitting title, considering it’s a part of the unofficial Once Upon a Time trilogy), and Leone’s preferred original title before star James Coburn settled him down (Duck, You Asshole!), Duck, You Sucker! is easily the most underrated film in Leone’s career; while not perfect (the Irish and Mexican accents of Coburn and Rod Steiger, respectively, are extremely hit or miss, for starters), it is a strong enough release that doesn’t get talked about enough. Leone’s silliest film for half of its duration, Duck, You Sucker! feels like a buddy approach to rebellion and historical conflict, using the Mexican Revolution of the 1910s as an eye-opening backdrop. The latter parts of Duck, You Sucker! sobers into a far more mature, borderline tragic look at political and spiritual transformation, sacrifice, comeuppance, and the inevitability of war. Leone’s experiment — having a film come of age before your very eyes — doesn’t always work, but when it does, it’s quite a sight to behold; its grandiose depictions of corruption in Mexico feel like a necessary bridge Leone needed to take before Once Upon a Time in America handled a similar concept in a different nation (as Duck, You Sucker! sent off the western genre for Leone for good).

4. For a Few Dollars More

Similar enough to A Fistful of Dollars to draw comparisons, the follow-up, For a Few Dollars More, is where Leone’s career really took off once and for all. Continuing his relationship with Eastwood (the Man With No Name is now “Manco”, here), Leone took the lone gunslinger concept of his previous film and expanded it to a more complete tale of parallels, sizing the acclaimed actor up with the then-neglected Western icon Lee Van Cleef (whose turn as Colonel Mortimer was seen as a resurgence). For a Few Dollars More instantly feels more robust and complicated than A Fistful of Dollars, with the latter feeling like a simple parable compared to the literary nuances and sculpting of the former. Leone’s style is more fully realized here with a larger budget and the proper confidence necessary to make a Spaghetti Western film this assured. Leone was also adopting proper character building with El Indio (Gian Maria Volonté) becoming one of the greatest villains in the Western genre: a disgusting, ruthless man who has enough backstory to make you understand — but never condone — his soulless ways. It was clear at this point that Leone was no longer abiding by tropes: he was creating and perfecting his own.

3. Once Upon a Time in America

Everything else on this list from this point on is cinematic perfection. We kick off this triptych of mastery with Leone’s final film: the aching, exquisite, powerful gangster and crime opus, Once Upon a Time in America. Leone’s complete version was simply too good for us back in the eighties, clearly. We follow mobster Noodles (Robert De Niro) through decades of karma-based anguish as the nation evolves around him and his criminal associates (from children of the street to monumental voices of corruption). As Noodles begins to question his place in the world and on the moral spectrum, he is continuously challenged by Max (James Woods) who aims to go the distance with his version of the American Dream. At nearly four hours in length, Once Upon a Time in America is as complete as a character study and an examination of the United States during its formative years of the twentieth century can be. We saw Leone tackle one genre after his Western reign and he created a masterwork; it pains me to know that there was so much more for him to offer had his original cut for Once Upon a Time in America been released properly in the beginning.

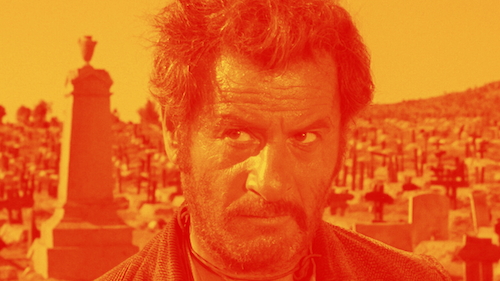

2. The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

If I had a list of the most impactful films in my life as a cinephile, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly might be number one on said list. Teenage me was only prepared for the endless fun, the one-liners, and the fiery action. I didn’t account for the underlying gorgeousness, the prevalent agony during the Civil War, and the stunning aesthetics that elevated this film well above the popcorn romp I was anticipating. The Man With No Name returns one final time (he concludes as “Blondie”), and Lee Van Cleef (now mercenary “Angel Eyes”) is there alongside him. This is Tuco Ramirez’s show (Eli Wallach), and it’s easy to see how these characters are introduced as the titular good, bad, and ugly members of society, given their natures and personalities (the title of the film also predicts their fates). When set to the goings-on of the Civil War, we see the moral ambiguities of war and society near the tail end of the Wild West; all three characters, and many of the prominent side faces, possess traits of all three descriptions. This race to find hidden gold as society burns is one of the most exciting films I’ve ever seen, down to a top-ten climax that I’ll never shake off no matter how many times I watch it. This is the classic Spaghetti Western as its traditional definition: a blending of genres, nations, styles, and techniques in a melting pot of prestigious exhilaration. This was my favourite film as a teenager, and my favourite Western of all time for years.

