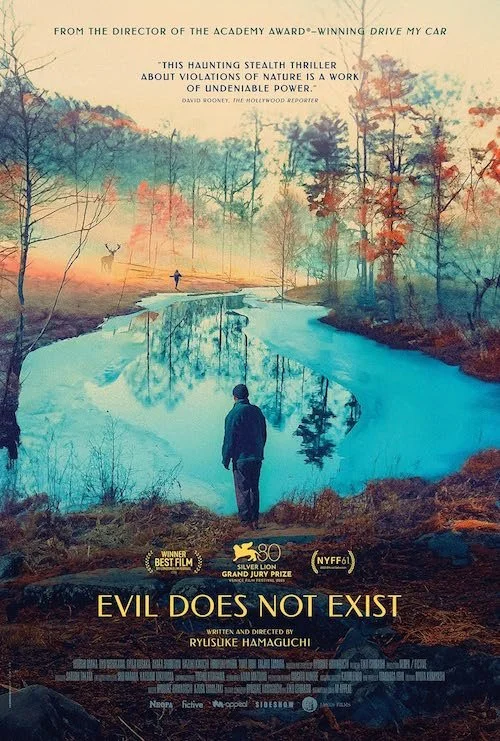

Evil Does Not Exist

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Warning: Mild spoilers for Evil Does Not Exist are present throughout this review. Reader discretion is advised.

It takes a lot to follow up a film as monumental as Drive My Car: an intrinsic epic that won audiences all over the world over despite its allegiance to arthouse and glacial cinema. It was up for Best Picture and Best Director at the Academy Awards, and its reputation continues to grow; I feel like the film only gets stronger with time and contemplation. Japanese director Ryusuke Hamaguchi has had a lengthy, prolific career before this watershed moment, but more eyes were on his next move than ever before; rather than look back at works like Happy Hour or Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy (which arr well worth your time, by the way), the world wanted to know what would come of his follow-up, Evil Does Not Exist. It hit the festival circuit late last year and is finally available to the masses as of this month, so the world has its answer: Hamaguchi has still got it. Rather than trying to double down on the scope and length of Drive My Car, Hamaguchi operates with an hour and a half, which feels meteoric in comparison. Drive My Car is an adaptation of a short story by the legendary Haruki Murakami, and Hamaguchi’s minimalist, airy, figurative style matched the former’s writing perfectly. With this original screenplay for Evil Does Not Exist, Hamaguchi’s expertise in languid cinema prevails.

The film is book-ended by lengthy, droning pans of trees, as we enter and exit the allegorical forest (perhaps the very one of that expression “you can’t see the forest for the trees”, as Evil Does Not Exist hopes to dispel the insular takes on major, global concerns like the destruction of nature). We are eased into the arborescent crux of the film, and out of it when we are forced to marinate on the arresting final sequences (the latter is crucial, because Evil Does Not Exist’s credits barely run, so you may be finding yourself confined to your seat and staring into nothingness and searching for answers otherwise. Considering how short the film already is, these mesmerizing passages are indicative of how brief yet calculated Evil Does Not Exist is particularly with its dedication to possessing much oxygen and space; this is a rare one-hundred-minute film that takes its time as opposed to feeling the need to force as much out as possible. It’s curious how Hamaguchi took a Murakami short story and turned it into a three hour opus, because it almost feels like Evil Does Not Exist is his attempt at making a “short story” (it was meant to be a thirty minute short initially, after all), as very little occurs in terms of plot structure and turning points, and yet the film embodies complete spirit, grief, and dread.

Evil Does Not Exist is a terrific successor to Drive My Car and an assuring sign that Ryusuke Hamaguchi will not compromise his vision as an auteur.

