12 Years a Slave

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. 12 Years a Slave is the eighty sixth Best Picture winner at the 2013 Academy Awards.

There shouldn’t be any competitions when it comes to making historical pictures of troubling, catastrophic matters. However, we do believe in precedents being set, by filmmakers that know how to convey a particular subject as powerfully as possible. Back in 1993, Steven Spielberg put all of his typical tropes aside to humbly make Schindler’s List, which has become a staple in artistic depictions of the Holocaust. As an interpretation, Schindler’s List is up there with actual documented footage (like the ambitious Shoah, or the personal The Diary of a Young Girl) as being one of the most affective takes on that particular dark time in civilization. Twenty years later, Steve McQueen — a filmmaker with much fewer works under his belt at this point — created a similar statement with his take on the slavery of African Americans in the 1800’s. 12 Years a Slave is a rare film where you know of its classic stature immediately. Even halfway through the film, I felt exactly what I experienced during Schindler’s List. 12 Years a Slave is a film of that caliber with this particular topic.

The most notable way that this is so, is how 12 Years a Slave sheds light on the many signs of slavery that you may not have even considered (the ugliest parts). Schindler’s List never stopped showing the many calculated ways that Nazis targeted many communities (in this film, the Jewish community is focused on the most), and 12 Years a Slave is no different in its mission to reveal how African Americans were tortured. These specific accounts come from Solomon Northup: the author of the memoir the film is based on. A free man living in New York with his wife and children, Northup was conned into being drugged by two men seeking his skills as a violinist for employment. Since these are all accounts by Northup, 12 Years a Slave is a highly accurate depiction of the brutal extents of abuse African Americans endured; aside from a couple of fabricated moments by screenwriter John Ridley, the film has been praised by historians for its factuality.

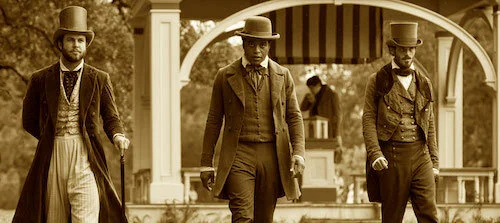

Solomon Northup when he was free, unknowingly being trapped by conmen wanting to sell him into slavery.

From that point, 12 Years a Slave breaks away from Schindler’s List, outside of both works being the strongest retellings of these specific historical monstrosities. 12 Years a Slave is not shy, and it boasts its arthouse influences on its sleeves with great pride. These include extreme close ups that almost feel Lubezkian in nature; credit goes to Sean Bobbitt for his stunning work here. There are also long, minimalist passages, the use of single takes or blurred images to mess with your focal points, and deep mise-en-scéne to detail all of the happenings of a scene at once. As ugly as the content in 12 Years a Slave is, these images of horror are shot in a breathtaking way, as if this confusing contrast is meant to mess with your mind. It’s like noticing life in the nature around the characters, and then realizing the brutality in the foreground. It’s the destruction of life, especially the innocent lives that have been tormented out of bigotry and embedded, disgusting racism.

Everyone goes on about Hans Zimmer, but not enough people continue to bring up his work in this film. His score is more delicate than usual, but it matches the images on screen much better (rather than being bombastic, or enticing). There are moments where Zimmer’s score picks up, but only to keep up with the visual moods on screen. The creation of Northup’s memories through costume and set designs is also worth noting. There is no hiding the fact that all of this happened. There aren’t any artistic interpretations that mask truth. All you see is a depiction of reality. The detailing of each and every visual aspect makes it so. It’s incredibly difficult to take in, because you are presented with everything as is.

Scenes of violence are presented as rawly as possible.

Northup’s story experiences many different turns, but we know relatively how it will end up. The title gives away at least one part of what we know: Northup’s tale here will last twelve years of his life. Knowing that this is based on a memoir reveals another possible outcome: that he survives this turmoil (or, his documentation of these years were discovered, and he may not have escaped slavery). Either way, we know enough about Northup before we even begin the film. So, his tale is as much his own as it is the voice of those that were in slavery with him. We are shown the many different levels of slavery through his writings, including someone like Patsey, who is objectified by her master Edwin Epps, and sexually abused (since Epps lusts for her, but is a big enough racist to not respect her). A similar storyline can be found in the brief appearance of Harriet Shaw: a former slave that a master married, and is now “free” as a housewife; Shaw hopes for a brighter future for Patsey, seeing as she can identify much of what Patsey is going through.

