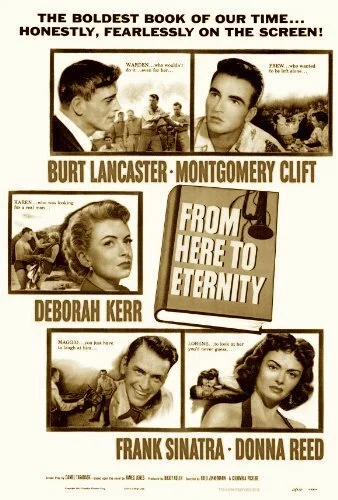

From Here to Eternity

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. From Here to Eternity is the twenty sixth Best Picture winner at the 1953 Academy Awards.

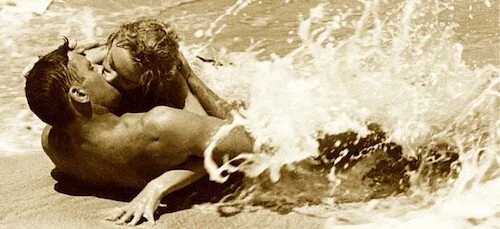

So, Fred Zinnemann was robbed of his Best Picture win for High Noon: a conflicted Western that takes place in real time, and features the many tensions between various groupings of people. He didn’t have to wait too long, as his next effort ended up taking the twenty sixth Academy Awards by the neck. From Here to Eternity was a huge sensation back in 1953, and its extreme depictions of passion still resonate today. Out of all of the romantic epics that have ever been made (or have won Best Picture), I wouldn’t say Eternity is the best, but it definitely feels less kitschy than some of the other entries. The film never feels subservient to its love plot line. Romance exists amongst everything else, on what feels like an equal playing field.

Perhaps that is also part of the reason why Eternity has a decent rating, and not a glowing one. It darts its head around trying to appease its three main story lines (three different American soldiers, stationed in Hawaii). I wouldn’t say any of these plot threads get neglected, but all three feel like stories that could have been served up as something even greater. It’s a unique experience, because Eternity acts somewhat like a holistic whole, rather than a combination of narratives. These stories may only go so far in their own shoes, but everything kind of works together, creating an identifiable mosaic depicting life in a barracks, and facing abrupt horrors as they come.

The iconic beach kiss shot, which has perhaps transcended the film’s own legacy to this day.

So, much of the film is invested in the downtime and daily affairs of the three leads, played by Burt Lancaster, Montgomery Clift, and Frank Sinatra (can a cast be any more swoon worthy?). We see their romantic partners, friends, and enemies, frolic amongst them; these include Deborah Kerr, Donna Reed, Ernest Borgnine, Jack Warden, George Reeves and more. This star studded affair punctuates all of the casual moments of the film, since we have performing experts that know how to boost nay moment. These include chit chats, dates, and fights.

Of course, everything is leading up to the ending: the shock of the attacks on Pearl Harbour. Eternity does a strong job of creating some sort of character bases, even if the storylines sometimes feel like they aren’t going anywhere. Even the background characters seem to have some sort of a connection with you, because you can see the same faces populate various moments. These feel like real, breathing people. Having them go through an ambush instils the kind of shock I believe Zinnemann wanted you to have. Eternity is secretly a war film, and we should have known the very first second we arrived at the barracks.

The Pearl Harbour sequence is a well choreographed display of technical finesse, and easily the strongest moment of the film.

Whether you’re being swept off your feet, wanting to chill with Mr. Old Blue Eyes himself, or are on the edge of your seat during the climax, From Here to Eternity is proven to be an engaging film. While its story telling feels a little abandoned, it’s easy to see how this film could have left its mark on a nation when released. It’s a well shot mood piece with all of its emotions on its sleeves. Comparing this work to more frigid war films (or, specifically, anti-war films) can maybe give you a better picture. How many war films of its time felt like this? Eternity isn’t bashing a message over your head, nor is it a super patriotic glorification of Americans in battle. It’s just life, as if it were transferred onto a war zone. It’s a nice change of pace for the ‘50s.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.