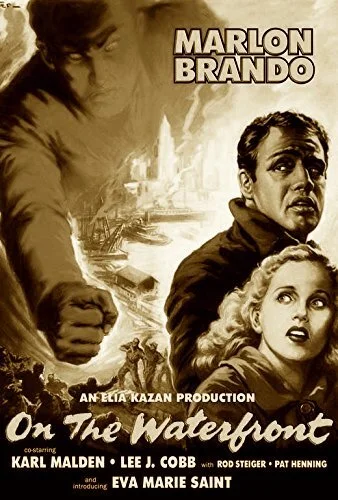

On the Waterfront

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. On the Waterfront is the twenty seventh Best Picture winner at the 1954 Academy Awards.

Seven years before On the Waterfront, Elia Kazan brought Gentleman's Agreement into the world. It was a commentary on how a marginalized group (the Jewish community) was experiencing bigotry amongst social circles and work environments after World War II. It was a strong film, but there was slight room for improvement. Well, Kazan clearly knew where his previous film went wrong (an unsure ending, and the ability to dive even deeper into its study). On the Waterfront is similarly an analysis on a maligned community (blue collared workers under the thumbs of the elite and the criminal underground), and its social coverage is kilometres wider.

The first fantastic readjustment is focusing on multiple key figures, rather than rally behind one sole individual. The film pivots behind three main characters. There's Father Barry (Karl Malden), who tries to hold the fort between communities within his church; he often is the face people turn to, to discuss injustices within the neighbourhood. We have Edie (Eva Marie Saint) whose brother was murdered, and she demands answers as to why (as well as why nothing is being done about it). Then, of course, we have Marlon Brando's Terry: a self confessed "bum" stuck working on a dock after he felt forced to throw a fight during his boxing career.

Father Barry feels like an outsider trying to analyze the struggles of his city.

Waterfront is paced by the loaded intentions of others: mob bosses leaning on their connections, the angered questioning the church, and workers rebelling against their bosses (as much as they can, at least). When Edie and Terry cross paths, the connection makes perfect sense; their calmness with one another stands out from the rest of the film. When Terry tends to his pigeons, there's a serenity you can feel in your bones. You truly understand why a church, a rooftop, or a swing set become sanctuaries to these characters. We all need our special places to hide from society's chaos.

The story was all about refining how tales were previously told. We had narrative connections that all play out sensibly, feel authentic, and even invigorate specific emotions out of us (maybe even better than many films that came out around this time). If the story was refined, then the acting was reinvented. Brando's signature performance is self explanatory. His method approach, as well as his implementation of "thoughts", turned Terry into a character that was more defined than any that came before him. It's a silly oversight, but Brando made sure to acknowledge that real people don't just spew out lines on command. We all have mental blips, or need a second to figure out what exactly we are feeling. Even if previous performers paused, Brando made these pauses their own punctuation points. Every single word has a different inflection, and reason behind it. It's truly one of the most intricate performances you will ever see.

Terry and Edie bonding amongst the chaos.

However, we absolutely cannot forget the other major players, who also serve up their own individual cinematic grand slams. Marie Saint was brilliant for a newcomer, and she takes a hold on every single scene with complete assurance. I'd go as far to say that she even holds her own against Brando in every instance. Malden -- always a solid actor -- delivers his best performance as a conflicted priest trying to make sense of the miasma around him through his faith. Lee J. Cobb is a ruthless boss with criminal ties, whose toxicity rules the entire film (and is guaranteed to instill such anger within you). Rod Steiger plays Terry's brother, who is split between his new life, and his family that he left behind. Waterfront boasts one of the strongest casts you will find in this era.

Johnny Friendly flexing his muscles against Terry.

I also love how Waterfront never pretends to know exactly what life's answers are (aside from the dangers of trying to go big through the mob). It contains individual resolutions for each character, and it's up to you to discern who you feel is taking the proper paths. Gentleman's Agreement situates a specific dilemma. Waterfront bottles up an entire universe of pondering. It's a daring risk, but it pays off so well.

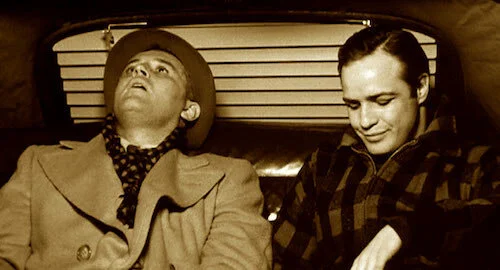

Terry and his brother Charlie reflecting on the past mistakes that led them to this position.

On the Waterfront is a near-flawless tackling of a mindset. It remains as thrilling as it was on release, because it knows how to pertain to each and every individual viewer on a personal level. We've all damned ourselves by "throwing a fight", with varying consequences. We can all acknowledge the many imperfections of society's political infrastructure; some seem to improve, and others only get worse. Elia Kazan may not have know that he had an immediate classic on his hands, because he sought after trying to capture a city's clutter, and the zen found within the hell. He succeeded, and On the Waterfront remains an emotional roller coaster that never lets up.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.