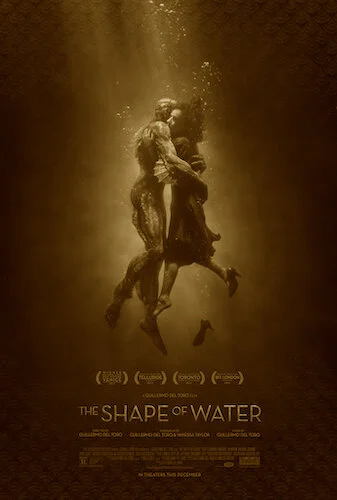

The Shape of Water

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. The Shape of Water is the ninetieth Best Picture winner at the 2017 Academy Awards.

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King was previously the oddball Best Picture winner. Fantasy just never did well at the Academy Awards, outside of that film (and the entire The Lord of the Rings franchise). You’d find some nominations for hair and make up, and maybe for special effects, but fantasy just isn’t meant to take over awards seasons. The closest you’ll get are science fiction works (and even those never actually take charge of the Best Picture race). In the mid 2000’s, Guillermo del Toro created the perfect adult fairy tale in Pan’s Labyrinth: a gruesome, whimsical look at the years of the Francoist dictatorship, when the citizens of Spain were recoiling from a civil war (that neglectful guardians brought their children to, assuming this was the next Harry Potter).

It was about time del Toro returned to this same drawing board, and he did so with The Shape of Water: the only fantasy stand alone film to win Best Picture.Instead of the Spanish Civil War, we are now looking at the Cold War in ‘60s America, during a time of heightened, blatant intolerance (conveniently covered as a means of preserving the nuclear family image). We follow the cleaners of a government base that houses weapons and experiments. We mostly focus on Elisa, who is a mute that is often overlooked by society, aside from her closest friends (who are also cast aside from society, either because of their skin colour, or their sexual orientation). In comes a biological “asset” for the base to utilize as a means of getting an advantage over Russia: an aquatic creature that greatly resembles a human structurally. And thus, the fairy tale begins.

The Shape of Water is shot like a mature children’s film or storybook, to create the illusion that this is a fable for adults. It greatly succeeds in making adults feel wide eyed like kids.

Like marrying a B-movie horror and a German expressionist romance, The Shape of Water looks far back to advance forwards. Here, the “monster” is meant to be loved. The sharp angles and close ups are inviting. Everything is jarring, only because society has told you it was meant to be jarring. In an insensitive era, we almost feel as though we are gawked at in the same way the lead protagonists are. The “all American” Colonel Strickland is the biggest villain in the film, and yet he encompasses most of the basic traits of a cinematic hero during the time period Shape takes place (outside of all of his awful actions, of course). It’s as if del Toro is exposing these archetypes that were championed for decades, and revealing the natures of the misattributed “side characters”. The shape of water is formed by whatever contains the liquid. Storytelling can shape characters in any way. These blueprints that Hollywood abided by years ago (and still do to a degree) aren’t necessary what’s best for the medium.

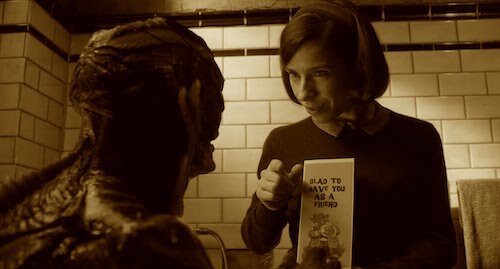

As the film gets going, and the tensions between characters rise (as well as the romance that many people still can’t somehow get by; if there was ever a time to use the “it’s only a movie” excuse, now would be the time), Shape becomes a series of catalysts leading towards a chemical reaction of many sorts. The beauty of Shape is shown in spades during Elisa’s tender moments with the “asset”, like a princess meeting her partner and creating a new world around them. This includes the musical number, where Elisa finally has a literal voice she can provide to exclaim her newly found love through the “asset”. It’s an obscure romance, but it’s a powerful metaphor of ostracized cinematic conventions being broken, and a juxtaposition of progressive societal perspectives with cookie cutter filmmaking that needed to be expanded from eons ago. The two ideas really work well together.

Elisa bonding with the “asset”.

The Shape of Water captures the adult rendition of a child’s storybook quite well, just in the same way that Pan’s Labyrinth did. It even has that bittersweet ending, which adult eyes know is a tragic conclusion, but the youthful side of us believes the saving of magic (no actual child should be watching films like The Shape of Water, mind you). Gory and explicit reality intersects the fantastical moments, tossing us between what we know now as mature members of society, and what we believed as a generation being introduced to the world in full. Guillermo del Toro is just so good at making mature fantasies actually purposeful (and not just adding “dark” or “sexy” elements to children’s’ cautionary tales). There aren’t many filmmakers as innocently imaginative as he is. In a heated new era, his curious analysis of modern day politics is exactly what we needed for it to be more digestible (and even make a bit more sense), even if it includes a cleaner falling in love with the amphibian god she is trying to save.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.