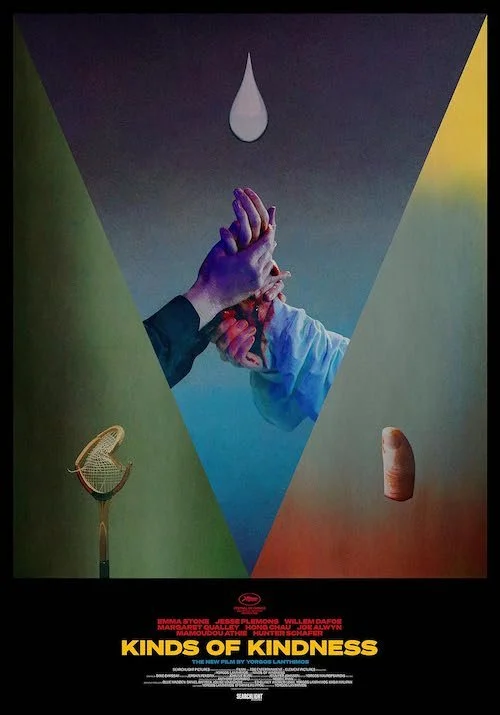

Kinds of Kindness

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Warning: Spoilers for Kinds of Kindness are present throughout this review. Reader discretion is advised.

I am not usually a huge fan of anthological films. I find that the compilation of multiple stories or short films into one feature is setting up the overall picture for highs and lows, especially if one story outshines another, or a particular narrative lags behind and sets the whole feature back. Exceptions have their reasons for resonating. Pulp Fiction connects multiple stories into a fragmented parable of morality where we see cause and effect (and not necessarily in that order). Amores perros connects the misfortunes of people within the messy cycle of life. While I cannot place Greek master Yorgos Lanthimos’ latest film, Kinds of Kindness, on quite the same pedestal, I’m more than happy to call this latest attempt at the anthology film a strong effort with proper consistency and purpose for existing. I’m not blind to the lukewarm reviews this film is getting since its Cannes Film Festival premiere, but I’m not going to just follow the masses if I feel differently which seems to be the case. While not a perfect film, Kinds of Kindness is far stronger than the reputation it currently has. Why do I think this way? I posses the same traits that Lanthimos has: I’m Greek and grew up studying Orthodox Christianity as a child. We speak the same language.

What I think most viewers are missing are the many layered subtexts Kinds of Kindness carries. Instead, it’s become trendy to think of Lanthimos’ films as disturbing, quirky, absurd, and challenging. While all of these qualities are true, they’re also a disservice since the majority of his films are also incredibly well thought out and meaningful. Such is the case with Kinds of Kindness: a trilogy of short films that are stuffed with allegories that are presently being shrugged off simply as strange stories. If you’re Greek like me, you’ll recognize the oft recited trilogy from our youths: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. The three states of God that get honoured in Christianity are God the higher being that watches over us, the human form (Jesus Christ) who sacrificed Himself to save humanity, and the spirit that prevails. I think Lanthimos is likely a lapsed Christian who has reservations about either religion as a whole or the current state of faith, and Kinds of Kindness is the largest exposition of his concerns to date. It feels like the works of Luis Buñuel: well versed yet critical of organized religion, its practices, and beliefs.

We have three short stories that all honour the three concepts of God. Here, they are represented by the stories of R.M.F.: an acronym that, according to Lanthimos, doesn’t carry any specific meaning (but that is hard to believe). I wish I could find the one reddit threat I saw a highly plausible answer within (and I don’t want to take credit from someone else), but a user’s explanation that R.M.F. stands for “redemption, manipulation, and faith” makes the most sense, given the different themes of each story. R.M.F. as a person appears in each story as well. In the first story, “The Death of R.M.F.”, the character is meant to be killed (while having his own death wish). Part two is “R.M.F. is Flying”, and he makes a brief appearance as a helicopter pilot responsible for the saving of main character Liz. The final part is “R.M.F. Eats a Sandwich”, and he appears in the nick of time at the end of the story as a cadaver meant to be revived. R.M.F.’s involvement varies in each story (from very important to barely), yet each story is titled after him. He acts as the sacrifice necessary for redemption in the first story. His heroics encourage the manipulation of reality and of loved ones. It is the faith in the capabilities to bring him back to life that wrap up the story and the film. Maybe Lanthimos wants us all to have our reasons why the character is named R.M.F., but he clearly has his own.

It’s time to get into each story in depth. “The Death of R.M.F.” feels like a modern take on the challenges Christians face when trying to appease God. Robert (Jesse Plemons) works for Raymond (Willem Dafoe) and answers every request the latter has with open arms, including who to marry and how to carry out his life. When Raymond asks Robert to kill R.M.F. via a vehicular crash (stylized in a very ritualistic way), Robert cannot bring himself to murder someone else even if the subject wishes to die. Robert finds his happy life vanishing at the snap of Raymond’s fingers: a clear depiction of God giving and taking away. As we watch Robert floundering to be happy again and struggle with this very demanding request, we see ourselves in the one sided relationship with faith. This is where you either believe or you don’t. I’d argue that Lanthimos doesn’t, given the abuse and insanity Robert goes through because he refuses to take away the life of another. When he eventually gives up and drives over the corpse of R.M.F. with his truck, it’s through a roundabout: the circle of life, death, rebirth, et cetera. Robert has obeyed, but at what cost? That’s what Lanthimos leaves us to grapple with.

