Twisters

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

I do not care for the 1996 film Twister. I think it is an intended rip off of what was making James Cameron a big time director (from the special effects and action sequences, down to the one liners that land far worse), with a major lack of care or empathy for its characters (who feel like archetype stereotypes). The only upside, I suppose, is how advanced the tornadoes at the forefront of this film felt for their time, from the crunching sound work to the scope and detail of the CGI. These don’t matter nearly thirty years later, so I have very few reasons to even care or revisit this film in 2024. Speaking of this year, we have a followup film that no one really asked for (not at this point in time, anyway), directed by perhaps the least likely person imaginable: Lee Isaac Chung, better known for Minari (one of the best films of the 2020s so far). Maybe it was the massive paycheck that could lead Chung to even greater projects that drew the Korean-American director to this release, or it could be the intention to bring a commentary about the state of America and the obsession with the American Dream that is present in Minari that made this unlikely partnership come to fruition. Whatever the case may be, we’re here, and now so is Twisters.

Needless to say, Twisters is a step up from the 1996 film by Jan de Bont, simply because it is far less annoying (which is always a plus in my opinion). Chung also focuses on the cinematographical beauty behind destruction and emptiness, which makes Twisters at least interesting to look at (even outside of just admiring the tornadoes like in the previous film). Finally, Chung tries to prioritize the characters and their personal histories a little more than Twister ever did. Outside of these efforts, however, Twisters is not vastly better than Twister: just marginally so. A major issue is how similar to the other film Twisters is, which wouldn’t generally be a problem especially if a remake or sequel vows to improve upon the original film (like Twisters does), but here it forgets a major reason why Twister is a failure: the story just isn’t interesting enough, whether it is sequinned with cliched one liners and sight gags (Twister) or aims to be a more wholesome, triumphant project (Twisters).

Twisters involves meteorologist and former storm chaser Kate Carter (Daisy Edgar-Jones). Having sworn off her previous life as a tornado follower, Kate is persuaded to partake in the test of a new tornado detecting system because of its ethical causes when she comes across the content creator Tyler Owens (everyone’s favourite capybara-turned-human, Glen Powell); Tyler and his posse feel like the renegades of the previous Twister film who are careless and selfish with their obsessions with — and profiting off of — tornadoes, until Twisters enlightens us. Nonetheless, just like Twister, Twisters is heavily focused on the races to tornadoes, their increasing sizes and calamities, and the implementation of technology to both better read these events and create a human-versus-nature component in the story. While not a note-for-note remake, Twisters is similar enough to Twister to prove its futility: there can’t be any major improvement if one doesn’t understand all the ways that the previous version is flawed.

Twisters can only be so good when it was made without the full understand as to why Twister doesn’t succeed.

Firstly, the constant following of tornadoes in the ways that go on in both films is incredibly unnatural and difficult to believe: as if they are sentient beings that come back stronger and angrier. Of course, these are only films and they’re not rooted in reality, but storytellers cannot rely on this fact alone before pouring a bucket of farfetched nonsense in our laps and expect us to do all of the cleaning up ourselves. I’m willing to believe a few tornadoes can “behave” in such a way, but not the amount that either film is begging me to trust. Secondly, it feels challenging to feel bad with people who gamble their own safety by continuously going after tornadoes until they nearly die; at least Twisters has a bit more going on so we can see the reasons why these protagonists are going the distance, whereas Twister was a far bigger, karmic mess in this way. Even with Twisters’ shoehorned reasons for these protagonists to keep getting further and further into personal trouble with these tornadoes, the film feels like the rest of us and those within the film are paying for the price of the thrill-seeking or negligence of others. Again, the film tries to insist why we must go about things in the ways that we do, but it doesn’t mean that everything adds up.

At least if Chung was given full control (which, to me, it appears as though he wasn’t), Twisters could settle with its take on compassion and self realization that appears to be going on in the film between characters and each other, versus characters and the tornadoes. Unfortunately, Twisters feels swept away by the Hollywoodization of what could have been a far more grounded take on a tale that was already riddled with tropes and laziness. Between the extremely heavy use of recorded hits and the “snappy” dialogue used, sure, Twisters isn’t as irritating as Twister is, but it still feels held back for much of its duration: as if we’re seeing a film that was meant to sell more than it was to connect. I can only hear the board meetings in my mind: all the hypothetical ways that Universal and Warner Bros. quivered in their seats and worried about dollars whenever it was even remotely implied that a key montage wouldn’t use a popular song to truly “seize” the moment. The songs aren’t the worst, but honing in on what they are is missing the point. I cannot truly immerse myself in a film that is more concerned with being marketable for a moment than opening up for its audience for a lifetime (or at least trying to).

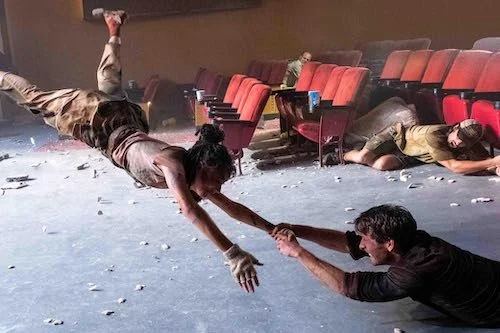

By the end of Twisters (which at least feels genuinely climactic compared to Twister), I could tell that I only cared so much; my worries for the characters came from performances by actors who worked their hardest; my astonishment was created by the magnitude of the special effects that overtook everything I could see. I still had no true investment with the film as a whole, but rather this sequence as it was playing out (once it was done, I was once again detached). If storm chasing is about the rush one feels for a lifetime after seconds of devastation and endangerment, consider Twisters the opposite: a brief amount of success within many hours, weeks, months, and years of hard work that barely lasts. Its purpose may be earnest, but Twisters set out to be the revitalization of a blockbuster that — for some damn reason — continues to be brought up by nostalgia fiends and only delivered what feels like an AI-generated understanding of what makes a film successful: effects, big names, music, love, and meme-able dialogue. This was meant to be Lee isaac Chung’s first Hollywood film post Minari, but instead we got a typical Hollywood film that is somehow attached to Lee Isaac Chung; in this case, it is the storm that conquered the human, despite his best efforts.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.