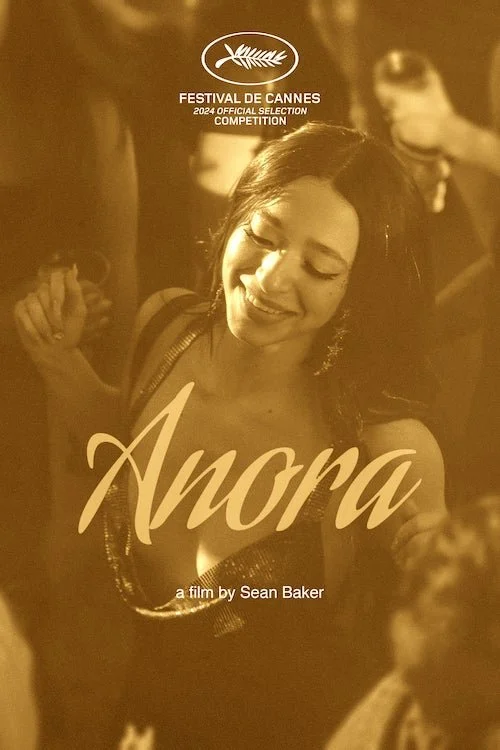

Anora

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. Anora won the sixty eighth Palme d’Or at the 2024 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Greta Gerwig

Jury: J. A. Bayona, Ebru Ceylan, Pierfrancesco Favino, Lily Gladstone, Eva Green, Hirokazu Kore-eda, Nadine Labaki, Omar Sy.

Warning: The following review is a part of TIFF 2024 and may contain spoilers for Anora. Reader discretion is advised.

A lasting image I’ve had in my mind for the past ten years is the final sequence of Sean Baker’s breakout dramedy Tangerine. We see the transgender sex worker Sin-Dee Rella take off her wig after what is arguably the worst day of her life, and just sit in silence. She bares her soul, and sits in silence in a laundromat. She feels like there is no path forward from here. Her co-worker and friend, Alexandra, offers her own wig to Sin-Dee so that the latter can see the best version of herself again and know how to keep going in her own way. Baker’s films show the most neglected people of the world, be they sex workers, impoverished children, or porn stars (retired ones, too). He humanizes the walks of life that most humans refuse to acknowledge or respect, and breaks our hearts once we see these same folks through Baker’s eyes. All decent people love their fellow person and don’t wish any harm to them, but Baker has vowed to do more than that: he wants to make neglected people icons.

This brings us to the latest Palme d’Or winner at the Cannes Film Festival (and the first American one since Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life): Anora. Gone are the days where Baker would use an iPhone or stripped down production to film documentary-esque footage of unfortunate souls. Anora is his biggest production to date and it shows, with the pseudo-celluloid look to evoke the milieu of seventies cinema, much more refined techniques than before (and Baker has always made the most with whatever tools he has, and could make a masterpiece using a colonoscopy camera if he really wanted to), and a focus on wealthy people for once (which, in return, means expensive sets). With Baker operating at his fullest potential so far, it’s safe to say that Anora should be a hit, right?

That would be underselling the film. Anora has instantly become Baker’s strongest film to date, which says a lot when this is the same mind behind Tangerine and The Florida Project. The former film is an electrifying comedy-drama that is intentionally messy and chaotic. The latter is Baker’s most gut wrenching film to date, as our hearts bleed for these unfortunate kids and families who have to face uncertainty every day. Anora has components of both films and an additional one that I haven’t quite seen from Baker before: being so thrilling that I couldn’t catch my breath at times. Baker has shown what he can do with very little, but granting him a proper budget and enough control proves what more he has up his sleeves. Anora is brilliantly written with one of the smartest screenplays of the year; the kind that ticks off every screenwriting 101 topic including amazing character development, the proper implementation of repeating ideas, and every plot thread covered and resolved, all while not being predictable either. The film is riveting, and Baker makes damn sure that anyone watching the film (even those who devalue sex workers) fall in love and have their hearts break for Anora (or “Ani,” as she prefers to be called). No matter who his protagonists are, Baker respects and cherishes all of his characters so much so that you will, too.

Anora is a sensational film by Sean Baker, so much so that its eccentricities are sure to break the barriers of preconceived notions that less open-minded viewers may have.

Ani (Mikey Madison) is a Uzbek-American stripper and escort who lives in south Brooklyn, New York. She has to pretend to love her clients on a daily (well, nightly) basis. She is great at her job even to the point of envy of at least one other stripper. She is also capable of speaking Russian because of her late grandmother who couldn’t speak English (we don’t get too much backstory as to how Ani wound up here, but we do get enough details to know that Ani has clearly had a disjointed, rough life that has led her up to this point). Since she is bilingual, she is asked by her boss to entertain a Russian client one night. He is Ivan, or “Vanya” (Mark Eydelshteyn), and he is clearly made of money seeing how frequently and richly he tips Ani. Vanya cannot get enough of Ani and invites her back to his place repeatedly. At first, this relationship seems to be strictly business, and mainly to fulfill Vanya’s sexual needs (which don’t take long until he’s tossing on his PS5).

