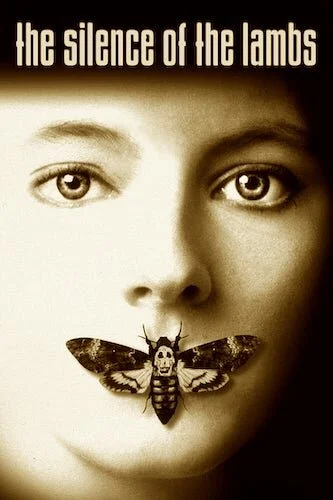

The Silence of the Lambs

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. The Silence of the Lambs is the sixty forth Best Picture winner at the 1991 Academy Awards.

The Silence of the Lambs is somewhat of an Academy Awards miracle. Here is this horror film -- the only one to ever win Best Picture -- released in February (the worst month for any form of an awards season push). It was a major leap from anything the Academy awarded the best film of the year in many years. Not since The Deer Hunter had a Best Picture been this vicious. Yet, here we are. It won the top five awards (Best Picture, Director, Actor, Actress, Screenplay), is touted as a horror/thriller masterpiece, and we haven't looked back since.

The Silence of the Lambs had to be a damn good film to pull off all of this, and it's easy to see that it's more than that. Jonathan Demme was well versed in music videos and concert films (Stop Making Sense being a pinnacle moment in the history of concert films), and he approaches much of Lambs in a similar way. The choreography of horror works similarly to a dance. There are fluid moments used to create passive tension, and jump scares intended to punctuate scenes. Like a videotaped routine, Lambs becomes a thriller symphony that drills itself down deep in your brain. Clarice Starling proves her boldness and mental courage throughout Lambs, but she often gets tested. So do we. We feel her turmoil.

We follow Clarice Starling through her biggest tests as an FBI agent in training.

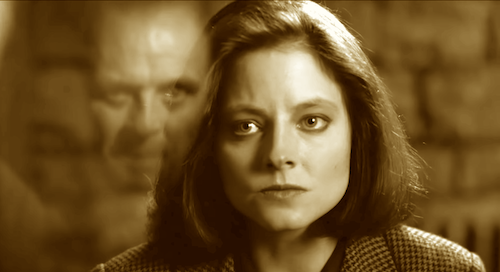

Lambs wastes no time revealing its grittiness. Starling has to find out more about a serial killer (Buffalo Bill) through the incarcerated Dr. Hannibal Lecter: a cannibal psychiatrist that sinks his hands into the minds of his patients, literally and figuratively. Of course this is Hannibal’s film, if pop culture has told us anything. Except, it truly isn’t. I was astounded when I watched Lambs for the first time, for two reasons. Firstly, Hannibal is only in the film for twenty minutes or less. Secondly, he felt like he was in the film for an hour and a half. Anthony Hopkins’ evil ways hypnotize you. His presence never leaves. He feels like he is a part of the entire trip, with his glare etched in the back of your mind (even in scenes that don’t pertain to him at all).

Despite that piece of performance magic, we have a commanding performance by Jodie Foster as Starling that, shockingly, doesn’t get talked about enough. She starts the film hard as nails, trying to make her way into the FBI. Through her confrontations with Hannibal, she maintains her strength but displaces her self guilt. We learn more about her as a person, while she sinks lower into the depths of humanity, and learns just how sick people truly can be. The more she develops, the more society shatters. She’s not a cardboard cut out of a hero, either. She experiences fear head on, only she is able to move ahead despite the chokehold horror has on her. It’s a dazzling performance pulled off by Foster.

Despite not being in the film much, Hopkins’ Hannibal manages to remain the most memorable moments of Lambs.

Starling has to find the truth through Hannibal’s riddles and psychological jabs, as she has to confront her own demons in order for him to help in any way. Is he a sadist trying to make her crumble, or just a doctor trying to help someone in his own twisted way? Perhaps both. The relationship between these two is at Lambs’ very core, as both people are broken and individualistic in a world of evil (even though Hannibal caters to this universe). When Starling revisits her most traumatic moment as a child (the slaughtering of screaming lambs), she realizes why she rejects the world around her. Hannibal is willing to help those that help themselves, maybe as a slight sign of the good he is capable of despite his monstrous ways.

Lambs is not the first artistic horror film, but it’s a strong example of a Hollywood film that indulges in the poetic side of cinema. From the way corpses are displayed, to the use of camera zooms and pans to establish chaos or power, Lambs is mightily orchestrated. If you read the film on a literary level, you get an astounding crime thriller, with twists and turns at ever corner. If you try to avoid the reality of Lambs and look elsewhere, you will feel like you are going insane. Starling looks like she is behind bars during some cuts. Corpses look like Rorschach tests. Pop songs turn into demon melodies, because of their synthetic ways (I’m thinking particularly about “Goodbye Horses” here). What you know begins to shift. You’re either stuck with the disturbing story, or the unreliable aesthetics. There is no turning back, Clarice.