Similar to Drive My Car and other Hamaguchi films, we kick off with a lamenting widower, Takumi, who is a single father taking care of his child, daughter Hana. In response to the calamity of the COVID-19 pandemic, Evil Does Not Exist projects a world and society in desperate need of healing as we zero in on Takumi’s life in the village of Mizubiki, which is now being threatened by a real estate developer’s urgency — contingent with the subsidies relating to the pandemic which has just come and gone — to deforest enough to create a glamping site (just the fact that Hamaguchi chose the privileged concept of glamping over camping is a sign of his economical resourcefulness, and how much is being said via so little). There are many causes for concern, from the nearby septic tank being overused to the destruction of the ecological habitat of others (the decimation of homes of others just so humans can temporarily camp in style is an eye-opener), but the real estate tycoon is incessant on making this project come to fruition. This is indicative of many times in history where the cries of the masses fell on the deaf ears of the greedy; need I bring up the notorious Dakota Access Pipeline for starters? Do I even need to keep going?

During Evil Does Not Exist’s protest against the forced realization of passion projects for the elite and the ramifications for the rest of us (human, vegetative, or animal), we have a subplot involving hunting: another form of slaughter. Hamaguchi cleverly uses the metaphor of a fragmented, analeptic family to resemble what hunting creates when animals are slain. Daughter Hana becomes attached to the idea of animals — particularly the local deer — living freely, as if one of them may be her mother reincarnated; as someone who has lost his own mom yet isn’t spiritual, I can attest to the hope that I am reunited with my loved one in any capacity. We hear gunshots in the distance, often reminding us of the annihilation that we cannot contain while we are fixated on slowing down one such problem via the attempts to stop the glamping project; greed and evil will always prevail, and we sadly can never win all fights against them when they are this rampant. Father Takumi tries his damnedest to make a good life for young Hana and lead by example in this film, and his patience and fortitude are exemplary qualities for a character who acts and speaks on behalf of literally everyone else when it comes to how we respond to the threats of death and change for the benefit of the rich (while the rest of us suffer even more).

Evil Does Not Exist says so much with so little. It is a strong exercise in having you feel its talking points as opposed to blathering on about what Ryusuke Hamaguchi finds frustrating.

As Evil Does Not Exist progresses, it leads up to a climactic moment that transcends time and space: one that mimics the crippling sensation of being caught amidst a fight-or-flight response and also tending to your life flashing before your eyes. Correlating trauma to a deer freezing in front of a car’s headlights, Evil Does Not Exist understands that trauma and grief do not work linearly and that our worst moments fuse together like a tapestry of desperation: if memories are our broken pieces, we do our best to reassemble ourselves, even if we are imperfect. Does Evil Does Not Exist’s conclusion take place in the present? Is it a fusion of past and current events? Its ghostly nature makes it hard to fully understand, but its pain is as clear as ever. That is what resonates the most. If you find all of Evil Does Not Exist to be sedative until this point, even you cannot deny the immediate impact of this moment of narrative crossroads: one that is far more effective regarding the concepts of loss and the impossibility of properly preparing your child to face the world’s dangers than, say, the 2005 Best Picture winner Crash. Not even Takumi — who tried his hardest to be the best dad — knows what the right way to shield the younger generation from the horrors of the present is (be they the state of the planet and civilization, or the never-ending curse of grief).

It is in this final moment that Hamaguchi places us in a similar position, as we watch ourselves kill Mother Nature, separate animals from their families, and destroy the economy of our own people. We get to a point where we have to stand in the way of the next threat, feel forced to respond with kindness and nurture, and know that we are likely to be penalized for our actions while the billionaires that are destroying everything around us (and even us, period, end of sentence) get away with literal murder. The title Evil Does Not Exist is an interesting one as you can read it in a few ways. I personally see it as a calming exercise to try and negate the monstrosities around us, as we find the vivid colours and spacious landscapes of Hamaguchi’s film to be sanctuaries for us to nestle in. You can view the title as something true to Hamaguchi as evil is not a natural construct but one that humans concocted to take advantage of others. As we grieve the loss of our loved ones — and Hamaguchi is right there with us — we also grieve the death of our planet in Evil Does Not Exist: a surrender to the idea that sins cannot exist if nothing does. If we erase everything, including ourselves, of course nothing else will remain. Not even concepts. And it’s all in the name of glamping and other privileges for the fortunate while the rest of us burn.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.