Cannibal Holocaust: 31 Days of Horror

For all of October, we will review horror films. Submit your requests here, and you may see your picks selected!

Cannibal Holocaust is so graphic, director Ruggero Deodato had to come on live television to prove that people didn’t actually die in his film. Now, that’s the kind of press that gets some buzz going around a sociopolitical horror film, particularly one that indulges in shock. The unfortunate truth is that Cannibal Holocaust is more or less an event for horror junkies. I should know: I was one. Teenage me vowed to see all of the most insane horror films ever made. It resulted in an exploration of the shock genre, which quickly led me to realize just how absolutely useless the genre is. I was watching nonsense like Men Behind the Sun, which, to this day, is the most vile film I have ever seen (and I don’t wish to entertain it by releasing an article or review on it; it doesn’t deserve my time). Fortunately, Cannibal Holocaust is ahead of the pack, which was a really lowly set bar to begin with. The problem is it’s not quite as intellectually or artistically rewarding as, say, Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom: a modernization of the writings of Marquis de Sade.

Of course, Cannibal Holocaust shares more in common with Salò than most of the other dreadful films in the genre, because it genuinely has something to say other than “violence is disturbing” or “atrocity is ghastly”. A film crew conducting an anthropological study in the Amazon is searched for, only for their footage to be unearthed. Shot in such a way that mimics real documentary film, the picture-within-the-picture is where Deodato can flex his filmmaking muscles, and go the extra mile with the gore presented within. The American explorers are insensitive and crass, and they often antagonize the cannibal tribe they are researching. In there remains a statement on civilizations and their tendencies, and it’s a rather interesting spark for a discussion. Unfortunately, the relentless gore usurps any of that. In Salò (I don’t mean to keep referring back to this film, but not many shock films are worth a damn), the disturbing imagery is a part of the statement itself. In Cannibal Holocaust, it’s more of a frame of reference for those back in the theatre (in the film, again) watching the footage, to see the depths of the human condition of both societies. We get the picture, but it doesn’t do much to make us think anything more than “What the hell am I watching?”.

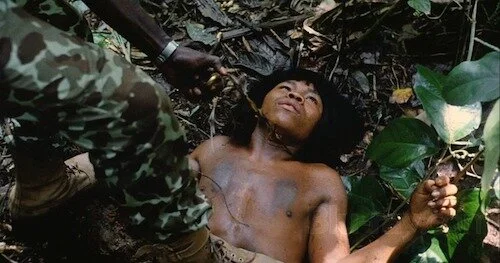

Cannibal Holocaust is deeply invested in its graphic imagery.

The line gets blurred even more when the animal abuse gets mixed in with the simulated human massacring (only the animal murders are very real, and excruciating to watch). Of course, this only strengthens the realism approach, but by now Cannibal Holocaust is deterring you rather than gripping you. A major reason why I can’t stand most shock films is that there is a fine line where shocking too much can ruin the connection a film can have with an audience, and not in a niche post modern way either. Cannibal Holocaust gets awfully close to remaining on the right side, by offering some harsh commentary on the human species, particularly those that dare call themselves civilized. Unfortunately, it crosses that line and never really comes back. There are glimpses of something profound here, even within the unsettling images; the infamous scene where a tribe member has been impaled through the mouth is as captivating as it is challenging.

I don’t think Deodato set out to make the most disturbing film of all time, because Cannibal Holocaust would be even more explicitly lazy in every other department outside of excess and exploitation. I just feel he got carried away, turning Cannibal Holocaust into a pilgrimage for those seeking the most stomach churning films ever made. They may leave thinking they’ve seen something of brilliance, but compared to the majority of the other films in the genre, it is; almost anything slightly better will seem like a masterpiece if that’s all you watch.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.