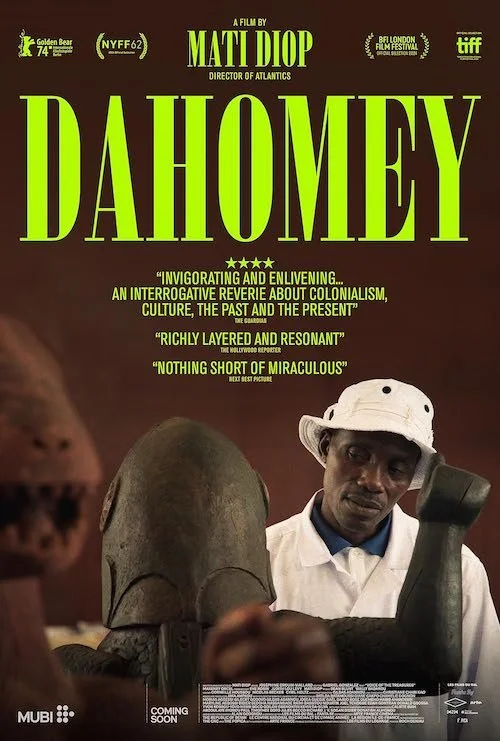

Dahomey

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

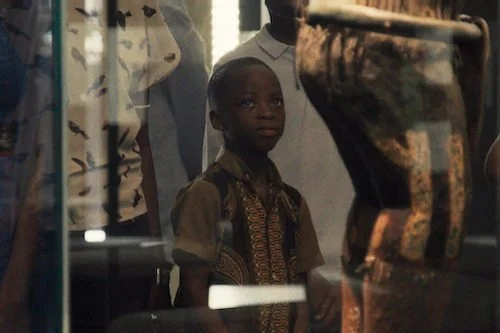

If artifacts could speak, what would they say? That’s one aspect of Mati Diop (the French director behind the fine feature film Atlantics) wanted to get to the bottom of with her documentary feature, the extremely brisk (it’s not even seventy minutes) study known as Dahomey. Named after the West African Kingdom of Dahomey (which folded in 1904 after wars broke out against Dahomey and French colonialists), Diop’s film dives into the discovery of twenty six artifacts which were once seized by the French and are now being returned to the newer country of the Republic of Benin via the act of repatriation. Diop’s film acts like an art gallery for the resurrected objects by showcasing them one by one, and its airy, inviting aesthetic honestly makes Dahomey the ultimate example of a cinematic exhibition (as if you are wandering through these displays and learning about Dahomeyan history).

A running concept is a focus on a pitch black screen with voice over narration (by Haitian writer Makenzy Orcel); this eventually reveals itself to be the perceived “voice” of the final object to be revealed (a statue of Dahomeyan royal, King Ghézo, who ruled until shortly before Dahomey was no more). As if we are listening to a spirit of the departed reflecting on the ruins of his kingdom, Dahomey brings us closer to the importance of provenance, restoration, and repatriation: there’s no authenticity in rewritten history. While these artifacts were being shown in a Parisian museum for years, they weren’t being valued as they were meant to be, either designated as discovered treasures by the French or a sign of forfeit by Dahomey (neither are true). With Diop’s film, these objects are rightfully returned — not just physically but via legacy as well — to the nation and the people they belong to.

Mati Diop challenges how we perceive seized artifacts with Dahomey: a thought-provoking visual essay on colonialism and the need for repatriation.

As the voice over — which sounds other worldly in its booming cadence — prefaces what we are to see, we watch curation take place; Diop turns an installation space into the resurrection of a country, as if we are watching structures be rebuilt before our very eyes. Sadly, an exhibition can only go so far, but Dahomey shows how they can do enough justice to the countries, nations, and people who were destroyed, neglected, and hidden by the monstrosities of colonialism. By opening day, Dahomey makes the act of wandering around this gallery space feel like the touring of an abandoned village, with us seeing what remains. Diop, on the other hand, tries her hand at giving voices to the dearly departed of an older nation to great effect.

Other documentaries may be flashier and aim to wring out the emotions of these moments. Outside of the inventive concept of having one artifact “communicate” on behalf of the Kingdom of Dahomey, Diop allows these discovered objects to speak for themselves. Subsequently, Diop reminds us of the richness and power that historical findings have and their necessity in connecting us with history. While it seems obvious on paper, in 2025 — a time where people forget how resourceful the internet can be, history is being fabricated by conspiracy and miseducation, and the hateful distort truths on purpose — a film like Dahomey is highly important, not just because of the necessity for us to appreciate artifacts and these kinds of exhibits, but also due to the ongoing concern that we are only getting less in touch with our pasts (which, I’m sure I don’t need to tell you, is a crisis).

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.