I'm Still Here

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Do I even need to explain who Walter Salles is when it comes to Brazilian cinema? Central Station is a staple of the nation’s film scene, starring the adored icon Fernanda Montenegro (who is still very much acting at the age of ninety five [!]), and perhaps one of the great Brazilian motion pictures. It helped establish Salles as a wonderful storyteller when it comes to examining the human spirit, particularly while on the road. He further cemented himself in the United States once Central Station became a global smash hit with the Oscar winning The Motorcycle Diaries, horror film Dark Waters, and — obviously, given what I previously said — the lukewarm adaptation of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road; the latter would be his last film until 2024, and his last road film of any kind to date. Still, Salles’ name is a major one in Brazilian — and global — cinema, and his latest feature, I’m Still Here, has been a highly anticipated title since it was first announced.

I am thrilled to say that the film is well worth the wait, so much so that — while Salles is quite strong at making road dramas — I cannot help but anticipate more centred films like this one. If anything, and it could be the recency bias talking, but I think Central Station has now met its match since I’m Still Here is so damn good that I am presently feeling like it is Salles’ strongest release thus far. This political drama is compelling, thrilling, and anxiety inducing. However, it isn’t like Salles to fully submit himself to darkness since his films are always so full of life and electricity, and I’m Still Here is also infused with strong-headed optimism and a lust for life; this only certifies the damnation of its central plot line, but it’s the yin and yang of existence at the forefront of this film.

I’m Still Here is unfortunately based on true events: the arrest and vanishing of former congressman Rubens Paiva (played here by Selton Mello) years after the 1964 Brazilian coup d’état. However, we don’t watch from Rubens’ perspective, given the lack of clarity as to what exactly happened to the political figure (outside of the outcome of it all, I suppose). Instead, we remain at home (ironic for Salles, whose films usually plant us on course to multiple destinations) with Rubens’ wife, Eunice (Fernanda Torres), and their numerous children. At first, Eunice plays the strong maternal figure of trying to calm the situation down; she aims to assure her family that Rubens is going to be okay and is in safe hands. Then again, she is also being coerced by the same kind of toughs that essentially kidnapped Rubens in the first place (like telling close friends that Rubens is on a business trip to explain his absence). However, Eunice quickly changes her tune and vows to be a fighter for the peace and safety of herself, her family, and her missing husband. This doesn’t go over well and results in both harassment and even torture for both Eunice and various family members.

I’m Still Here is an exhilarating look at a family’s refusal to give up on a loved one driven not just by intensity but by adoration as well.

What drives I’m Still Here isn’t just the quest to find a missing loved one over a long period of time, but also the appreciation for when times were good (and not through a strictly nostalgic lens either). Salles includes sequences that are implied to be home footage on sixteen millimeter film which bring us into the Paiva family, feel like we’ve grown up with them and experienced the same joys and successes; no longer are we watching actors on a set. Salles also infuses so much Brazilian culture into this film to honour the very nation that is at odds with itself during the events of I’m Still Here; from sensational, iconic tunes (like chanteuse Gal Costa’s “Acauã”, and psychedelic rock band Os Mutantes’ “Baby”) to stunning images of Rio de Janeiro. It would be easy to just point fingers at a country undergoing a sociopolitical crisis and find the damage done, but Salles does right by Brazil by cherishing — even during a dark era — what makes the nation brilliant.

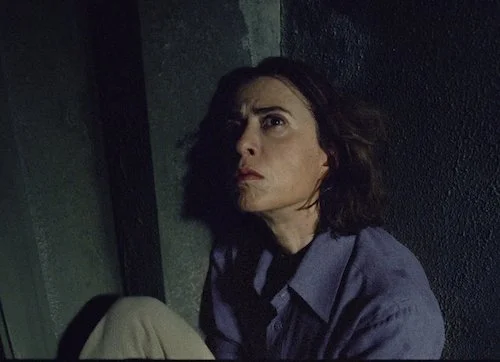

This compels Eunice and her family as well; not only are they fighting to bring their loved one back home, they are aiming to protect the identity of their motherland (one that couldn’t surely take away one of their favourite people without any sign of a possible return in sight). This harmony between anguish and faith can be found not just in I’m Still Here, but in star Torres’ leading performance as well. There is a major reason why her name — one that has been sung for decades by this point — has been often brought up and celebrated during this awards season: Torres is phenomenal. Not only is the beating heart of the film when she seeks to shield her family from the dangers of the world (a tightrope act that sounds easier to do on film than it actually is: many shining beacons in harrowing films come off as phony or delusional, but not Torres), but she is the performance who carries the weight of the desperation felt throughout. Torres is more than just believable: she is unstoppable, delivering a performance for the ages. In fact, she may display the best acting of 2024 in I’m Still Here.

Fernanda Torres is as brilliant as many have declared her to be in I’m Still Here, with a generational performance in an illustrious career.

To call I’m Still Here a dynamic film is an understatement. Any other director trying their hand at finding sentimentality and hope within tragedy would have made a heavy-handed, sappy look at an actual crisis (which, typically, comes off as insensitive). Salles soars with I’m Still Here, though, and the convergence between devastation and assurance creates a heartfelt love letter to a lost life (and, in turn, all of the lives who have been “disappeared” at the hands of political friction). Salles’ return to his Brazilian roots is also a podium to project his appreciation for his homeland in the aforementioned ways, as well as the inclusion of national icons in undeniably fantastic ways. Not only is Torres at her very best here (alongside the always popular Mello), but her mother — that’s right, Montenegro of Central Station fame (amongst many other films, of course) — returns to play Eunice at an older age; her performance is brief but incredible (and I’ll just leave it at that without spoiling as to how).

Once the real footage of the real Paiva family members rolls in during the credits, Salles concludes a commemoration of a family who never gave up no matter the odds; even when others would have stopped, they kept going in ways to at least esteem Rubens by any means necessary. Yes, folks. The hype is real. I’m Still Here is a resplendent motion picture that is full of life as to represent what it means to be worried about livelihoods. A maternal hero is prioritized to help nurture a family, nation, and film crushed by sorrow. To me, the title represents not just Eunice and the rest of the Paiva family’s fortitude but also Rubens’ legacy through their eyes (and, thanks to Salles’ film, the gaze of all viewers). Within I’m Still Here is hefty doses of truth which help any levity from ever feeling artificial; if you want to know what a crowd-pleasing, hopeful-yet-tragic drama feels like without seeming too synthetic (like many Hollywood pictures), here’s your film. I’m Still Here is here to stay, and I think it will ripple through the minds, hearts, and souls of viewers for years to come.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.