The Godfather

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. The Godfather is the forty fifth Best Picture winner at the 1972 Academy Awards.

“I believe in America”.

The opening line to Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather could not be more fitting. In this gangster epic, the milk and honey of the American dream gets analyzed through and through, with all forms of pursuance included. This is the story of the suffering doing what they can to survive, and the elite doing anything to maintain their power. We watch a mob family tree and all of its extended branches, but we’re really learning about the American way. How is it that a mafia family can be so connective with varying audiences over a near-fifty-year span? Corruption runs through our systems, and Coppola’s adaptation of Mario Puzo’s novel is a gang-related-metaphor for the problems within society.

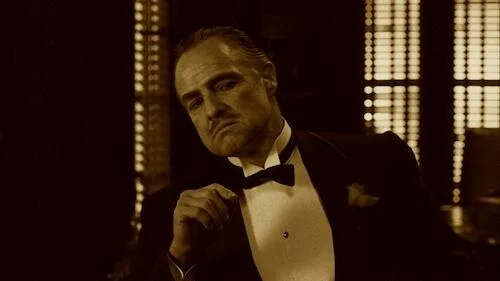

So many years later, it feels safe to say that The Godfather is a one-of-a-kind film (well, aside from The Godfather Part II, which we will review in a few days time). Like Pet Sounds for music, or The Great Gatsby for literature, The Godfather is an undeniable turning point in an American medium. The sepia tinged images, the haunting score by Nino Rota, the highly modern editing (mainly because most films tried to be The Godfather after it was released), and then some. Everything about this film was in tip top shape. It expressed enough aesthetically to appeal to the New Hollywood movement, and it pushed itself narratively to improve upon the ever-expanding ways of cinematic storytelling. It isn’t difficult to see why The Godfather has such a following. It set a tone when released, and has felt modern ever since for younger audiences.

The opening act is a lengthy observation of the Corleone family in the form of a wedding.

The long wedding opening (not The Deer Hunter long, but long) is a strong introduction to the Corleone family, with Vito acting as the patriarchal head of the family, the tight-knit siblings interacting with one another, and Michael’s arrival showcasing his distancing from his group. That’s when we figure out that this is Michael Corleone’s story. If you’re under the apprehension that this is a solo Marlon Brando effort before you watch this film, you are sorely mistaken. The cast is arguably the strongest in film history, first off. Secondly, while Vito Corleone’s tale is an important element of the entire narrative, this is more or less a study of a son that wanted nothing to do with a crime family, becoming the strongest driving force of said family.

Michael’s development is the greatest in film. Between this first part and Part II, you will witness the scariest corrosion of a decent man in slow burning fashion (we don’t like discussing Part III here). Alas, this is only Part I. This is the dousing of Michael’s head in the baptism chamber of the devil. These are all of the events that turn a man mad, especially when it comes to the downfall of his family. The Corleones try to practice the less sleazy side of mafioso legalities, but the times are changing, and they are losing their edge. As an outsider to how the family operates, Michael takes a different approach; an unorthodox one, but a unique one. With that, he immediately assumes power; not through heritage alone, but with the angst created by him not wanting to be here in the first place.

The Godfather is the tale of an untainted son’s slow descent into being the most dangerous man in America.

Part II is the followup to Michael’s transmogrification, but Part I is all about the countless forms of trauma that breaks a morally conscious man. In the same way the mafia makes irrefutable offers, the mafia also makes a family member’s connection impossible to ignore. Michael has to assume his position. He not only does so, but he begins to become the perfect man for the job (much to his chagrin). What is interesting is how unlike his father Michael is. Vito has to dip his toes in the pools of sin sometimes, sure, but he regards himself as a father figure to all of his children (blood related or not). For Michael, everything becomes business. He lost his family ties a long time ago. This is all just money and power moves.

If you focus on Vito’s side of the story in this first part, you see a man who has tried to distance himself with the uglier sides of crime, and remain a figure of hope for those close to him. Of course, he has to fight through some major burdens (a focal point of The Godfather), and it only makes his position even more difficult to maintain. After seeing Part II, I feel even worse for Vito: a man that became the face of danger, only to try and revert back to being a family man that finds value in love. It seems like a futile mission, but one that Vito is so close to achieving. Then, comes this film: the darkest chapter of his life since he became the don of his powerful family. We’re there to see it. So is Michael.

Vito Corleone, after years and years of sustaining his family as a family, and not simply a group of like minded criminals.

Through the expert filmmaking, tension is created for all of The Godfather’s runtime. The long wedding is an establishing sequence, but it also makes you wonder “what happens next?”. Then we have some textbook scenes that show the finesse of the finest levels of filmmaking. The first is the restaurant meetup: a strong case for the perfect scene in all of cinema. The switching from English to Italian has your eyes darting around the screen. The slow zoom onto Michael’s face is an extra level of uneasiness. When the nearby train begins to override the sound of the restaurant, that’s when you feel completely unsafe, and as though anything can happen. The allowance of the scene to overtake the scenario is a certain gift Coppola once had in his heyday, and this is such a case where his talents are in full effect.

Then, there is the baptism: the turning of desecration into a religious ritual. Combining the church organ and the hymns of a priest ushering in a new life into the Catholic faith, with images of calculated murder is the work of flawless juxtaposition; the kind of risk arthouse filmmakers take, being done with pure conventional (yet still bold) ease here. To signify the end of various families, and the rebirth of the Corleones renders the baptism sequence another staple of the Godfather series. If there was ever a turning point for Michael, it was the day he turned the birth of Jesus Christ’s newest follower into the bloodbath of his various children.

Michael ends the film a completely changed man, with room to change even more (for the sequel).

There are many ways to enjoy The Godfather. Its dialogue (the countless amounts of quotes). The shocking violence (easily the most violent Best Picture winner at this point). The perfect casting. The golden imagery. On a first watch, everything will stick out at you. It’s when you become obsessive with Michael’s acceptance of his fate that The Godfather truly becomes a tragedy for the ages. Not many films with this amount of clout are completely, justifiably rated. The Godfather is a peak level of filmmaking, with a lack of care for how the future of cinema would end up. Its confidence allowed it to create its own rules, perfect the actual guidebook on how to make movies, and ensure enough staying power that it remains a pinnacle film; for gangster flicks, for New Hollywood cinema, for award winners, and, for some, for all time.

Having said all of this, I personally prefer The Godfather Part II. Stay tuned.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.