Next comes perhaps the most cryptic parable of the triptych, “R.M.F. is Flying”. Officer Daniels (Plemons) is worried about his missing wife, marine biologist Liz (Emma Stone) who has vanished and lost at sea. She winds up back home one day, but feels different: she isn’t the wife he once loved and remembered. This Liz is willing to sacrifice herself to appeal to her husband, but he loses his sanity by noticing more and more dependencies in her behaviour and biology. In a weird way which may come off as blasphemous, I couldn’t help but find Liz resembles Jesus Christ quite a bit, from her appearance not matching the faith that believers had in her (she doesn’t meet up with the expectations of her husband) to her willingness to give herself away to showcase her commitment and unconditional love. After he is deemed delusional, Daniels continues pushing Liz, first by asking her to chop off her thumb and cook it for him to eat (otherwise, he refuses to consume what she makes for him), and then demanding she cuts out her liver for him. The thumb is Liz’s body, and her liver is her blood: a clear sacrifice resembling what Christ promised His disciples.

Once Liz dies giving everything she had to Daniels, the “true” Liz appears at the door of their house, fully embraced by Daniels. We don’t see if this is truly the “real” Liz or another failed clone, but we do see the old Liz corpse at the forefront of the scene where the reborn Liz enters from behind. Jesus was only loved after he came back from the dead. I read Liz’s self abuse and proclamation that Daniels beat her as the torment Christians believe Christ endures for our sins, especially because I don’t feel like Liz is lying as much as she believes Daniels did hurt her; we never fully get the answer as to whether Liz is insane or Daniels is, so this fable becomes far more open to interpretation.

Kinds of Kindness takes religious allegories to a whole new twisted level via Yorgos Lanthimos’ dark vision.

Finally, there’s “R.M.F. Eats a Sandwich”, which represents the Holy Spirit: the faith that God’s presence after His death as Jesus Christ is all around us. This comes in the form of a cult that champions bodily purity in extreme ways. Practitioners Emily (Stone) and Andrew (Plemons) follow leaders Aka (Hong Chau) and Omi (Dafoe): an obvious representation of alpha and omega (the start and end, via the Greek alphabet). This short story is adorned in white imagery representing purity, spirituality, and cleanliness. The clear outlier is Emily’s fancy car which is a rich purple (in the Greek Orthodox church, purple and white are heavily used during the Easter period to acknowledge the death and rebirth of Jesus Christ), and her brown clothes that she wears in pretty much every scene (I saw this as her being pegged as unclean: a theme in this episode). As Emily and Andrew try to find a woman with the ability to bring people back from the dead, they also try to follow the practices of their cult.

Emily gets violated by her former husband (Joe Alwyn) and is instantly seen as unclean and is subsequently cast out by her cult: a clear depiction of how many religions see abused women as the sinners and not those who abuse them (a problem that sadly still prevails in this day and age). Emily fights to cleanse herself, and in doing so fights to find the woman who can bring the dead back to life (while literally scrubbing herself and sweating out any impurities so she can again be pure). She vows to at least be pure in her own eyes, if not those of her apparently former church. Her quest is met by the revelation of a twin (both sisters played by Margaret Qualley); twins represent life and death in Greek culture. One twin is meant to be dead, and the other granted the ability to grant rebirth.

These twins came to Emily in a dream, via one synchronized swimmer cutting the hair of the other who is trapped underwater via her hair (the cutting of said hair is the sacrifice of self to experience freedom). Dreams prevail in all three of these short films. In the first, Robert dreams of his asking for forgiveness from Raymond, and imagines it going poorly. He confronts Raymond the next day and acknowledges that he is plagued by this curse of his life being ruined. In the second film, Liz remarks on a dream where humans and dogs swap places; maybe a confession of the demand — or lack of — obedience and subservience. Religion is a personal belief, and dreams are the revelations of our subconscious. I believe that the protagonists of these three films are driven by their inner thoughts to the point of desperation and insanity, and it is only when they are met with responses or results that they feel fulfilled; these responses include the acknowledgements of ritualistic sacrifices. What is asked of these lambs is carried out in demented ways only to be met with exaltation.

There are many other religious images throughout that can be scrutinized, from the insane Babylonian orgy (a pornographic video including all of the main, rotating actors of the film) to the literal levitation of a “dead” body (one of the Qualley twins being hoisted up by a lift), but I think you get the gist of how thorough Kinds of Kindness is. The next order of business is clarifying that this film, while incredibly multifaceted, doesn’t quite always work. While there is a purpose for everything, this film still very much feels like three short films (or featurettes) that exist and then simply don’t once the final set of credits begin. What may have worked better is if all three parables were intertwined via non-chronological means, so that we can experience all three buildups and downward spirals at the same time: a symphony of darkness and martyrdom. Instead, all three stories start and end sufficiently on their own, but Kinds of Kindness as a whole doesn’t quite resonate as largely as it could. Still, I believe that this film is being given the cold shoulder now, only for it to garner the adoration and analysis that is due in the future. I may even appreciate the film more as time goes on and I discover more subtext and entwined themes. I wouldn’t ever pretend that Kinds of Kindness is amongst Lanthimos’ best films, but I’m here to defend it as another great entry in the filmography of a contemporary master.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.