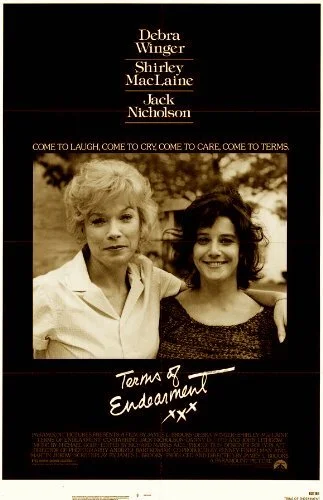

Terms of Endearment

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. Terms of Endearment is the fifty sixth Best Picture winner at the 1983 Academy Awards.

James L. Brooks was comfortable with his television works. He helped warm hearts with The Mary Tyler Moore Show, and was coming around to creating chuckles with Taxi. Eventually, he would help have a hand in the most successful of animated shows with The Simpsons. That's jumping too far ahead, though. He was about to show his affinity for the big screen as well, by 1983 (a decade he seemingly succeeded in, including the fantastic Broadcast News in 1987). Terms of Endearment was his effort of bottling up every single emotion his shows dished out over the span of many seasons; the challenge was achieving this in a very short amount of time.

I flat out don't care what anyone says. Terms of Endearment is a magnificent film. The Ingmar Bergman obsessive in me would have liked the dark horse in Fanny and Alexander to have picked up Best Director, or be nominated for (and even win) Best Picture, but that wasn't going to happen, and we all know it. Plus, unlike Ordinary People's connection with Raging Bull through the Oscars, I feel as though much of Terms of Endearment's negative perception come from people just not interested in a schmaltzy comedy drama from the early '80s. Too bad. I'm judging films by how they stand by themselves, and Terms of Endearment is sensational to me.

Even though many relationships are featured, the primary connection in Terms is between mother Aurora and daughter Emma.

Not many films that coast through the years can make their rushed natures feel authentically like life slipping away. That mission is usually futile. Terms greatly succeeds in its attempts, because of what Brooks decides to focus on. These include the very first recollection of baby Emma, as her mother (Aurora) is already devoting her life to being in charge of her child (her obsession with committing to this mission becomes overbearing, and was already intense from this initial memory). We zip through Emma’s adulthood, and Aurora’s attempts to settle down and live a life of individuality. Both women go through their own rough experiences, as they relate more to each other than they may wish to admit (since they usually don’t see eye-to-eye when they confront one another).

We tend to forget just how quickly Terms marches along, so reaching major turning points hits us like a variety of surprises (whether they be good or bad). If anything, we are only watching the literal terms of endearment that every single character dishes out to each other. These can include flat-out compliments, tough-love commentary, or even words of anger, only said because someone was hurt (that’s one indication of love if I ever saw it). Every scene contains at least one line that is said from the heart, whether the feeling is of pure adoration, damage, anguish, disappointment, or regret. Not every attempt at conveying love is the right choice, and many of these instances can be considered toxic to a degree. Yet, these are all attempts, and they’re all signs of these imperfect characters being mightily human.

Moving forward can be as difficult as staying put, but life is never easy. Terms represents that hard truth well.

Through tons of laughs, and many tears, Terms of Endearment is a major success by James L. Brooks to elicit the kinds of responses his previous shows have been capable of conjuring over the spans of years (only, here, this is accomplished in a much shorter time frame). What makes Terms an even bigger must-see for Brooks fans, is how well a cinematic angle matches his story. A scene that always stands out for me is the moment where Aurora and her date Garrett are driving on the beach; it oddly feels surreal and off-kilter enough to seem ripped from a Federico Fellini film (maybe it’s the waves, the dressed-up couple on their date, and the rich colours and floaty camera panning). Brooks has been able to pin point the types of conversations that humans have with one another, but this aesthetic encouragement through his transition to the big screen creates a sublime marriage between quirkiness and beauty. Terms of Endearment may lean on its conventions, but it’s a finer example of how these blueprints could be worked in the ‘80s.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.