The Best 100 Films of the 1960's

WRITTEN BY ANDREAS BABIOLAKIS

Going backwards in my decades experiment is occasionally strange, especially when you reach a decade like the 1960’s. Of course, we know that this is where a lot of changes in mainstream cinema — particularly Hollywood — happened, so pitting together these different eras can be a bit of an eye opening experience. Anyway, that’s cinema. Let’s focus on where everything else was for a second: television was becoming more widely accessible, music was reaching a contemporary status with rock and roll and pop, and the world was trying to unite via “peace” (despite the wars that were ongoing and would start). Let’s now return to my initial point: these other artistic mediums were either getting going, or were becoming something of a different nature. Film was old enough to be evolving into its next phase. Strange, right?

Nothing was more strange than these changes, either. An influx of waves (be it French, Japanese, Czech, or New Hollywood) were colliding together to make the biggest statements to the world. The styles of old (westerns, musicals) were trying to rush in their final says before revisionism destroyed them for good. Black and white was finally being replaced by colour — Technicolor, that is — once and for all. Of course, it’s obvious that this is the time when a lot was happening in cinematic history, but really smushing all of these titles together hits that point home. For a medium that was constantly shifting, film may not have had as much movement as it did in this point and time.

In 2020, 1960 is sixty years ago, which is also sixty years after 1900; around the time when film was being used to tell stories in a big enough capacity. In a linear sense, this is around the halfway point to where we are now. Does that justify all of the movement that happened? Whatever does, all I know is that this decade is truly one of a kind for film. I keep saying this, but now I can officially confirm this (since I’ve begun my work already on the ‘50s, ‘40s and other remaining decades): the 1960’s are by far and beyond the most difficult decade to rank, and that likely won’t be changing now. I love the idea of ending this year off with the most challenging list I’ve had to make up until this point, because it feels like my biggest accomplishment in accumulating all of cinema’s finest works. Either way, I did my very best; I could have gone to two hundred, most likely. Here are the best one hundred films of the 1980’s.

Disclaimer: I haven’t included documentaries, or any film that is considerably enough of a documentary (mockumentaries don’t count). I haven’t forgotten about films like Warrendale or Don’t Look Back. I’m keeping them in mind for later (wink wink).

Be sure to check out my other Best 100 lists of every decade here.

100. if....

The school system in Britain was notoriously difficult and abusive, but Lindsay Anderson’s hypothetical dark comedy if…. willingly goes way too far, much to the amusement of bitter audiences. Championing a relentless response to strict education, a film like if…. could not be made today by any means. In fact, the film gets so pessimistic, its climax is hardly rewarding or held accountable. Like a problematic thought, if…. presents itself, and asks, well, “what if?”. What a terrible thing to think, and yet Anderson couldn’t care less. Neither does if….: one of the most savage of satires in all of cinema.

99. Spartacus

In Stanley Kubrick’s classic era (which was, well, everything but his first two efforts), only one film sticks out as a sore thumb: the creative mutt known as Spartacus. This sand-and-sandals epic was a production mixture concocted by director Kubrick, producer Edward Lewis, writer Dalton Trumbo, and megastar Kirk Douglas. Kubrick essentially didn’t agree with any of the other members, and his signature input seldom pokes out of Spartacus (despite still being a fantastic film). Otherwise, Spartacus is one of the better epics of this nature, maybe — oddly enough — because of this quarrelling; every person involved tried their damnedest. We all know the iconic “I’m Spartacus!” moment, but even the build up before (and the under-discussed harrowing finale afterwards) are worth the near runtime. Spartacus is solid through and through, even though a number of factors could have led it astray.

98. The Children’s Hour

As solid as Ben-Hur is, I love when William Wyler is focusing on the deepest emotions of humanistic characters. His adaptation of Lillian Hellman’s The Children’s Hour is such an example of this, and an underrated film of his. Despite being tame by today’s standards, the discussion of lesbianism during a bigoted time is right at the heart of The Children’s Hour; underneath the misguided factor of innocence found in a mischievous, naive child. We never really get the full picture, and the “L” word is never even used in The Children’s Hour, but its conversation is made loud and clear. Presented as a difficult conversation where accusers are hateful and the accused are vulnerable, The Children’s Hour holds up, because it shows how the right education of personal beliefs prevent toxic partisanship.

