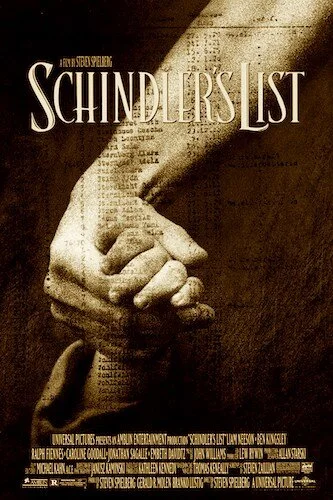

Schindler's List

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. Schindler’s List is the sixty sixth Best Picture winner at the 1993 Academy Awards.

Steven Spielberg gets a bad reputation for his over indulgence of schmaltz and old Hollywood ways. Even though this is the same guy behind irreverent works like Jaws or Close Encounters of the Third Kind, he has more than enough films under his belt that feel too safe, orchestrated, or non threatening. The rights for Schindler’s List were passed around, and Spielberg himself didn’t feel quite right making the film. This would be a far more sensitive work than what he was used to. Well, enough people convinced him, ranging from associate filmmakers to Robin Williams (who was Spielberg’s go-to for comedic relief during the shoot). He began to feel it was his duty, aside from the fact that the film would likely be poorly received. He also refused to have a salary attached to this, likening the wage as “blood money” earned on the backs of the millions killed during the Holocaust.

Twenty six years later, and Schindler’s List is unquestionably the greatest work Spielberg ever made. Aside from the ending revelation made by Oskar Schindler, and maybe the documentary footage to close the film out, absolutely nothing here feels typical Spielbergian. The violence is almost a little too real; even though there are much scarier films, something about the acts of hatred in Schindler’s List still cause me to jump a little bit more, maybe because of their detailed accuracy for an early ‘90s film. The actual filmmaking feels more world cinema influenced than Hollywood, with many moments reminding me of a work like The Battle of Algiers more than a Great Escape, per se.

Schindler’s change-of-heart, and shifting relationship with Itzhak Stern is at the core of the film.

The above-three-hour-length allows Schindler’s List to grant the titular industrialist enough time to perform a change-of-heart for the ages. His first scene, Oskar Schindler sits in the back of a party, with guests wondering who this looming shadow is. By the end of this sequence, new guests ask who this life of the party is, with new friends basically asking how they don’t know who Oskar Schindler is. He had a charisma that could win anyone over, despite his many faults (including compulsive adultery). He focused on profit more than anything else. He hired good looking secretaries before any qualified candidates. He was a member of the Nazi Party, and was able to get by scar-free during contemporary history’s most hideous blemish.

His transition into an important figure in the saving of over one thousand Jews wasn’t instant. You see all of the organic phases that render Schindler a realistic character, better benefiting the true story, rather than glamorizing it. Even in the face of death, Schindler has his priorities skewed. He learns his factory has become a “haven” for Jews to hide in, and he is furious. He cares more about his factory closing, than these lives being spared. That’s the importance of the little girl in the red coat: one of the very few instances of colour found in this black and white feature. That’s the recognizable face that Schindler seems to keep noticing. It’s easier to dismiss the slaughtering of countless innocent people when you view this as a statistic. When you actually apply the life-and-death of a helpless child as one such case amongst many, the severity becomes much larger. For Schindler, this was a wake up call. This was one life that affected him. That’s when he realizes that this was only just one life amongst many. The impact was felt. Millions changes from a word to a travesty.

The girl in the red coat has become an important symbol of the Holocaust, and for Schindler’s List as a film.

For our sake as viewers, we get a few similar chances of our own to dive deeply into this narrative, and soak in the full effect. We have lead characters (Schindler, accountant Itzhak Stern, SS monster Amon Göth), that carry a bulk of the film on their backs. We also get a significant amount of time devoted to various citizens experiencing each and every step of captivity, starvation, and torture. These are a number of Jews that ultimately get sent to Auschwitz; without spoiling, they carry a specific significance as well, one that will bowl you over with emotion. Getting these opportunities to get to know these real people is an absolute gift by screenwriter Steven Zaillia, because it humanizes an event that many other storytellers would use as the moment of shock.

