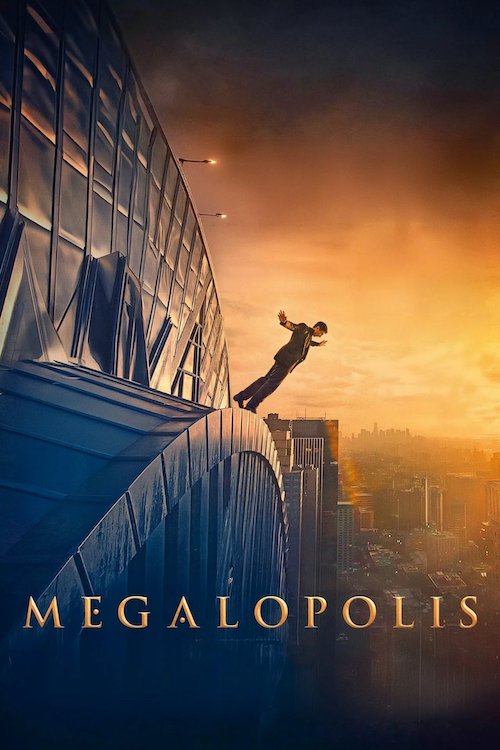

Megalopolis - Dilan's Version

Written by Dilan Fernando

We usually don’t double down on reviews of new films here on Films Fatale, but Francis Ford Coppola’s latest film, the highly anticipated Megalopolis, is the kind of project that may warrant the two reviews that Andreas Babiolakis and Dilan Fernando have written, just because of the insanely polarizing nature of the film. You can find Andreas Babiolakis’ review here.

This review will certainly contain spoilers for Megalopolis. Reader discretion is strongly advised.

There’s a short scene in Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid (1969) that establishes the spirit which propels the two protagonists throughout the film ultimately making them folkloric heroes. Butch and Sundance ride horseback through a canyon as the sun sets. Sundance laughing says, “You just keep thinking, Butch. That’s what you’re good at.” Sundance’s face gleams in the sun for a moment before being engulfed by a shadow cast from an overlooking cliff. Butch looking at the sunset replies, “Boy, I got vision and the rest of the world wears bifocals.” The essence of this scene is what makes the divided audience laugh, scoff, and cringe with contempt at Francis Ford Coppola’s exclusive early screening of his latest and most audacious film Megalopolis (2024).

Megalopolis is an apologue of the progression of mankind’s frivolous nature within a crumbling infrastructure. The fate of New Rome, the 21st century metropolitan city that the film takes place in, is held within the hands of its inhabitants. Cesar Catilina (Adam Driver) a young architect and CEO of the Design Authority an architecture firm. Fundi Romaine (Laurence Fishburne) life protector-advisor of Cesar. Constance Crassus Catilina (Talia Shire) Cesar’s seclusive and neurotic mother. Charles Cothope (James Remar) Cesar’s chief Design Authority advisor. Mayor Cicero (Giancarlo Esposito) who presides over New Rome. Julia Cicero (Nathalie Emmanuel) the mayor’s radical daughter. Jason Zanderz (Jason Schwartzman) the mayor’s assistant. Nush ‘The Fixer’ Berman (Dustin Hoffman) the mayor’s personal aid. Wow Platinum (Aubrey Plaza) a TV personality who doubles as a capitalist femme fatale. Hamilton Crassus III (Jon Voight) an unwittingly wealthy oligarch. Clodio Pulcher (Shia LaBeouf) the grandson of Hamilton Crassus III. They are all integral parts powering the film’s engine – vision.

Of the many different interpretations and discussions the film will generate, Coppola’s narrative imperceptibly alternates between three personal statements that are at its source. One, a portrait of a tortured artist (visionary) with Cesar being an allusion to Coppola. Two, a foretelling of the destruction and fall of mankind. A possible reference to the old studio system of filmmaking and the unviable demands of creating cinema. Three, an allegory for sharing a vision (finding a solution to help repair the world and unite its people). In illustrating this vision Coppola layers the film with a motif based around reflection. A lifetime of reflection on successes and failures throughout his career is present in every frame. Megalopolis opens with Cesar on the ledge of a clock tower looking down at the busy street below. Coppola’s use of dolly zoom references the opening shots of Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) with James Stewart’s character. Coppola efficiently immerses the viewer into Cesar’s mindset.

From this moment onward New Rome, whether good, bad or indifferent is viewed from Cesar’s singular perspective. The opening creates an overwhelming feeling, possibly echoing Coppola’s feelings during the tumultuous productions of The Godfather (1972), Apocalypse Now (1979), and The Cotton Club (1984). The distorted reflections of the world and its members shape Cesar’s transparent vision to create something better for the future. Shots of people walking by windows, rain droplets on car windows resembling a microscopic view of molecules, and the divided loyalties of characters struggling to understand what makes a sustainable life, are all woven into a dysmorphic tapestry.