97. Branded to Kill

Poor Seijun Suzuki. Sometimes it just doesn’t help to be so ahead of one’s time in the present. Branded to Kill suffered greatly as a film that couldn’t earn back a profit and garnered no love from critics. Now, I dare you to try and find any mainstream filmmaker with an edge that wasn’t influenced by the insanities found within Branded to Kill. A silly noir yakuza flick, Suzuki’s opus is beyond comprehension, and that is entirely the fun here. Blending danger with confusion and laughter, Branded to Kill is the kind of genre bender that we dream about now. Funny how pop culture works sometimes, isn't it?

96. The Great Escape

It's peculiar how The Great Escape continues to be such an integral film in American cinematic culture, particularly the same circles that tout feel good, triumphant works. In all actuality, The Great Escape’s storyline is far from the success you might expect, but the entire journey -- and what was even accomplished — is enough to be spellbound by. Knowing all of this was true (the execution of the attempted escape from a POW camp) is similarly mind blowing; enjoying these calculated measures bit by bit for three hours is an absolute treat. No matter what, The Great Escape never feels like a letdown or a false promise, because it sets up just how daunting this entire mission is. It remains beloved, and one hell of a story to be told.

95. The Graduate

“Hello darkness my old friend.” The Simon & Garfunkel song “The Sound of Silence” is a bit of a joke now, but back in 1967, it encapsulated all of the “what if?” worries of Americans that had no idea what came next. This includes the titular graduate Benjamin, who is caught in a miserably confusing place in life. The Graduate was incredibly daring for its upfront depictions of grooming intertwined with the existential griefs of the new generation of a society, to a point that it still feels even slightly taboo today. A harrowing moment is the final image, where the impossible has been achieved, and yet the realization that it wasn’t enough settles in. We will forever be plagued by the unknown. Adults don’t know any better than teenagers do. That old friend darkness returns, just when you believed you had escaped it.

94. Alphaville

A visionary like Jean-Luc Godard (whose name you’re going to see a lot on this list) can take everyday Paris and somehow make it feel like the future. Alphaville is a dystopian noir film that utilizes everyday life with enough close ups, odd angles, and occasional embellishments, and we’re left with a world that feels completely foreign to us. Oddly enough, Alphaville is somehow one of Godard’s more neutral fictional films he’s made, because he savours most of his experiments for creating the world; it’s a considerably straightforward effort by the master of the contrary. The end result is a depressing reality where identities don’t matter, and tyranny never left; a semi neo-noir before neo-noir actually existed in full force.

93. Nothing But a Man

Thanks to governmental preservation and the internet, Nothing But a Man is more well known now than ever before. Its importance as an early testimony of the African American experience right at the end of segregation (in 1964) is still felt so strongly. Despite the white filmmakers telling these stories, Michael Roemer and Robert M. Young do their best to let the stars (Ivan Dixon, and Abbey Lincoln, amongst others) do the majority of the talking. Even though parts of Nothing But a Man surround racism, most of the film is centred around the story of men being disappointments, either as fathers, husbands, coworkers or friends. All of that stems from the systemic placement of the characters in Nothing But a Man, and yet that side of the coin remains subtle considering everything. In 2020, this film is a beautiful slice of a much needed voice that still needs to be heard today.

92. An Autumn Afternoon

Right at the end of Yasujirō Ozu’s brilliant career was the swan song known as An Autumn Afternoon: a film still as sublime as anything he ever made. Ozu’s works often discussed the forcible nature of marriage — an otherwise mutually beloved ritual by most (or all) members involved — and this was a topic that was close to Ozu’s heart (he never married and remained at home with his mother, living in a time that wasn’t tolerant of his possible sexuality). Even though marriage felt like a plaguing conversation for Ozu, his films present heavy topics so softly, and An Autumn Afternoon is no different. Shot in lush colours and told with calming voices, An Autumn Afternoon presents the dilemma of being forced into a partnership for life, and dying all alone. Society’s forcible predicaments are never fun, but at least Ozu was the master at making them warm to witness.

