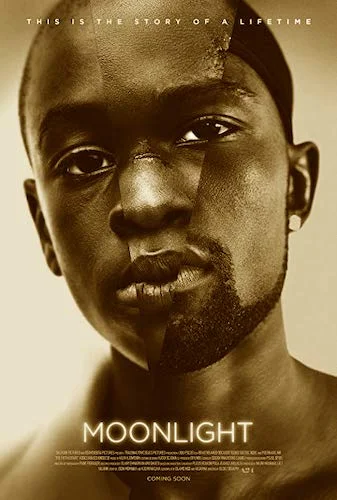

Moonlight

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. Moonlight is the eighty ninth Best Picture winner at the 2016 Academy Awards.

From Spotlight to Moonlight. The Academy Awards jumped between two similarly titled films. When you really try to grasp at straws, there are some similarities between these two works (even in a contrastive type of way). Spotlight was all mind, with evidence laid out through and through, to try and shed light on a societal issue we already knew. Moonlight was all heart and soul, that presented all of the hurt of the lead character Chiron, by providing a podium for the unheard stories that really weren’t being represented in cinema. Moonlight was the first film to star predominantly African American performers, and present a story focused on the LGBTQ community to win Best Picture. It’s one of the very few considerably arthouse films to win, and it remains truly unlike any of the previous winners. Even Midnight Cowboy was experimental (considerably), and The Last Emperor was grandiose. Moonlight was inspired by the works of Wong Kar-wai, and it is colourful, poetic, humanistic, and tender.

To this day, Moonlight’s win doesn’t feel real. It’s like if Hiroshima mon amour, My Beautiful Laundrette, or Days of Being Wild winning Best Picture. It also doesn’t help that the now-infamous incorrect reveal of La La Land as the winner over Moonlight has tampered its legacy. It doesn’t take anything away from Moonlight, but the actual win is attached to controversy, rather than pure triumph. Director Barry Jenkins rightfully proclaimed “To hell with dreams” during the fiasco, likely because he was conflicted. On one hand, he pulled off a miraculous Best Picture win; Moonlight was exceptionally low budgeted (around four million) arthouse fringe film about marginalized people. On the other, the win was done in such a clunk fashion. Is this really the way a groundbreaking film like Moonlight should pave a path ahead? Well, any which way, I suppose.

Moonlight is divided into three chapters of Chiron’s life.

Jenkins was relatively new to the filmmaking game when Moonlight took the world by storm. He released Medicine for Melancholy eight years earlier in 2008, which was a truly independent feature made for fifteen thousand. He had been meaning to adapt a work by the revolutionary novelist James Baldwin, but that project kept being stopped-and-started (eventually, If Beale Street Could Talk was released in 2018). He had meant to speak about his own experiences through Baldwin’s work, but found a personal avenue in the mean time. Impelled by the unreleased student play In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue (by Tarell Alvin McCraney, who received a story credit for Moonlight, along with the shared Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar), Jenkins found himself in a way he wanted to present to the world.

In the same way that Jenkins vowed to express his struggles, he wished to toss in all of his favourite influences. Again, Kar-wai was brought up earlier (much of Moonlight feels spiritually connected to In the Mood for Love and Happy Together), but you can also find other sources here. Moonlight begins with the exact same Boris Gardiner track that kicks off Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly: a hip hop album that changed the rap landscape just one year prior. The use of popular tracks to describe a scene has been done many times before; one key example in Moonlight is the touching use of “Hello Stranger” by Barbara Lewis as a means of asking for forgiveness from one former partner to another. Jenkins enjoys representing what has galvanized him into becoming a filmmaker, but he clearly knows enough of the craft to take matter into his own hands, and conjure his own voice. As a second feature, Moonlight couldn’t get any better. It’s astoundingly masterful.

Chiron’s relationship with his mother is very strained; a frequent theme in Moonlight.

Moonlight gets split into three different chapters when it comes to the life of lead character Chiron. You firstly get a snippet of his childhood (titled “Little”: his nickname). Part two is “Chiron”: his teenage days where he discovers who he truly is, while trying to get through high school woes and a mother that is spiralling out of control. The third section is “Black”, when adult Chiron has stripped himself of all of his personal traits from his youth. In “Little”, Chiron is taken in by Juan; a drug dealer that recognizes the same goodness that he stifles from the world, in Chiron. By the time “Black” rolls around, we see Chiron has been forced down the exact same path as his guardian figure. He was cursed by a societal-imposed fate, despite his best efforts to break out of this constrictive mold.

The way Moonlight is divided encourages many mirrored themes, moments, and characters. Juan’s final hours, and Chiron’s stunted growth as a person, are the tip of the iceberg. Chiron’s mother Paula is shown in a more understanding light, since you only see her moments of heavy addiction, and her attempts to rectify her wasted years as a loving parent for her son. Then we have Kevin, Chiron’s friend and potential romantic partner. The way the film skips long periods of time, we can only imagine the personal guilt Kevin harboured for many years (especially concerning someone he loved). We view life teachings, certain moments, and whatever Jenkins felt was necessary for us to latch onto in Chiron’s life.