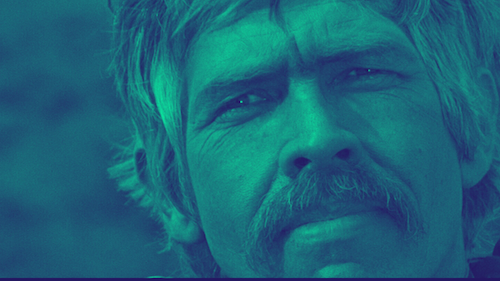

1. Once Upon a Time in the West

I’ve had to face the bittersweet reality. As I get older, I identify more with Once Upon a Time in the West: a film I always adored (and placed second after The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly as the greatest Westerns). The film feels more my speed now. It is more mature, methodical, patient, artistic, and spiritual. The endless fun of The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly is replaced with the tightrope walk of tension, as long, droning lulls erupt with calamitous gunfire. We panic, wondering who got hit by bullets after we endlessly waited to find out beforehand. While Leone’s previous Westerns felt like they marched to the beat of their own drums, Once Upon a Time in the West was all about playing with expectations and delivering abrasive aftermaths while we were at our most vulnerable. This truly was a wild west. Long moments of silence and waiting are full of histories of resentment, anticipation, and trauma, so these seconds to react are stuffed with purpose. As America gushed over the tide of its New Hollywood movement (and the possibilities of taboo rule breakage), Leone was past the sandbox phase of his career and wanted to discover what his punctilious side was.

We are planted at the end of the Wild West era, as civilizations begin to grow, authority and corruption get transferred from the bandits to the elite, and the differing ambitions of what makes an ideal America get conflated into a miasma of greed and innovation. We follow Jill McBain (Claudia Cardinale) whose entire family — which she just married into — has been slain by assassin Frank (Henry Fonda working shockingly against type), the latter who was hired by a railroad tycoon. Jill is watched over by two unlikely guardian angels (in a very unorthodox sense of the notion): lone wolf “Harmonica” (Charles Bronson at his very best) and outlaw Cheyenne (Jason Robards). Once Upon a Time in the West is a far darker Western for Leone: one that isn’t afraid to show the destruction of innocence in a world driven by evil, and the necessary hope that helps rebuild (quite literally, in this sense) society. As the West comes to a close, this film ushers in the Machine Age quite fittingly with the one motif that’s a part of both eras: the intention to welcome a train at a brand new station.

If the Western genre is meant to give credence to the concept of the lone ranger facing the world, Once Upon a Time in the West has one particular lone spirit finding solace in a couple of others as they face the uphill battle of the world. The film honours the classic Western without feeling confined by it; Once Upon a Time in the West is highly subversive for its time due to the narrative turns and daring portrayals of America it was willing to take. This is a tasteful revisionist Western: one that isn’t aiming to completely shake off the films that came before it, but one that is also willing to explore undiscovered frontiers. Its worth isn’t just its drive: its timelessness is unmistakable. As evil evolves and permeates to welcome new innovative ages while killing off the eras prior, we look to the few who are willing to stand up for what is right. Leone was seemingly that figure within the Western genre, and he was looking for the golden-hearted saviours of society while making this film: maybe the same souls who persisted in the Italian Neorealist works he witnessed on set. As Leone sees it, good will prevail just as assuredly as that train will arrive right n schedule, and comeuppance will roll around as well, be it generational (through the persistence of a traumatized child who has grown up with vengeance on their mind) or instant. On the topic of revenge, Leone also asks the difficult question: will it soothe a damaged soul?

As I age, I see the brilliance, importance, and permanence of Once Upon a Time in the West. I feel it in every Western that came after it. I sense it while playing both Red Dead Redemption games (two of the greatest video games of all time). I witness both Leone’s warnings and promises in the world as it envelops me with each new phase of this rapidly changing reality. As the world gets more dire, the good souls within it shine brighter. Once Upon a Time in the West embraces America as a nation of good, bad, and most certainly ugly in an even more textured way than its predecessor, as we see the extents of sin and progress converge with one another. Once Upon a Time in the West is a marvel of production and artistry while possessing a rich story full of soaring purpose and mythological allegory. It is the greatest Western film of all time, Sergio Leone’s magnum opus, and one of the strongest motion pictures I’ve had the honour of seeing, feeling, crying during, and being shaped by.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.