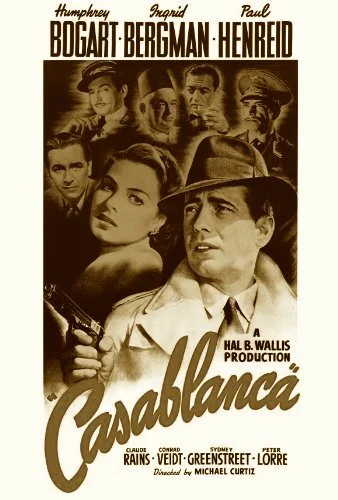

Casablanca

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. Casablanca is the sixteenth Best Picture winner at the 1943 Academy Awards.

It’s finally time to talk Casablanca. This is what the Academy Awards was made for. Sure, I’ve granted some previous winners a perfect rating, but the essence of such a ceremony was made to pick the films that would stand the test of time as unanimous favourites all across the board. I can think of some people that wouldn’t be on-board with my love for Rebecca. I can’t imagine too many cinephiles having major problems with Michael Curtiz’s iconic romantic epic (and likely the best romantic epic to ever be filmed). Citizen Kane lost to How Green Was My Valley. Here, Casablanca won. It did it. A film of this magnitude, and with such an ability to permanently change the face of cinema, was honoured rightfully so.

In order to appreciate how special Casablanca truly is, we have to separate what made it great when it was first released, versus how we feel about it today. Well, remember how Mrs. Miniver held the hands of viewers during their darkest hours (during the harrowing beginnings of World War II)? Well, Casablanca focuses less on the literal sights of war, and more-so on the resonating effects of those impacted at large. We have divided nations, conflicted relationships, and dreams that turn into escape plans. Casablanca takes place in a hideaway den, and immediately all viewers are on the same page. We know why Rick Blaine is in Morocco to some degree, even before we are told specifically why.

The collective singing of “La Marseillaise” is an early, definitive moment of the film.

Casablanca is the strongest romantic epic, because it understands fate perfectly well. Fate is more than just luck. It can be negative as well. Rick had great luck before. He was in love, and his life was ready for him to live. Then it all came crashing down. Unlike The English Patient or Out of Africa, Casablanca puts less focus on the two leads being in a committed relationship, and more on the after effects of a love that turned sour. Having this partnership be a portion of how people were effected during a worldwide crisis is what sells the romance in Casablanca in the first place. Having the film only focus on love, and have historical movements serve as a backdrop is borderline inauthentic. Casablanca exists because of its historical contexts, and any character traits featured are the result of these moments in time.

So, what makes Casablanca powerful today? I think the immediate draw to the film is how quotable it is. You’ve seen it spoofed countless times, but every attempt is usually out of honour for the original work. You see, the film is quotable because the screenplay (by twins Julius and Philip Epstein, and Howard Koch) was one of the earlier examples in Hollywood’s golden age to fully figure out line delivery and narrative advancement through a cinematic lens. “Round up the usual suspects.”: a solid indication of past problems. “Of all the gin joints, in all the towns, in all the world, she walks into mine.”: personified grief, and a reflection of what feels to be a stroke of bad luck. “Here’s looking at you, kid.”: both a term of endearment through one final glance, and an expression for how a future is open due to this very moment. Even the often butchered “Time Goes By” quote works, because of the context everyone felt while watching the film.

Of course, Casablanca was not the first great screenplay in film history, but it has a strong case for being one of the best of this time period (or ever, to be fair). It presents all of its complexities in the form of the in-depth now. All of its history (outside of one flashback sequence) is delivered through fantastic exposition unveiling, or the film’s insinuation that the audience will understand through showing and not telling. You can summarize the film in a short line: a club owner’s haunting past catches up with him, and forces him to face his sorrows in the form of a former lover. That doesn’t explain everything in the film, though. You know what you are getting on the surface, but all of the deeply rooted details, and Crutiz’s ability to keep every defining factor in frame, turns Casablanca into pure lore.

Rick and Ilsa during a flashback sequence in Paris.

