Mrs. Miniver

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. Mrs. Miniver is the fifteenth Best Picture winner at the 1942 Academy Awards.

For some reason, the first batch of Best Picture winners had a few films that were hung up on a family experiencing history together. Cavalcade was the first, and most misguided, film to attempt this. Gone With the Wind was a much better experiment. I’m just going to say it. Out of these films that were obsessed with this idea, Mrs. Miniver probably pulls off this notion the best. The biggest reason why is because Mrs. Miniver was not looking backward. The history it was observing was in the making: the early days of World War II. Right in the thick of it. When the world seemed like this time around, we were all going to die. Having a family, and a maternal figure, to sit next to us as hell broke loose was comforting, engaging, and emotional.

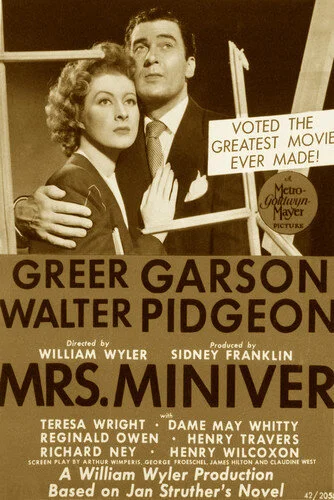

The first (and, yeah I’m stating this now, the best) film by William Wyler to win Best Picture, Mrs. Miniver is centred around Kay Miniver (played exquisitely by Greer Garson). However, the title is cleverly deceptive. Kay is, indeed, a Mrs. Miniver, but the film also represents Carol Miniver (Kay’s daughter-in-law that marries her son during the film), and a prized flower at an annual florist competition. Without spoiling anything, the flower represents stability, new life, and withering death (either by the forces of nature, or at the hand of humanity). Even though we follow mother Kay around, it is imperative to remember every other element designated as “Mrs. Miniver”, because all of these parts are important for the whole.

Kay Miniver is morally stuck on whether or not to help a stranded German fighter pilot.

What also makes Mrs. Miniver the strongest example in this small Best-Picture-Winner-Based-On-A-Family-Experiencing-History-Together category (I won’t have to type that out much longer) is how each scenario takes place in the same contextual vicinity. All of the film is tied to World War II. This means kids being sent to war, other kids stuck at home waiting, and the domestic ecosystems shattered by surprise attacks. A number of Mrs. Miniver’s plot threads barely correlate with one another, outside of who they are happening to, and why they are even happening. Despite this, the film still feels like one unit, and characters are built well enough that all of these vignettes matter.

Mrs. Miniver is also cunning enough to know how to avoid getting bogged down by the Hayes code. It has a good, strong, and Hollywood ending, but that doesn’t hold it back from tossing in some jaw dropping curve balls (even late into the picture). I appreciate that. The film promotes togetherness during crises, but it isn’t senselessly stupid about what a family can accomplish together. It’s the kind of control that elevates Mrs. Miniver amongst its peers. While I prefer The Magnificent Ambersons and Yankee Doodle Dandy from that year’s Best Picture race myself, you can make a strong case as to why Mrs. Miniver deserved its win, and I would completely understand.

The Miniver household trapped during a bombing.

When released in 1942, Mrs. Miniver was immediately deemed an instant classic. Now, I feel like too many people forget it exists. Would I classify it a pinnacle achievement, as if I saw it back in 1942? No, but that doesn’t make it any less worth watching. Sure, back in 1942, Mrs. Miniver provided celluloid faces and thoughts to the biggest scare the world was experiencing. Decades later, it now feels like an interpretation of what could have been our final hour, and its nobility never subsides. As modern filmmakers ponder about climate change and economical horrors, hopefully there is a future that can look back similarly, and understand our mindset. With Mrs. Miniver, the integrity can never be questioned. Its ability to take its then-disturbed audiences very seriously allows it to remain special.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.