91. Easy Rider

The ‘60s were full of counterculture, especially towards the end of the decade for Americans. So, it comes as no surprise that Dennis Hopper’s acid trip Easy Rider was capable of creating such a stir. Featuring a getting high scene with actors actually getting high, the quest for American dreams in different places, and the obscure ending that surely catches everyone off guard the first watch, Easy Rider has zero regard for anyone watching it in true anarchistic fashion. Although a bit of an alienating experience (especially amongst similar works), that only solidifies Easy Rider’s spot in the more rebellious works of pop culture. Yet it still remains as popular as it is. I suppose that sometimes even the more out-there works can leave their mark with the masses.

90. The Lion in Winter

When films with great acting are brought up, I feel that The Lion in Winter is not mentioned nearly enough. Perhaps a massive example of the ultimate thespian podium, this royal domestic drama pits Peter O’Toole, Katharine Hepburn, and a young Antony Hopkins and Timothy Dalton together to watch the sparks fly. Things get incredibly dicey (I’m siding with Hepburn’s Queen Eleanor, who is frighteningly powerful). As arguments continue and personal secrets get stomped on, The Lion in Winter becomes as compelling as any piece of drama you’ve ever seen. As painful as some of this fighting gets, The Lion in Winter is completely exhilarating.

89. The Silence

One of Ingmar Bergman’s hidden gems is the middle film of his unofficial God trilogy known as The Silence. Parts Persona and parts Summer with Monika, The Silence is partially peculiar and completely vulnerable. With two distanced adult sisters and the perspective of one of their young sons, this take on loneliness and bitterness is spiced up with the imagination of the wandering mind, wrapped together nicely with the shadows of a dismal hotel’s hallways. The Silence is smack dab in the middle of Bergman's usual creative processes, as somewhat minimalist and maximalist, creating a strong harmony that will cause you to have double takes (are we seeing what we thought we saw?). For a director as discussed as Bergman, The Silence is criminally under-loved.

88. Faces

At the start of John Cassavetes’ career, he was setting the tone for what an indie picture could be (Shadows, mainly). Keeping true to the stripped down aesthetics of what he was then accustomed to, Cassavetes continued to work within the empty spaces, and Faces felt like the confirmation of this preference. The images are so fuzzy that shadows and light spill into one another like salt and pepper being placed in one shaker. Featuring a couple that begins to date around in spite of both partners involved, Faces feels like the invasion of a private life that simply won't stop prying; it's incredibly uncomfortable. Nonetheless, it’s proof that Cassavetes was always able to squeeze out the indescribable sensations distraught humans feel that many films tried to stray away from; and thus, his signature style was introduced in a big enough feature.

87. Chimes at Midnight

So Orson Welles wanted to make a sillier film. Even that looks and feels amazing. Chimes at Midnight is somewhat of a parody of the works of William Shakespeare, involving the reoccurring character Sir John Falstaff. Welles plays Falstaff in a permanently drunken state, as he just stumbles upon important events in history (and various Shakespeare plays). Even through the stupidity of these predicaments, Welles shoots everything stunningly, as if everyone in the world had to marvel these tales. Maybe it only made complete sense to Welles (it was his favourite of his own films after all). Chimes at Midnight almost feels too good for itself, but that’s kind of why I love it.

86. Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors

Before Sergei Parajanov went fully into the direction of cinematic iconography that he became synonymous with, he still needed to get to that place. He may have written off the rest of his earlier works, but there’s no way something as beautiful as Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors can be dismissed in any way. With more movement and plot than his strongest latter works, Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors feels maybe a bit more digestible, and acts as the perfect bridge from his roots to the future of cinema he was aching to create. With the complexities of love at the forefront (a relationship spawning from vengeance), this Parajanov feature is the most structurally complicated of his classic period. Don’t make the mistake of neglecting this film; it deserves the attention of the other Parajanov opuses.