So, we have to discuss the love itself, despite it not being the only story of importance in the greater picture. It’s still the central plot line, and the means of capturing all of the conflicts of a world war. Rick and Ilsa grew to adore each other when Ilsa understood herself to be a widow of war. What does someone do when life gets complicated, and nothing is what it seems to be? How do you hurt your partner the least amount? Ilsa finds her own way, and Casablanca contains a subplot of Rick trying to develop his own method.

That leads up to the classic climax: the ultimate form of saying “I love you”, and perhaps one of cinema’s finest cases of such. There’s no typical Hollywood kiss, or triumphant number. There’s only understanding that adoration can be shown in more ways than one, even if it hurts you the most. It’s about delivering the softest blow when a blow has to be dealt. It’s about figuring out how to better someone else, whether it leaves you in the dark or not. Casablanca is a fantastic love story, because it understands that there are so many embodiments that love can take, and not just the typical phoned-in ways to tick off the usual checklists.

Well, the usual suspects have been rounded up.

The love between Rick and Ilsa is entirely symbolic as well. “We’ll always have Paris” is more than just a fleeting memory held between two war-torn lovers. This is a global civilization banding together to try and keep the world together during a war that is breaking it apart. When the French national anthem is sung, it’s to commemorate all of the identities of the world simply as they are. All of these terrors come from the abuse of one’s nationality as an effort to overtake another civilization, and Casablanca projects that notion in full force. It cleverly takes place in a neutral-enough zone in Morocco, so the film doesn’t have a strongly pro-American or pro-English stance, but a universal approach for all viewers of a suffering global society.

Casablanca delves into the various business trades that refugees, fugitives, and immigrants partook in to get by. The film itself has Rick’s nightclub, complete with a bar, music, and gambling. Many subplots include gun running, informants, and the various authoritative figures bestowed onto those that did not want to be seen as betrayers of their country. Most of these positions were not the first choices these people had, but rather the extreme measures taken to survive. Casablanca is all about survival, and tossing hearts into the ring only makes it harder.

Rick and Ilsa finally making complete amends as civilly as possible.

Casablanca resonates for so many different reasons. On the surface, it’s a damn good film. With time, it’s impossible to not watch this film and understand its importance to the greater cinematic whole. Outside of the fantasy-laden flashback sequence (murky effects to make these scenes play in Rick’s mind), every other single element has aged so well. With a great restoration and a proper playback device, if you knew nothing about classic Hollywood and any of the major performers (like who Ingrid Bergman or Humphrey Bogart are), you could swear this felt like a more-contemporary film made to look old. All of its complexities are ahead of their time. When Mrs. Miniver rode through a storm with audiences, Casablanca picked up the pieces of shrapnel that affected the entire world via ripple effects. You hardly see any bits of war in Casablanca. You may barely remember it explicitly as a war film. And yet, that’s part of its magic. It’s not easily definable.

As the ushering-in of a new wave of Hollywood stars, Casablanca is also important. See, Bogart and Bergman played their two lead parts perfectly. Bogart is the damaged Rick: a mumbling man plagued by his past, who hates dealing with the present. Bergman is the jaded Ilsa, who clearly has lost all of her love of life, and is doing what needs to be done to get by. Having both tampered souls face each other not only bettered the film (especially because of how talented both performers are), as it helped change acting overall. During times where Laurence Olivier was bringing theatrical texture to the screen, and Orson Welles was defining how the lens picked up performers, both Bogart and Bergman were establishing the lingering effects of a past. Most of their performances are based on the end results: the back story. We learned all we needed to know just by looking at them dealing with life.

The ending, with the staring into the misty abyss: a lack of light or darkness, but a soothing middle ground during a time of certain death.

Case in point, Casablanca is iconic for countless of ways. Back in 1943, it was a progression of every cinematic element to the next stage. Now, it’s a benchmark for a major turning point in filmmaking, screenwriting and acting (amongst many other facets). Many films have tried to be Casablanca and failed. Instead, these filmmakers should take a note from Curtiz and company, and vow to go off the beaten path to find substance. That’s how oil gets discovered. Instead, the same spot was picked many times since. Even in 2019, Casablanca feels unique, refreshing, and inspiring. You can only pull off a film of this caliber once in a lifetime, and it shows.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.