Even the more disturbing images in Lambs are turned into profound art.

The rest of the film — outside of Starling trying to make a name for herself in a sexist field, and cooperating with Hannibal to get further in her case — is the case subject Buffalo Bill. We sit in the bottom of a dry well with the kidnapped Catherine, who is being held to eventually be murdered and turned into a part of a skin outfit. Bill is a great foil for Hannibal, because you’re watching someone with absolutely zero remorse run rampant. As bad of a person as Hannibal is, he isn’t Buffalo Bill. Of course, much controversy has steadily floated around since Lambs was released until now, surrounding Buffalo Bill’s negative depiction of the transgender community. I can easily see why, even though I read the character as a psychopath that happens to be queer. Still, having a major character that’s transgender be Buffalo Bill in a time when the LGBTQ community still wasn’t getting proper respect in the majority of mainstream films is understandably frustrating. To have The Crying Game come out a year later and reiterate a group of people as a villain or a narrative device only furthers this justifiable concern.

Nonetheless, Buffalo Bill is frightening, and we as the audience know that more than most of the characters (outside of his captives) first hand. When Lambs spirals down into its climactic moments, we feel like we are on a roller coaster, about to take a major dip. The remainder of the film is a series of loops and sharp turns, and you just want the ride to be finished, because you cannot imagine how much further you can let something else control your every movement. Demme’s music filmmaking experience comes in handy here, with one of horror cinema’s definitive moments. Moths are flying around. Music is blaring. Cameras dip between fixed structures. All is dark. Once the lights go completely off, and we view Starling through Buffalo Bill’s eyes (via night-vision), Lambs becomes the ultimate test in thriller flexibility. How much can an audience take? We’ve made it to this moment, but how do we get out?

The climax of Lambs, night vision and all, is a masterful sequence within horror cinema.

With a final twist at the bitter end acting as a reminder that evil will always linger when good happens in the world, The Silence of the Lambs eases you back into society shaken up, tormented, and cold. If Lambs was only a frigid experience, it would be a stunning exercise in nihilistic damnation. Instead, Jonathan Demme uses the opportunity to not submit himself or the film to complete horror conventions. Adding a pinch of mainstream appeal (the music, the big names) and a dash of arthouse mentality (the cinematography, the shot execution) turns Lambs into a memorable experience for all. As vile as it may be at times, it is made from a place of complete and utter dedication and concern.

Surprisingly, Lambs was never made to solely shock audiences. It just so happens to do so. Lambs is just trying to show the complete catharsis of Clarice Starling. She is a woman objectified by men in her field. She is an agent-to-be being conned by her superiors. She is a person tossed into the darkest corridors of the world. She is a lamb set free from the flock of sheep that were killed en masse, and able to fend for herself. She overcomes all of the tribulations by accepting humanity’s inevitable monstrosities (in the form of Hannibal Lecter), her own capabilities as a person undermined for many pathetic reasons, and that child that was forever changed by the worst experience of her youth finally moving forward.

Starling facing Hannibal in his cell; a metaphor for the lingering impact of the psychopath.

That’s why The Silence of the Lambs has been the only horror to win Best Picture. The Academy is far from perfect, and they are very set in their ways (if this project hasn’t already shown you that). They rarely even acknowledge horror films. What do The Exorcist, Jaws, The Sixth Sense, Black Swan, and Get Out have in common? They are far from your ordinary horror film, and most of them carry some sort of artistic edge or a major piece of commentary (aside from The Sixth Sense, but that’s just me; I’m in the minority and don’t really care for it all that much). The Silence of the Lambs was indisputably the film of 1991.

It’s almost as if the remaining nominees weren’t major threats at all. Bugsy was the only strong contender, but it isn’t better than Lambs. The Prince of Tides is okay, and JFK is good but not perfect. The Academy used this opportunity to nominate the first animated film ever: The Beauty and The Beast. This wasn’t to imply that the film had any chance of winning, but rather the opposite. If Lambs was impossible to stop, why can’t the Academy honour other trailblazing films in some sort of way? Lambs wasn’t stopped. It won the major five awards, despite everything stacked up against it. The Academy isn’t always right, but sometimes it does set a tone by predicting the legacy of a handful of films. The Silence of the Lambs is so mesmerizing and engulfing in virtually every way. It’s futile trying to deny it simply because of its genre typecasting. It remains a staple in the genre, and easily one of the finest horror thrillers ever made.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.