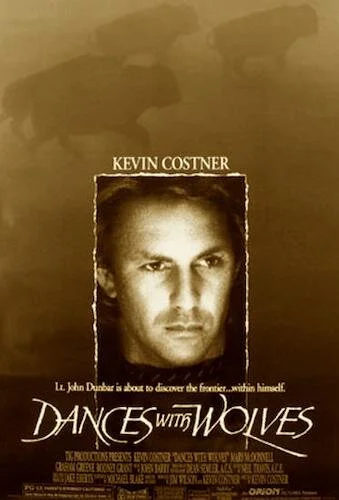

Dances With Wolves

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. Dances With Wolves is the sixty third Best Picture winner at the 1990 Academy Awards.

Believe it or not, Dances With Wolves is only the second western film to win Best Picture (after the dreadful Cimarron). That’s nearly sixty years of a wait. The entire spaghetti western movement was leapfrogged, and the tail end of the classic western era was never wrapped up as nicely as it could have been (I’m still bitter about the whole High Noon fiasco). Maybe as a sentiment to congratulate Dances With Wolves with ushering in the new wave of western cinema, this very film was awarded. It may have also been an act of avoidance to skip Goodfellas from being awarded (the second of two Martin Scorsese features to still be lauded as the Best Picture winners that never were).

Dances With Wolves came at the perfect time. Kevin Costner clearly saw the sentimentality that Hollywood was obsessed with for the last number of years, and decided to fling nostalgia into the mix. Unlike Unforgiven two years later (which spins the western genre on its head), Dances With Wolves is as much of an homage as it can be. Perhaps with some better political correctness to fit the modern age (outside of still slipping into white saviour territory), Dances With Wolves hardly feels like the guiltiest western to put on. It’s in a bizarre strip of its genre’s history, where it doesn’t quite fit with the ways of neo westerns and how much they shape shift the genre, and yet it’s arguably one of the major films to contribute to this moment in time. How can a film be revisionist without much revising?

Dances with Wolves involves Lt. Dunbar’s integration with the Sioux tribe.

Wolves experiences many faults, and they mostly have to do with historical accuracy and accidental distastefulness. Sioux members are given the wrong dialects to speak, and annunciations are reportedly way off. A lot of customs aren’t exactly as they should be, either. All of this, surrounding the film’s focus on the lead character (Lt. Dunbar) is a bad look, particularly because of the insinuation created between a filmmaker and the narrative. However, with that in mind, that could also be why Wolves was more beloved when released. Like Dunbar, Costner’s work showcases an effort to understand a culture he is deeply interested in. You can tell he cares more about the Sioux Nation, than a lot of filmmakers do with whichever tribe they are covering. Making a great western was an obvious focus, but not the sole focus.

Because of that honesty, Wolves is not a hopeless experience. Slip past the narrative concerns, and the major inaccuracies, and you find an actor-turned-filmmaker not just wanting to bring back a dead genre, but to do it right this time. Details may be poorly researched, but nothing here feels strictly exploitational. The way Wolves is shot and structured is with tons of heart. Visually, it’s a graceful film. Its foundation is fairly sturdy, especially the near-four hour version. Outside of some romantic conventions and the previously discusses faux-pas, Wolves is a sincere effort, with enough good-stuff you may not see coming (if you have been caught up in the bashings the film has received over the years).

The relationship between Lt. Dunbar and Stands With a Fist is an important plot thread in the film.

Ignore the reputation Dances With Wolves has built up (Avatar feels like part of that resurgence), and you may find a classic-feeling western with earnest notions, and passionate tributes. While not the most important film to give the genre a whole new sheen, Wolves is certainly pivotal with the genre sparking much interest at all. Musicals continue to feel niche some years. Screwball comedies don’t really get picked up at all. The western was honestly on its way to certain, irreversible death. We needed just one film to remind us how endless the 1800 plains are, how well choreographed a good old fashioned horseback battle sequence could be, and how timely a stripped down minimalist story could be. Wolves embodies all of those points, because Costner looked back on a beloved genre with a modern gaze. While imperfect, Wolves is a strong effort whose beauty and fervor presents an early ‘90s poem to the golden years of Hollywood. With this recreation out of the way, cinema was ready to flip the genre, and for that we have Costner’s ice breaker to thank.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.