85. Mahanagar

Shortly after the groundbreaking Apu Trilogy, Satyajit Ray could have gone anywhere with his works. He decided to keep true to himself and continue telling the tales of the struggling lower classes of India. In Mahanagar, no longer is the optimism of the Apu Trilogy present, when family could be proud of the success of another. Instead, we have a wife fighting to make her living and progress as an individual, and a husband who doesn’t approve of this growth. With societal depictions of gender hindering the capabilities of a fighting spirit, Mahanagar is a take on how the “big city” (the film’s English title) is daunting; Ray is here to tell us that it’s the obsession with toxic traditions that makes the city as bad as everyone says.

84. A Woman is a Woman

Just after Breathless, Jean-Luc Godard was already set to be a figurehead for the French New Wave movement. He utilized this opportunity to tell the fleeting A Woman Is a Woman, in all of its pretty colours and silly natures. With its empowering take on a woman’s right to dictate how she is to be perceived (with Anna Karina right at the start of her cinematic takeover), this vibrant early work is just as daring as anything else Godard was making. Outside of its visual aesthetic, why isn’t it talked about? I guess that Godard has so many other films to bring up, but not including A Woman Is a Woman -- especially because of how progressive it is and signature it is with Godard’s renown style — is a travesty.

83. The Gospel According to St. Matthew

Pier Paolo Pasolini’s name is now synonymous with infamy, even though he has also granted us gorgeous films as well. He selected a very specific author in the bible to tell his story of Jesus Christ; obviously, as per the name of his feature, he went with The Gospel According to St. Matthew. His perfect balance of religious gorgeousness and imbedded fear coats The Gospel in a sleek finish; it’s a story we’ve seen time and time again, but not quite like this. Placing the art of film before trying to just make a faith based film, Pasolini subsequently created the strongest cinematic retelling of the life and death of Christ, and I don’t think the contest is even close (outside of, say, The Last Temptation of Christ, which isn’t every Christian’s favourite version).

82. A Raisin in the Sun

Lorraine Hansberry broke ground as the first African American woman to have a play get featured on Broadway, and A Raisin in the Sun was an absolute sensation. It begged to get the cinematic treatment, given how much the Younger family deserved to be seen up close. Daniel Petrie’s treatment did just the trick, and the 1961 film version is a gripping look at an African American family fighting against society’s boundaries. With a fiery Sidney Poitier at the forefront, and ladies Ruby Dee and Claudia McNeil to steal each and every scene, A Raisin in the Sun is a scorching representation of marginalization in America, hoisted even further by acting brilliance.

81. Wings

Known more for The Ascent (which is a perfect cinematic take on guilt in wartime, let’s be honest), Larisa Shepitko may be seen more as a single film wonder more than what she deserves to be recognized as. Straight out of film school, Shepitko made Wings (no affiliation with the William A. Wellman silent film): a hypnotic look at a former fighter pilot’s obsession with flying, despite having had to control planes during World War II. Even though part of Wings is devoted to trauma, much of the visions are also geared by the longing to take part in a passion that has been destroyed by the severances of humanity. Can one enjoy their dream if they lived it for the wrong reasons? Clearly, visual storytelling is what Larisa Shepitko was meant to do.

80. Mandabi

Ousmane Sembène was ready for big things after La noire de…: his first successful feature. He clearly wanted to continue his visual discussions of colonialism in Africa, and the difficulties of living in poverty. He went fully into these topics with Mandabi, and it’s the kind of nightmare that anyone who has ever been tight on funds and in hopes of a dream resolution can attest to. It begins with an event that seems like progress: a money order meant to help clean up the lives of the lead character, Ibrahima, and various loved ones. Instead, promise falls through, and life only gets worse; when it rains, it pours. Sembène never held back on what he wanted to say, but he still treats his characters with the utmost warmth, allowing you to feel every single instance of relatable and sympathetic agony.