These characters are shot in a way that is meant to somewhat mimic cinema verite (outside of some obvious indications otherwise, including cuts). We feel intrusive, spying on these people during their darkest hours. First, they have to move into the Kraków Ghetto of Poland, and there is barely any space for them to breath. Then, more rights are stripped, they are forced to move continuously, and additional freedoms are removed. Everything gets worse, until that eventual word slowly creeps onto the screen: Auschwitz. If title cards or subtitles could be ranked, this is one of the most affective in film history. The chills I still get, even though I have seen Schindler’s List enough times to know what happens. I still feel like this is a realization, and there’s no way to stop what I am seeing.

The focusing on specific Jewish civilians during the Holocaust is one element that renders Schindler’s List in a league of its own.

As referenced earlier, the detailed scenes of horror are still difficult to endure. With the application of identities to many of these people, you feel as though you have taken part as a bystander during the final seconds of many lives that are cut short. Whether this includes a raid showered in bullets, a worker murdered for doing her job correctly, or the revelation that snow is actually the floating ashes from a mass grave, Schindler’s List implores you to really see just how much went down. I haven’t even scratched the surface of the many twisted forms of punishment that take place in the film; the worst for me is the truckloads of children that think they’re going on an adventure, and their mothers sprinting after them in desperation.

At the forefront of these civilian characters is that of Helen Hirsch: a captured Jew that is turned into a housemaid by Göth. I don’t even know where to begin with the abuse she faces. This underrated performance by Embeth Davidtz allows the scenario to dictate a scene, rather than her response to it, turning Hirsch into a truly devastating character in all of cinema. She replicates the position many Jews found themselves in: either accept what is happening, because you are still more safe as an employee to a Nazi than you would be otherwise, or be killed for opposing. The character also becomes the unveiling of Göth’s worst tendencies, just when you didn’t think he could be any worse.

Helen Hirsch as the object of affection and despise for Amon Göth.

Göth is a performance somersault by Ralph Fiennes, who never tries to make you feel like you have to like this monster (thank goodness), and yet he is still able to make you figure out how brainwashing leads someone into becoming this disgusting. There is one point where he seems to want to change, after discussing the act of pardoning with Schindler over wine. The attempt backfires, and he views it as a means of his own power. He has the ability to pardon others, therefore he is superior. He quickly reverts back into being the guiltless murderer that he is.

Ben Kingsley as Stern provides a similar role that Davidtz has, as a witness doing what he can to secure his safety. He puts himself on the line by accepting Jewish employees as factory workers to save them, but he is willing to sacrifice himself to save many others. He is in a permanent place of fear, as his actions are restricted, yet he always manages to get his point across because he knows it is important. His scares turn into gratitude as Schindler himself sees the light. With Liam Neeson at his very best, we understand every aspect of Schindler: why he was such a likeable guy, how he was extremely problematic, what small baby steps it took for him to change his ways, and how different of a man he is at the end of the film.

Schindler and Göth seeing eye-to-eye initially. These two will diverge eventually.

With everyone performing well, and all filmmakers bringing their very best capabilities, Schindler’s List, while disturbing, is tenderly made. It’s surprising how honest it feels, when Spielberg’s warmth is known to hinder a project. It’s as if Spielberg put his signature ways aside to make a film at its barest of basics. He wanted to make a great film, but one that wasn’t sincerely his own. This moment in time is much bigger than a director’s credit. I feel as though all of the cast and crew that took part had this exact same mentality. There’s no need to steal scenes, or turn this into a vehicle for one’s self. There was a noble cause here. A story had to be told.

With all of the grim fine print, Schindler’s List mentions all that has to be told. It remains a moment of contemporary cinema, where a director set in his ways stepped outside of the comfort zone of all of Hollywood, in order to do what was right. It’s a rare case of a Spielberg film actually feeling like pure art. It continues to sit as an untouchable classic, and even one of the finest Best Picture winners ever. Not many mainstream films are this vulnerable or candid for a larger message. For all of the films people love to poke fun about (myself included), I can never fault Spielberg for bringing Schindler’s List to the masses. It is an unforgettable, affecting triumph.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.