Amadeus

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. Amadeus is the fifty seventh Best Picture winner at the 1984 Academy Awards.

There are a handful of films that I honestly think have an absolutely universal appeal. I’m excluding cult favourites (The Rocky Horror Picture Show), works integrated into society’s tastes (Fight Club), or anything similar. I’m talking about the very specific films that manage to unite all walks of life: casual movie buffs, concrete cinephiles, film purists, and occasional watchers of all ages and backgrounds. I believe Amadeus is a monumental feature that almost nobody can flat out hate, because of its ability to have something for every single type of viewer. You’re not guaranteed to love it, but it at least channels many different tastes. Unlike Miloš Forman’s previous Best Picture winner (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest), which had elements of being an all around crowd pleaser, Amadeus is a little more daring with some of its taboo moments and executive decisions. It’s not just accessible. It’s bold, too.

I don’t need to inform everyone that Amadeus is hardly a biopic of the final days of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s life. I think that’s a given at this point (especially considering how many people know and love Amadeus by now). Did Mozart and Antonio Salieri know each other? Yes. Did they hate one another? Not quite. Salieri, reportedly, didn’t have a vendetta against Mozart for his success. However, isn’t the story much more interesting as this psychological murder tale? We’re mature and intelligent enough to not read Amadeus as a platform of facts. This take on artistic and integral sabotage is far juicier, because we get a narrative about the obsessions with ruining another (rather than improving one’s self), instead of a by-the-numbers encyclopedia entry.

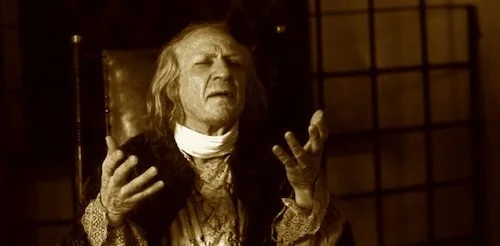

Amadeus comes from the perspective of an elderly, committed Antonio Salieri.

Besides, can’t we view the film as, perhaps, a fictional take from the Salieri presented here? Maybe this isn’t how Mozart actually died, but these are the fallacies conjured by a mind gone awry, meant to soothe an artist that never reached full potential due to being overridden by jealousy. Years of isolation probably made Salieri (well, this Salieri) fabricate his entire life. Even if these events are meant to be true in the film, we still get an artistic turn on the damnations of the creative processes of masterminds, which so happens to use real people. We can insist that writer Peter Shaffer was trying to one-up a prodigy like Mozart by trying to turn his life into more of a symphony, therefore transforming a composer into one of his own pieces. No matter how you look at these decisions, there is a winning point.

So, we listen to Salieri in an asylum (after trying to take his own life) reveal that he is the murderer of Mozart many years before. He confides in a priest as a means of reconnecting with God: the same higher power he swore against during his youth, when he struggled to beat (or even catch up to) Mozart. He burns his wooden crucifix at one point in the film, which is an obvious metaphor for his turn to villainy. However, there’s an even deeper symbol that you hopefully haven’t missed here. As a devout Christian, Salieri is turning against God, by showing a lack of faith in a being represented in the Bible as that of the utmost sacrifice. Salieri is not willing to sacrifice anything himself. He hopes to just be able to be more cherished than Mozart overnight. He misses the points of extreme dedication to a craft, and his own faith. As the older Salieri, he is able to see the worth in asking for forgiveness: a sign of humility his younger self would dismiss outright.

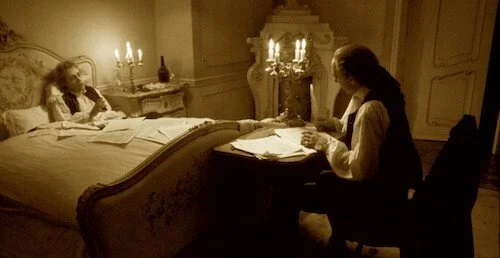

A younger Salieri, constantly in the shadows of Mozart.

Salieri willingly accepts the face of death, if it means stopping Mozart in any way. He takes on this persona literarily, in the third act; a piece of the film that pushes Amadeus from being a great film, into being an astonishing work of art. Mozart’s acceptance of his “visions” is his resignation against his own demons. Salieri neglects to see that Mozart deals with many pressures and problems of his own; his natural talents are only a small piece of his whole. Amadeus also portrays Mozart as an immature goof, as a means of rubbing some extra salt in Salieri’s wounds (and each maniacal laugh of Mozart’s makes me laugh, just knowing how peeved Salieri likely is at every instance).

When Mozart futzes around for hours before a big event, we are just waiting to see how he is able to resolve himself just in time. When he puts his game face on and conducts the hell out of every symphony or movement, that’s it. We begin to see why Salieri is possessed by envy. This guy seemingly breathes out genius at any given second, and yet he’s a jackass child that puts very little effort otherwise. That simply should disqualify him from any of the praise he gets. These are Salieri’s thoughts, and it drives him into insanity. So, he goes the evil route and vows to turn Mozart insane, too. He will seemingly scrunch out any remaining bits of natural gifts left in his body, mind, and spirit. He feels Mozart stole all of his hope, and so he will do the same to that of whom he once admired.

Mozart is extremely silly; a method of maintaining comedic relief, as well as ammunition for Salieri’s extreme distaste for him.

As a philosophically rich production, Amadeus also benefits from virtually every other cinematic element. The performances are top notch, starting with F. Murray Abraham giving a Best Actor winning turn for the ages, and one of the best to ever win said award. Tom Hulce shouldn’t be forgotten either, as his ability to leap from hilarious to dramatic, then dramatic to tragic, is an unbelievable achievement in its own right. The world building here features many fine cogs in the machine of the cinematic illusion, including fantastic costume designs, breathtaking sets, and jaw dropping hair and makeup work. The film won eight Academy Awards, but it was hardly because of its Best Picture stature. This is a well-made feature through and through.

It all helps to sell this tale of artistic vengeance. We are slowly sucked in to a world society once new in the 1700’s. We are gifted a dramatic take on the mysterious death of Mozart (no one is certain how he died to this day). We end up in mythological territory by the final act, with Mozart allowing death to enter his home and consume his very soul. Salieri crowns himself the finest example of being inept, and gifts his fellow asylum patients with his blessings, acknowledging everyone despite their inability to ever leave the shadows of others in society. For a revisionist piece, Amadeus ventures down some dark — yet rewarding — corridors.

Salieri tending to Mozart, as a means of dissolving his soul and artistry.

Amadeus may have won people over for being a damn fine period piece film back in 1984, but it booms louder than ever before over thirty years later. It is a go-to work for Film 101 classes, and even in some music spaces. It’s not factually accurate, but I think music teachers love the depiction of creative struggle and insecurity depicted here. Plus, it’s an immensely strong drama, through the eyes of an artist slowly, mentally dying (whose body is also deteriorating, and his soul was deceased years ago). Miloš Forman knew how to make a good film, and had done so a number of times. Seeing him push himself (and everyone else around him) to make a gigantic statement like Amadeus is a marvel in and of itself. It’s as audacious as it is familiar; as dark as it is light. It’s watching life battle death, only for the death of one to become life (in the form of a legacy), and the life of another to become death (a permanent struggle with grief and ineptitude).

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.