Then, Vanya professes love to Ani. He tells her that he doesn’t want her to leave after a week together, and that he also doesn’t want to be deported back to Russia. He asks to marry Ani. At first, she doesn’t believe him because she is so used to having to lie about loving her clients that she is convinced that any acts of true adoration towards her must be fake. She then accepts his proposal when she understands that he is serious. She will never have to worry about working her jobs again (despite Baker’s efforts to dispel the stigmas surrounding sex work in this film, he still wishes for Ani to have a life where she doesn’t have to partake in this industry), and she seems genuinely happy to start her new life and never have to suffer again. You see, Vanya isn’t just rich: he is stupid rich. He is the son of a Russian oligarch whose name is so widely known that typing in a couple of letters into Google will have the rest of his moniker pop up.

This also means that every single move Vanya makes will be caught by the paparazzi or nosy social media hounds, and this wedding is instantly broadcast online. This news circulated, and within a couple of weeks, word gets out to Vanya’s parents in Russia. They order Toros (Karren Karagulian), a hired supervisor of Vanya (of sorts), to force the newlyweds to have this union annulled instantly. Of course, Vanya and Ani don’t want to separate at all, and they’re not given much choice once Toros and some goons storm Vanya’s mansion and refuse to play nice. From this point on, Anora becomes a spicy, turbulent ride that had my preview screening of critics guffawing, cheering, and applauding (believe me, it takes a lot to astound cinephiles who have seen more films than a majority of the rest of the planet combined). It’s not all just drama and calamity, mind you. Baker guarantees proper character growth; Ani begins to take a step back and question the entire situation, the antagonists get some texture that never justifies their methods but at least explains their urgency (they get humanized enough that they feel real), and those we feel like we could once trust disappoint us with their true colours. If you think Anora will be nothing more than a stripper and her husband having a rough time, you are likely far too close minded and unwilling to understand the magnificence of this feature.

Mikey Madison delivers the performance of a lifetime as Ani in Anora: one that is as charismatic and entertaining as it is soul crushing.

Without giving too much away (this paragraph will at least be somewhat of a spoiler, so reader discretion is strongly advised), Anora’s conclusion is another Baker moment that will likely resonate in my mind for many years to come. It involves a proposed truce that doesn’t quite happen, and Ani preparing to face her future. It’s the realization that she no longer wants to pretend to love people she hates, and she breaks. There is support for her during this time, but it doesn’t matter when she is tired of being cared about by those she has no feelings for or connections to. She wants something real, and it may now never happen; like every other Baker conclusion, there is much darkness ahead. The pitch-black credits sequence begins to roll. The majority of the film, particularly the blissful moments, is full of bouncy club beats. This outro serenades us with the uneven thudding of windshield wipers that never ease up. Fantasy will always sweep us off our feet, but it is the crashing back down to Earth that will always hit harder than this elation.

This point is driven by a tour-de-force performance by Mikey Madison who will make you laugh, gasp, and cry. When she isn’t being a badass who doesn’t take shit from anyone, she is revealing herself to us as a human being. Baker briefly makes sure to frame Ani as the sex object that many strip club enthusiasts devalue her as, but he is also quick to prioritize all of the ways that this is very much a human being who deserves compassion, comfort, and support. Madison makes this happen because she never loses sight of who Ani is; even when she is at her job and entertaining, I fully know what is going on in Ani’s mind because of Madison’s challenging acting. I feel like so many other filmmakers and actors would fumble the responsibility of this character and story, but Baker and Madison are a tag team made in heaven: a daring director and an even bolder star working together to bring this story to life. You may not find a more vulnerable performance this year, as Madison leaves it all on the big screen (and Baker makes sure to not miss a moment of this dedication).

Anora is the kind of film that I feel like everyday film goers (the non-judgmental ones, anyway) will get a massive kick out of, but the film will reveal itself for those who are wanting to dig deeper. The concept of what separates adults from the immature (including the act of having to do whatever is necessary to get by, even if not preferred) is a prevalent one; those who have never had to struggle to live don’t understand how to make logical moves in life. In reality, life doesn’t grant us much good luck for the most part; only a very few amount of people are fortunate enough to never have to worry. A co-worker of Ani’s tells her that she has won the lottery when she marries Vanya, but misfortune is far more prevalent than these rare moments of success. Anora encapsulates the whirlwind sensation of this entire spectacle: the rise and fall of love, fortune, and reality. Most people on Earth don’t get that proper ending, let alone the Hollywood life. Baker knows this. He is always aware of giving us the hard-hitting truth: while our stories don’t end here, we, like his characters, are finally done lying to ourselves that there is a greater life waiting for us to stumble upon it.

I know it may seem strange on paper to champion a comedy-drama about the sloppiness of a fast-paced marriage to a stripper this much, but I insist that Anora is one of the top films of the year. To call this film electrifying doesn’t seem like it would do the title justice. It is dangerous, hilarious, witty, and relentless, without a single moment that feels out of place or unnecessary (yes, even if you go back and rewatch the “sex shots”, as Madison would call them, you’ll find that Baker is saying something new with each one). If you think Baker is just indulging in taboo subject matters and images, you are sadly missing out on the substance of what he is saying (and are only focusing on the surface: the very kind of shallowness that Baker is trying to get you to stop resorting to). If you are still blindly dismissing this film, you don’t deserve Anora: a phenomenal character study, showcasing of superspeed storytelling, acting exposition, and exhibition of finding light in the darkest places (and vice versa). One of the meanings for the name “Anora” is “light”, as is specified in the film. Maybe that’s why she protagonist goes by Ani; like most of us living in an economical nightmare that refuses to quit, she’s tired of having to be her own source of optimism and resolution.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.