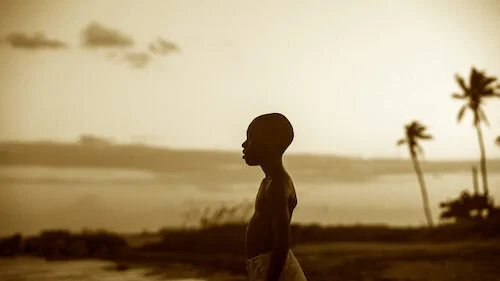

Juan bringing Chiron to the beach, almost as if he has baptized him into a new, purer life.

We don’t get all of Chiron’s life, but we get the big picture. We understand how a troublesome childhood can lead to a shyer teen not knowing how to fend off his bullies. We then see why a rough experience with one’s self discovery or disapproved sexuality can cause that person to shelter themselves romantically for as long as possible. Chiron is presented as just one person’s story, amidst a whole community of promising faces of a new generation being crushed by classist divide. Moonlight doesn’t need to discuss how these characters (especially the adults in the first chapter) wound up in their positions; it’s implied that the Liberty City neighbourhood is strangle-held by many years of oppression. Juan’s quote that he held close to his heart since childhood (“In moonlight, black boys look blue”) is a means of understanding that marginalized people can see the same struggles in their fellow person, and that it envelops them all if a community has been neglected by richer societies.

Right away, we know Chiron is having it hard. He finally can confide in someone with Juan (and his girlfriend Teresa, who also acts as a secondary mother for Chiron). That’s when he opens up about his sexual curiosity: he asks Juan, essentially, if it is okay to be gay (and, if so, why do the other boys say derogatory things to him). It’s a slight hint at what is next for Chiron, after seeing some brief instances where Chiron may have made his revelation. We see Chiron at his most sexually liberated in the middle chapter, and even then it’s only a single moment with his best friend. “Black” has Chiron barricading himself again, perhaps even more so than he did as a curious child. The final line of the film (the greatest piece of dialogue of the 2010’s, in my opinion” has Chiron trusting his deepest inner thoughts for one last time: by telling Kevin he was the only one, and he touched no one ever since. In a life where his proper guardians died or were chased away, his birth mother untended to him, and his best friend was forced to beat him, Chiron ached for love of any sort.

A teenage Chiron, recuperating after a beating.

Jenkins so cleverly knows exactly what moments of Chiron’s life to include. We learn a little bit about each stage of his life, and the rest of each chapter plays out for us. So much is told by visual story telling. The opening shot (a 360º pan of Juan checking in with his drug hustlers on the street) tells us all that we need to know. This is the suburb of Miami that we are going to stay in. This is an important character, and this is his job. Here is how this character treats his employees. When Chiron comes crashing through the story, we are Juan: different people than Chiron, stumbling upon this child that’s in danger. We also want to get to know him, and understand how he himself got here. Moonlight provides a tale for many people that have been barely represented in film before now, but it’s still very much Chiron’s life laid out for us. So, like Juan, we aim to investigate, to try and help. Any child that is being abused in any way means a life that can forever be tainted. If it can be prevented, then it must be at all costs.

Moonlight can only do so much to help Chiron (especially since cinema is mostly an observant medium). What it can do is understand him the most. Through the rich cool colours (one thing that separates Jenkins from similar filmmakers, who favour more radiant or juicier colours), we see a Miami that has been toned down by internal depression. Jenkins and cinematographer James Laxton focused the photography to enhance black skin (rather than many works that are catered for white skin), allowing Moonlight to celebrate the communities and cultures it aims to feature. Although much of Moonlight is sad, a portion of its aesthetic story is catered to promoting African Americans in cinema. These positive moments are given the complete care necessary by Jenkins, turning into Moonlight’s much-needed glimpses of personal adoration.

An adult Chiron reconnecting with Kevin, after years of separation.

Not many films are as special as Moonlight. It was unquestionably a decade-defining film as soon as it premiered in any theatre. It dominated the film festival circuit, and it’s as clear as day as to how. It garnered the praise of many filmmakers, including Jonathan Demme, who personally attended a screening and vowed to talk to Barry Jenkins, just to let him know how blown away he was. Every single piece of acclaim Moonlight continues to attract is warranted. It utilizes cinematic nostalgia to draw you in, cultural appreciation to enlighten you, and hard-hitting realities of marginalized communities. Jenkins’ knowledge of cinema led to Moonlight and its poetic core, aesthetically stimulating exterior, and socially expressive middle. Moonlight was awarded Best Picture, and then subsequently named one of the best films of the 2010’s (if not the best film) by many publications. In a number of years (maybe even sooner), Moonlight will rightfully be declared one of cinema’s finest hours throughout history. It’s crazy that we all got to experience this in theatres (or upon release, anyway). Arthouse met literary writing and political undertones, in a way that was still appealing to the mainstream. Moonlight seems impossible, and yet I’m certainly glad that we have been blessed by it.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.