Nonetheless, for all of these stories to carry the weight they deserve, screenwriting can only do so much. Performances have to go the rest of the way. As Northup, Chiwetel Ejiofor is a perfect anchor for the film. He delivers as much oomph as needed, but allows his silent emotions to do a lot of the carrying for each scene. He also allows other performers to shine, thus gifting many muted voices with a legacy. This includes Patsey, played in a breakout role by Lupita Nyong’o, who frankly runs away with the entire film, despite her small part. For every sign of restraint Northup hangs on to, Patsey opens up enough to relay all of the pain and anguish of someone that has lived a life as hard as she has. We see enough horror through Northup’s gaze. Taking on Patsey’s daily occurrences is too much. That’s when you really notice the utmost hideousness of how slave owners treated people for the most pathetic of “reasons”.

Patsey is a window to the even-worse aspects of slavery, thus adding another layer to Northup’s writings.

The rest of the cast, good or evil, is rounded out by powerful performers. Michael Fassbender, Paul Dano, Sarah Paulson, and Paul Giamatti are the many atrocious sides of plantation owners, and slave sellers. Alfre Woodard, Adepero Oduye, Michael K. Williams, and others, are the numerous other voices of slaves found in Northup’s revelations. Then, we have middle ground characters that add an extra layer of nuance here. William Ford (Benedict Cumberbatch) is a slave owner. There’s no dancing around this. What is interesting to see is how much more he actually cares about people like Northup, as if he cannot save Northup for his own safety, but he wishes he didn’t own people either. He still buys slaves, but he tries to actually treat them like the people that they are. Then, we have Samuel Bass (Brad Pitt): a carpenter from Canada, who works with slave owners, but is willing to do whatever it takes to help people like Northup, regardless of who “owns” them. 12 Years a Slave becomes so much more complicated, with characters that are actually detailed humans. The morality isn’t stuck with “good” and “bad”. There are so many varying degrees of goodness and evil, as there are in life.

McQueen takes all of these superstar elements and sews them together, with some of his own brilliant decisions (he absolutely should have won Best Director, and it’s a sham that he didn’t). The single shot take of the “soap” scene makes you feel like a witness to a sight of devastation, and it’s impossible to look away at such a cruel act that is right in front of you and won’t be hidden. The uses of foregrounds and backgrounds is always being taken advantage of. This includes privileged slave owners dancing in front, only for the camera to zoom in to the slave musicians in the back and show how their love has been turned into a punishment; they are never acknowledged by any of the dancers, but only by us viewers. The idea of Northup’s name is heavily included throughout the film, rendering the final moments as one of the bittersweet scenes of the 2010’s; Northup missed everything, but he was never forgotten by his loved ones.

Edwin Epps looking at his slaves as they get to work, without an ounce of sympathy.

McQueen has too many fantastic decisions to write about, but there is one final moment that will forever stick with me. When Northup is finally freed, and the camera is zoomed in right on his expression, his surroundings blur. Patsey collapses, and we don’t see the aftermath. Northup feels a plethora of emotions: joyful, depressed, scared, unsure, overwhelmed. McQueen doesn’t try to put a stamp on this moment, because there is no sure answer as to how someone in this situation would feel. At the same time, McQueen acknowledges that this ends what we know of the other slaves Northup knew. This is a victory for Northup, but an uncertainty for everyone else. We don’t end hopefully either, given what we know about slaves like Patsey and their predicaments.

On that note, Solomon Northup also has a bit of a sad end. He became pivotal in slave abolishment once he returned home (this includes the writing of his novel). The film ends with an anecdote: Northup’s death and burial isn’t known about. We have no idea what happened to Northup after his efforts. We will drive ourselves insane if we try to figure it out, knowing that there is a possibility that the worst could have happened to him. Or, we can try and hope that he lived the rest of his life quietly and peacefully, and documented history simply hasn’t pried into the latter years of his life. The moments we do know have been masterfully represented in 12 Years a Slave: an instant classic. In my previous writings for this project, I’ve touched upon films like Casablanca, The Godfather, and other opuses. 12 Years a Slave is one of two major moments of this decade, where I feel like this generation has experienced that same phenomenon from decades ago, and the Academy Awards could sense the same sensation (Moonlight being the other instance). You just know time will be good to 12 Years a Slave, just like the film aimed to be good to the words of Solomon Northup, and the identities of the millions that had their lives stripped away by slavery.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.