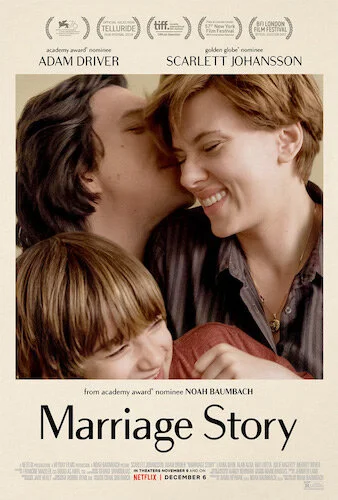

Marriage Story

Never has Noah Baumbach been this good, and that is saying a lot. His goal to shed light on his personal experiences with divorce is not a new mission (see films like The Squid and the Whale, for instance), but he has truly perfected his methods this time around. Marriage Story is so finely written, it rarely feels like a single perspective, like Whale may have been (and that is not a problem by any means). If anything, it feels like dumb fate playing its tricks again. See, Charlie and Nicole Barber start the film off unhappy with one another. We can tell that a separation is imminent. But, Baumbach is more fascinated with the progressions of said divorce through external forces. That makes Marriage Story all the more painful.

From the start, family members and friends — wishing to extend their best interests, mind you — offer forms of advice for their aching friends; this includes legal precautions, which is something the Barbers previously agreed to avoid. One lawyer gets hired by Nicole, which forces Charlie to get his own lawyer, given the right to forfeit possessions and full custody had he not responded. Then, two lawyers are involved, and they get at each other’s throats. Then the legalities get messier, and the Barbers get uglier with each other. All of this, and then some, because of loved ones trying to help through a difficult time. Ouch.

There was a time when the Barbers were in love with each other.

Can you blame these people for trying to help, though? By people, I mean family members concerned about their kin, lawyers trying to help their clients, and friends trying to be reliable. Who wouldn’t want to be there for someone they love during a dark turn? Marriage Story doesn’t put the blame on anyone (just like how the mutual agreement to separate was a democratic choice), rather it just shows that ugly situations are always going to be ugly. There is no way to split a family well. There just isn’t. Baumbach knows this reality too damn well.

So do Scarlett Johansson (who has been divorced herself) and Adam Driver (whose parents divorced). Both performers — I personally feel — never get their dues from the masses, perhaps because of their franchise connections, and the lack of exposure of their strongest capabilities in these wider released films. Either way, both performers have never been better. Johansson is a highly fragile spouse trying to figure out why she was even in this position to begin with; she shakes in agony, bursting to get out of an emotional prison she never knew was bad for her. Driver, on the other hand, is a patient bomb waiting to explode. He made a major mistake, because he felt not doing so would have caused him to fall apart: a fear he keeps trying to prevent the entire film.

Marriage Story uses parallels to spark similarities whilst showing distance between two partners.

With a fine set of performers behind them, Johansson and Driver are completely unstoppable, and they thrive off of each other and their fantastic costars. These include a tough-as-nails Laura Dern, a savage Ray Liotta, a well-meaning Alan Alda, and a perky Julie Hagerty. If Marriage Story isn’t the definitive winner for the Outstanding Performance by a Cast award at the SAGs, then something is unquestionably wrong. Not one single person felt out of place; not even the young Azhy Robertson, who is an emotional, tabula rasa anchor stuck in the middle of a hideous divorce.

It’s easy to see how influenced by Ingmar Bergman Baumbach is in this film (in case the appropriate Scenes From a Marriage reference wasn’t a dead giveaway). With so many visual reflections on Persona, Baumbach channels the idea of a duality in a completely different light here. Nicole and Charlie aren’t two people that think they are one person. They are two severed halves of a matrimonial whole. They are two individuals that are fighting their own battles, which happen to be the exact same fight. However, they have to take on these challenges alone, despite how much they wish to rely on one another to get through this (Charlie’s insistence that Nicole won’t take on certain legal measures, for example).

Memories become nightmares, but the little things in between become nagging reminders.

Baumbach has also been so fascinated by all of the little things that make us human (see, well, every single film he’s ever made), and these have never felt like such a curse like they do in Marriage Story. We are shown countless amounts of habitual rituals that the Barber family partakes in: haircuts at home, Monopoly games, and vices like forgetting to shut lights off or having short tempers. These daily events begin to become the ghosts of a partner’s past, as they haunt Nicole and Charlie for the duration of the film. They plague us as well, each and every single time we quickly remember why each scene is poignant (and, trust me, they all are). This isn’t our crisis, but we feel as though it is.

Starting the film off with two lists of things that each partner loves about the other is the main reason why these chain reactions start (we know they’re aware of each other), but it’s the continuous reflections of these attributes by either party that really hammers in their importance. Revisiting this idea later on in the film becomes an overwhelming moment of power. The notion of having promises in “writing” is important, as it’s an argument that Nicole and Charlie have to use with their lawyers present to prove their own innocence. Well, we have these confessions written down, so there must be some truth to them, right? With Henry slowly learning how to read, letters and scribbles are beginning to form into thoughts and conversations. We discover that the marriage is dissolving, but the love for both partners as human beings will forever remain. That’s why getting tough is so hard. They wanted the marriage to end, not each other to wither away.

The constant battling for the adoration of son Henry is a prevalent theme in Marriage Story.

I’ve had a long hard brainstorm of all the divorce related films I’ve seen, and I must be honest. Marriage Story ranks up there as one of the finest I have ever seen. On the surface, it’s an emotional car crash. Dig deeper, and it’s a literary whirlwind fit for the stage. Drill even deeper, and it’s a poem about the cruelties of life; two people that are so alike aren’t meant for each other. How can life be so backwards? The title isn’t an insinuation that all marriages end in divorce. No. To me, it’s the realization that there is a marriage between two divorcees: a partnership between those separating from each other, whether it be a civil understanding of one another, or a shared devastation between two lone spirits.

At times, Marriage Story felt like it wanted to be Kramer Vs. Kramer, with its fighting for the affection of a alienated child, the bitterness found in the courtroom, and the changes a parent needs to make to make up for a missing partner. It not only succeeded, but it honestly surpasses its inspiration. Marriage Story will remain a sterling example of this subject matter for years to come; if not, it will at least be the opus of Baumbach, Johansson, and Driver’s already-strong careers.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.