The Sting

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. The Sting is the forty sixth Best Picture winner at the 1973 Academy Awards.

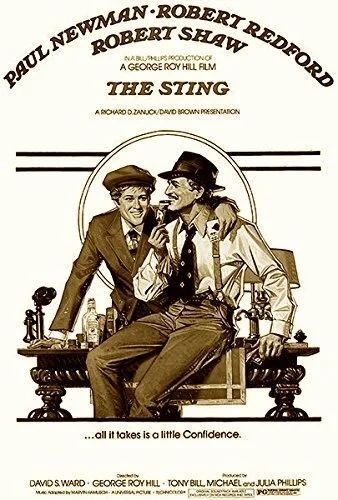

In the late ‘60s, George Roy Hill paired up Paul Newman and Robert Redford in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid: a traditionalist western to combat the rise of the spaghetti sort. It was a superb time, and an indication of pure chemistry between the two leads and the filmmaker. It wasn’t much of a long wait until all three partners bested this previous effort with The Sting. Similarly, this film was an observation of older America (this time the ‘30s, during the Great Depression) with a modern lens. Hill never goes full New Hollywood in any way (a break from the previous couple of Best Picture winners), outside of maybe how edgy the film feels. Otherwise, this is straight up cinematic fundamentals, and it all starts with the flawless screenplay.

David S. Ward’s writing is a thorn bush of plot threads, with so much calamity happening at once. The biggest appeal with The Sting is trying to keep up, especially since the bulk of the story is based on how con artists trick each other to get one step ahead. With a name like The Sting, you’re just waiting for that moment where everything slips; who’s going to be the person that gets hit the most? With the narrative divided into chapters, we arrive at “The Sting” as the final act. This is it. This is what all of the build up was for. The coup-de-grace couldn’t have been sweeter. We expect characters to be treated like idiots, and yet we are the film’s biggest victims. We get so misled, and it’s the most fun you’ll have feeling stupid.

Most of the film comes from Kelly’s perspective, especially since he tries to one-up Shaw.

To swing an audience, we need some charm. Redford as Kelly is imperfect, but you’re curious to see what such a gutsy guy is capable of. You don’t want to see a heartthrob, morally conscious gentleman get in the line of fire. This dude? Sure. Why not. In Butch Cassidy, Redford and Newman were more of a pair. Here, they’re merely dealing with each other to get their own selfish desires. Newman as Shaw is part inspiration to Kelly, and part competition. Who better to fool than the greatest conman there is? Since most of the film comes from Kelly’s perspective, you are often left wondering just what Shaw is up to. You know there are lies thrown into the mix of what he says, but just how much of his claims are actually factual?

The Great Depression setting gives this heist thriller a bit of a kick. You can understand why people were driven to such depraved acts, like compulsive conning, as a means to get by. It’s also a solid excuse to toss in some ragtime tunes (Marvin Hamlisch’s score still gets referenced, as do the inclusions of popular tunes, particularly by Scott Joplin), and snappy retro dialogue. The immersion of these characters in the ‘30s takes a bit of a backseat to the rapid fire screenplay, but every little detail is there. If you so choose to look past the script, you will find the world building you so desire. Despite the film feeling modern (in the ‘70s, and even now), the travelling back to an earlier America is highly successful, thanks to some convincing sets, costuming, and personifications by every performer.

No matter how close Kelly and Shaw get, you never know just how much they trust one another.

If you don’t get sucked into the environment, Ward will dizzy you with his screenplay. Trying to navigate every single individual objective makes the first viewing of The Sting a ride on a merry-go-round: a trip that goes in circles, but never leaves the same spot. The glory is revisiting this film when you learn just what is happening at every time. It’s almost futile to try and out-guess the film; sit back, and let it whisk you away. That isn’t to imply that The Sting is thoughtless. Rather, I’m suggesting that you should reserve your brain power for every subsequent viewing. With screwball elements, The Sting fancies itself a ball of confusion: the slapping of minds and egos rather than sticks.

Like a game of cards, The Sting is the endurance test to see just what play the film is going to dish out. The performances of the actors are simply performances. The wordplay is full of hidden motives. The editing is just the masking of illusions. In the same way that film is the ultimate form of accepting lies that artists are dishing out at us, The Sting is the ultimate cinematic fabrication: the yanking of you by the neck the entire time. On immediate impact, it’s clear as day to see why the film was a smash hit. When other films around this time were trying to push cinematic boundaries, The Sting got away with the bare essentials, and it fooled every single viewer since.

The notion of card play is important, since it’s this kind of deception that fuels The Sting.

What is strange is how little there is to discuss with The Sting. If not to prevent spoilers, there’s also so little of what’s so great to gush about (in the sense that The String is brilliant in all of its few missions). There isn’t anything too deep here: it’s simply a handful of swindlers trying to survive an economic crisis. The characters mostly seem to have similar directives, and there isn’t any poignant statement about the world or society (outside of greed’s control of people, maybe). Sometimes, a damn good time is a damn good time. The Sting is some of the most film a film can provide, and most of it is at your expense. Glorious.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.