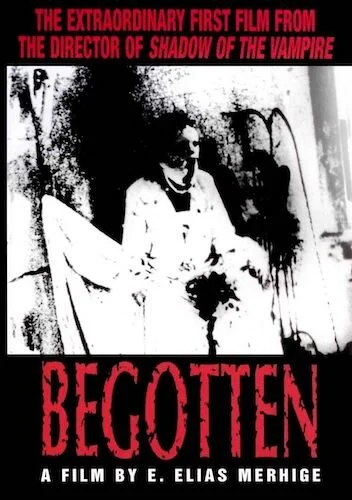

Begotten: 31 Days of Horror

E. Elias Merhige’s name has all but disappeared off the map of cinematic cultural awareness. Sure, he made the insanely underrated Shadow of the Vampire (a love letter to horror filmmaking in such a campy, self aware way), and he was attached to Marilyn Manson for a little while, but he hasn’t really done much in the last fifteen years. All that’s left and widely discussed — to some degree — is his debut Begotten: a savagely disturbing art horror that can be interpreted in different ways. I personally view the film as a testament to humanity’s hubris, resulting in the death of faith and nature (two foundations of our health in different ways, depending on who you talk to). Either way, all sides lose in Begotten, where Mother Nature and the second coming don’t stand a chance against the human race’s selfishness.

Producing his film to the point of bleached out, fuzzy images is much of the appeal of Begotten, which was created as a pseudo silent film. The film was scratched with sandpaper, re-processed over and over to create over saturation, and battered in other ways to instil a new kind of a silent horror homage. It’s not quite the style of yesteryear, but it is very much its own entity, which definitely adds to its legacy; there really is no film that looks like this one. It makes the graphic imagery even more difficult to understand, and it’s a rare instance where our imaginations are competing with what we’re actually seeing, scaring us even more than just the imagery itself. Then, there’s the sound, where no dialogue or music is used; only repetitive, unsettling sounds set to the images are used, so the end result is neither hypnotic or captivating. If anything, the sound is abrasive, making all of Begotten (purposefully) painful. The sounds aren’t exactly large in any way, either, so the images usually outweigh what we hear, creating a very uneasy imbalance. It’s awfully daring.

Begotten is produced in such a way that it resembles old silent horror films in a completely different way.

Underneath all of the graininess is Merhige’s oblique storytelling, where a god (or possibly the God) commits suicide, abandoning their own creation in order to birth a daughter and son to carry on for him in the midst of his own demise. We follow both “Mother Earth” and “Son of Earth” and their futile attempts to bring peace to the world. Even though they don’t give up quite like “God” has, they still suffer humanity’s greed and perversions. Begotten is basically watching all of this, as if it were a symbolic snuff film. In the Bible, John 3:16 discusses God delivering his own “begotten Son”, allowing followers to live forever in heaven. I’m not sure if Merhige is a religious man, but he does incorporate religious imagery here (not through having a god, but through a living mortal version of himself via his son). He definitely merges this religious connotation with something more pagan or occult based, including nature as a spiritual embodiment. I don’t believe Merhige was trying to push any beliefs, more than he was making a statement on how all walks of life (and what they hold dear to them) suffer when we fall to civilization’s misdeeds and evils. It doesn’t matter what your faith is. The opening image of a prolonged, sacrificial suicide hits everyone.

With blank faces, the three main characters resemble living statues, almost impressionable by you the viewer in a multitude of ways. So much of the horror that comes from Begotten is the filling in of missing pieces; because the film isn’t explicitly about any belief, it’s difficult for all believers to watch., for instance. Even though the film is beyond graphic and hides absolutely nothing (even behind its overly processed visuals), it still feels empty enough to warrant an explanation, and I’m sure your efforts to figure it out your own way are as nauseating as my own. Truth is, Begotten finds the inexplainable distance audiences (especially of much later times) have with older, choppier horror films; even with lower production values, something just seems creepy about them (the inability to personally identify with them in any way, perhaps). E. Elias Merhige captured this feeling and ran with it in his debut opus, to the point that it hasn’t been done since. It’s not exactly a film I’d recommend you watch with loved ones, but Begotten is just so unique, it demands to be seen by any horror fanatic at least once, if you dare.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.