Capitalism and materialism are the possessory factions of New Rome. Coppola’s shot compositions subtly reinforce his point that the state the world is in is due to the idolization of propagandic idealism. Cesar who’s regarded as a blind prophet hopes to enlighten New Rome’s people and bring them salvation. An example is a scene where Cesar returns to a cluttered home to find Wow Platinum fixated on a television; watching an interview she did with Hamilton Crassus III about his ever-growing wealth. A reflection of Crassus’ face is projected onto a window overlooking New Rome. A close-up of Wow shows the unbridled lust she has for wealth, power, and respect. She caringly manipulates Cesar while awaiting his imminent success, though she grows impatient. Cesar being a visionary lives a life of internal seclusion, hysteria, and self-doubt, all repurposed into the pursuit of creating great art. Cesar’s excessive use of alcohol and drugs are his way of bearing this burden. Continuing on a path of self-destruction, he desperately hopes to find someone to believe in him despite having people who support him. Living in the shadow of his greatest achievement, discovering megalon (an indescribable element with limitless possibilities and uses) without it, would he have garnered what little support he does have?

Megalopolis is Francis Ford Coppola's angle on the current state of the United States and the world, and his hope that we will finally head in the right direction.

Mayor Cicero, Crassus III, and Cesar all meet for the unveiling of Cesar’s latest project, the building of a new metropolitan city to replace the decaying and decrepit New Rome. Coppola frames the scene in a wide shot with the associates of each interested party (the audience) watching from afar surrounding the trio of men who take command of the room, debating their reasons for or against the project. Among the audience is Julia, who is so intrigued by Cesar that after the project announcement begins following him from a distance (perhaps to take a glimpse of his creative process). She has her driver follow Cesar’s town car around the city. Cesar looks out the car window as the archaic statues and structures of the city become animated, toppling and crumbling. Cesar asks Romaine to stop at a flower stand, Julia watches him buy a bouquet of flowers. Cesar stops at an apartment building, Julia follows. Carefully approaching Cesar down a dark hallway, she looks into a well-lit bedroom and sees Cesar gingerly place the bouquet on a bedside table. He bends down and delicately brushes the hair of a bed-ridden woman. In the blink of an eye the woman disappears, Julia realises it’s an apparition and leaves. This is the first and pivotal moment that begins the budding romance that will bring together the differing ideologies present among New Rome’s citizens. Julia succeeds in not only understanding the source of Cesar’s need to create but unknowingly is already a part of it – seeing his vision firsthand.

Arriving unannounced at Design Authority for an impromptu meeting. Cesar casually eats breakfast entertained by Julia’s visit in spite of her father’s political views. She admires Cesar but refuses to acknowledge or communicate it, though she already has. The scene has the emotional drive of the first conversation between Emmanuelle Riva’s, Barny and Jean-Paul Belmondo’s, Léon Morin in Melville’s Léon Morin, Priest (1961). Julia finally stumbles upon the hope for something-someone to believe in; she challenges it, tests its durability, and surveys its commitment. The connection that develops from this interaction leads to Julia working as Cesar’s assistant. The pair attend a wedding reception celebrating Cesar’s Uncle Crassus’ marriage to his new bride Wow Platinum-Crassus. The event doubles as an opportunity for Cesar to provide doubters with a glimpse of his genius, after designing a dress made entirely out of megalon for a young popstar Vesta Sweetwater (Grace VanderWaal), the event’s headlining entertainment.

During the festivities Cesar drinks heavily and pops pills (self-imposed punishment). Amidst the chaotic energy of the party comes one of the most beautiful and poetic sequences in the entire film. Julia tries to limit Cesar’s excessive drinking and drug use in an effort to prevent Cesar from drifting further away from his true self and into a more erratic and insane personality. Cesar wildly runs throughout the party, Julia pulls an imaginary rope as Cesar tries to trudge forward fighting the restraint. Ultimately, he manages to break free and continue on his own to search for more drink and drugs, armaments to be used in the war against his own limitations. Julia trying desperately to rein him in proves her devotion to him and her resilience to cherish his vision. The scene concludes with a drunken montage that Coppola assembles to provide the audience with a first-person look at an artist’s mind – pulling them in different directions, each one pointing towards a threat. The frenetic energy and anxiety present throughout the montage resembles the drunken nightmare that Jean Gabin’s Bobo has in Moontide (1942), which was designed by Salvador Dalí. This entire sequence mirrors the relationship between Coppola and his late wife Eleanor during the making of Apocalypse Now. Uprooting his family and settling in the Philippines for the entirety of the production, without Eleanor there would be no film and the subsequent documentary detailing its fruition, Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse (1991).

Megalopolis is unlike any other film before or to be made after it. It pushes the cinematic medium and manages to be a tribute to Coppola’s greatest influences, D.W. Griffith, Abel Gance, Sergei Eisenstein, Fritz Lang, Orson Welles, and Stanley Kubrick - all cinematic visionaries. The film seamlessly offers reverence to great innovators while showing there’s so much that still has yet to be discovered of an artistic medium that has been corroded by figures. It displays a sense of artistry at such a high degree that it will undoubtedly go over the heads of imperceptive audiences. Throughout the screening, ridiculing eyes dissected every frame and shot with scornful laughter sporadically erupting from the audience before becoming consistent. Sinking into my seat, overcome by a feeling of sadness for a moment, I pondered the words uttered by Cesar in the film illustrating his utilitarianism (harnessing megalon to benefit the sustainable growth of mankind that transcends mortal conception). Cesar says aloud, “There are two things people cannot look at for long. The first is the sun. The second is their own soul.” Coppola shows time and again he’s willing to aim for the sun while bearing his own soul in the process.

Dilan Fernando graduated with a degree in Communications from Brock University. ”Written sentiments are more poetic than spoken word. Film will always preserve more than digital could ever. Only after a great film experience can one begin to see all that life has to offer.“