Uncut Gems

The secret’s about to be out. I have a major guilty pleasure for early 2000’s house and techno. My justification is that the repetitive synths and beats put you in an emotional standstill. The night life slows down. The pulse of the track replaces your heartbeat. You know exactly what is coming, but you don’t care. I feel that there is an imbedded layer of sadness or discomfort found in these tracks that is often overlooked; perhaps the image of a night gone wrong clashing with these always-bumping tunes. I’m a weirdo, though. I marry sounds to images that aren’t supposed to go together all the time. If I walk past a happy advertisement and hear a kid crying at the mall, that image suddenly conveys a whole new sensation: a state of sympathetic confusion.

The Safdie brothers know exactly what I am talking about. When Uncut Gems finishes, and you are left with nothing but a techno classic over the credits (a remix of “L’amour Toujours” by Gigi D’Agostino), you are seeing a celebration being burned at the stake. Once you gather your breath, and you are being pummelled by nearly twenty-year-old staccato notes (my, how time flies), you will feel like you are experiencing synthetic zen. This is neither heaven or hell. This is the eternity found within the smallest cracks in the Earth: the eternal nothingness. We experience it existentially, but Uncut Gems fixates on this threshold, turning it into a rush.

Howard Ratner’s gambling fixes pace all of Uncut Gems. You’re guaranteed to feel sick.

Forget about how the film ends. The way it starts is also poignant. We see a spectacle at an Ethiopian Jewish mine in 2010, where a worker’s leg has been shattered during his find. Black opals have been discovered here, and this miner’s sacrifice means a rejuvenation of the world over. We cut to the “present”: 2012 New York. Howard Ratner is a jeweller that cannot cure his gambling addiction, either because he cannot stop, or he cannot recuperate the debts that he owes. His marriage is in shambles, and he continues his affair with an employee after he sees his family every day. There’s no question that Ratner is a screw up, and we know this right away. Like that core of an electronic synth chord, Ratner clings onto something exciting to escape his impending doom. There’s simply no way he can get out of this mess.

The plot involves a number of financial investments that Ratner is swerving his way through. NBA legend Kevin Garnett becomes attached to the uncut opal, and trades his 2008 championship ring (with the Boston Celtics) as collateral, in order to hold on to the zen the rock brings him. Ratner uses this opportunity to pull off unthinkable moves. This is clearly a man that only sees the good outcomes from betting, perhaps because focusing on the negative would remind him that he is going to live the worst life very shortly if he is wrong. There was a point where I felt beyond overwhelmed by Ratner’s decision making, and I realized that we haven’t even reached the moments where things actually go wrong. This uneasiness is simply because of how Ratner is as a businessman. It can’t get any worse than this.

Ratner conducts a deal with Kevin Garnett, in order to score big.

It absolutely gets worse. I say with absolute confidence that Uncut Gems is one of the most anxiety inducing films of the new millennium. The Safdie brothers already had me sick with their previous film Good Time (another cinematic downward spiral), but Uncut Gems takes the cake. On that note, it’s fascinating to see the parrallels between these two works. Good Time focuses on one major night surrounding the bad decisions made by a lower class robber, as efforts to help save his brother (of whom he endangered in the first place). Uncut Gems goes toe-to-toe with the big leagues: mobsters, casinos, the rich districts of New York, New York. While Good Time feels unstoppable, Uncut Gems is a runaway train, with endless possibilities that never seem to let up. The Safdie brothers are possible sadists, that love seeing just how far a cinematic adrenaline can go.

Techno is one way that Uncut Gems mimics the fleeting sensation of being caught in an indescribable whirlwind, and once again the Safdies have worked with Daniel Lopatin (of Oneohtrix Point Never fame). While Lopatin’s score is hardly upbeat, his expertise behind both feel-good IDM and ambient soundscapes renders Uncut Gems an ebb and flow of highs and withdrawals. These songs don’t ease off for a second. Ignoring this audible state of depression and elation, Uncut Gems loves championing the anticipation for success. This means waiting for a basketball team to do well because of a hefty bet, hoping a fight will resolve, wanting straggling thugs to leave, or even watching to see your child perform on stage. These idle moments where certainty is up in the air is what Uncut Gems is all about. You never know where you stand, and you’ll be at the edge of your seat the entire time.

Ratner’s personal problems only make Uncut Gems even more catastrophic. It also increases the amount of innocent bystanders that may be affected by his actions.

The biggest recipe to creating uncertainty is the brilliant way almost every single performer has been cast against type. Idina Menzel plays a bitter divorcee-to-be, without a lick of joy found anywhere. Judd Hirsch is almost unrecognizable as Ratner’s blunt father-in-law. Kevin Garnett plays a very serious version of himself; for an athlete’s acting debut, this is one of the finest you will ever see. Even The Weeknd performs as himself, and it isn’t the most flattering depiction either. Outside of Lakeith Stanfield being able to pull off anything sent his way (as always), most of the big names here are people stepping outside of their element, and thus causing a subconscious confusion in us.

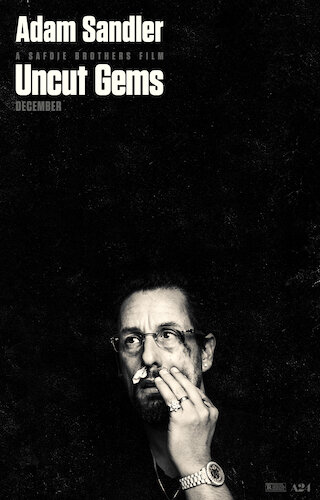

Then, we have the man of the hour. Adam Sandler has never been better. Ever. I have publicly shredded the bulk of his filmography for years (I don’t even care for his ‘90s work. Come at me). This is not the same person that was in Jack and Jill, Grown Ups (and 2), or any of those films. In fact, this is hardly the same actor that even surprised me in Punch-Drunk Love or The Meyerowitz Stories. This is a performer that the world has never seen until now: a comedian that already knew how to dig deep for awkwardness, now channeling that same energy to create vexation. With all of his lies, outbursts, meltdowns, and moments of saving face, you never ever know what’s actually real with Sandler’s Ratner, and it’s a work of beauty. You will have so much fun by not having fun, here. It’s a paradoxical trip.

Ratner’s risks put him in harm’s way throughout Uncut Gems.

Like the Ethiopian Jewish miner with the broken leg, Uncut Gems tries to put a face on the offerings made by the tarnished in hopes of the greater good. It puts bullets in a chamber, spins, cocks the pistol back, and begins waving the gun around, daring you to guess who it will land on. Someone has to put an end to this madness, because this greed fest takes someone else out. Everyone is at risk in Uncut Gems, and it’s because of Ratner’s scrambling to fix his own woes. He involves everyone, creating a tangled nest of broken promises and high waged bets.

From that very first image, of a dismantled limb at the hands of a miraculous find, Uncut Gems is all about the empty space between life and death. The credits sequence wraps this experience up with an Italo disco remix about permanent love. Maybe Uncut Gems is the observation of turmoil through the eyes of the ethereal, with the neon lights and electronic cacophony surrounding every troublesome image. Uncut Gems is an exercise in humiliation, unfamiliarity, nausea, danger, disappointment, and dishonesty, all in the name of experiencing the last shreds of life that only specific events remind us exist. For some people, it’s a high stakes playoff game. For others, it’s the dance floor staple you must hear at the club in the middle of the night. Regarding the Safdie brothers, joy comes from the lights coming up in a movie theatre, when you realize two things. First: your life isn’t quite as bad as you thought it was. Second: there’s a pair of filmmakers that have cracked the code when it comes to making the purest cinematic adrenaline-based dread, and they’ve struck big time again.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.