79. A Hard Day’s Night

It’s almost strange that A Hard Day’s Night is as good as it is, and it certainly helps add credence to the legacy of The Beatles. It’s genuinely funny and witty, almost to the point that we believe the Fab Four are as blisteringly clever as they seem here, despite having lines given to them. The musical numbers themselves are shot so stunningly as well, as the opportunity to use the popularity of The Beatles to showcase great filmmaking was pounced upon immediately. Acting as a living album (of the same name) and a nod to screwball cinema, A Hard Day’s Night is heaps fun that had much more care put into it than it needed, but I’m thankful for the end result nonetheless.

78. Closely Watched Trains

Czechoslovakian New Wave films are extremely out there (you’ll see more of these films pop up on this list), and Closely Watched Trains is no exception. Likening war time inexperience to a virgin boy’s rampant effort to reach sexual maturation, Jiří Menzel’s strange vision dares to go a little far without greatly jumping over the line. Instead, Closely Watched Trains likes to press its luck, and it achieves just that in a time when Czech cinema was being tested and American audiences were kind of getting used to weirder films on their own end. Closely Watched Trains contains so many of life’s discoveries in a little time, through a hyperbolic vision, and a dark sense of humour.

77. The Miracle Worker

Before he went above and beyond with Bonnie and Clyde, Arthur Penn pulled off the much safer awards season darling The Miracle Worker with great ease. To tell the story of the relationship between teacher extraordinaire Anne Sullivan’s relationship with a young Helen Keller, the film needed the best tandem of actresses at the very front of this picture. Luckily, Penn — who had directed the theatrical version of The Miracle Worker as well — kept his dynamic duo of Anne Bancroft and Patty Duke from that version, and they shine exceptionally bright on the big screen. Delivering two of the best performances of the decade, Bancroft and Duke create the sternness of Sullivan, the tantrums created by fear of Keller, and the tension melting into triumph between the two.

76. The Wild Bunch

It’s obvious to say that Sam Peckinpah is the kind of director that loved to poke the bear, and a revisionist western like The Wild Bunch is such an example of this. Having a beloved Hollywood icon like William Holden start this film off deceiving the audience and even — gasp — threatening murder is the jumping off point of this heist bloodbath. Using the dying ways of the western genre to justify the evil ways of the band of twilight-years misfits leading this film, The Wild Bunch presents outlaws with nothing to lose. It’s a bit different than the safer American westerns of old, but The Wild Bunch still went much further than it even needed to. Consider it futuristic if you want, because The Wild Bunch prophesied how extreme the wild west was going to become in Hollywood.

75. Knife in the Water

Right away, Roman Polanski was churning out golden cinema. His debut film is the only one to be told in his mother tongue of Polish, and maybe succeeding on the very first try was all he needed. Knife in the Water pits a distancing couple and a young, cheeky vagabond all on a tiny sailboat, and sarcastic digs begin to turn into flirtations (if not tension). You always feel like the unnamed third wheeler has overstayed his welcome, or that he shouldn’t have been on this excursion at all. Even with the beautiful sea surrounding us at all times, Knife in the Water just feels uncomfortable at every single second. It was an early sign that Polanski adored toying with the comfort zones of his audiences, and a figurative dipping of his toes to see how much deeper he could go into this lake of dread.

74. Kes

Ken Loach’s coming-of-age film Kes is one of the more devastating looks at the abuse that British schoolchildren endured during the education system’s darker years. Tortured by bullying and the harassment of adults (his father and a teacher, mainly), Billy's only solace is in the form of a kestrel that he teaches to fly. Seeing him finally open up and feel comfortable in his own skin (especially with a teacher that encourages Billy to express himself safely) is an absolute treat. Kes follows this up with the grimness of reality, and that’s sadly why it sticks with you so much. As loving as some people in the world can be, the poison of others can win and ruin all joy. If children are being taught hate, no wonder why adults are so jaded and monstrous.

73. To Kill a Mockingbird

Harper Lee’s literary classic was inevitably going to be turned into a film, and Robert Mulligan’s rendition is likely as good as it’s going to get. Firstly, Gregory Peck as Atticus Finch is one of those acting gigs that is a match made in heaven; to the point that Peck’s other fantastic work is overshadowed by this one stellar role. Mulligan’s To Kill a Mockingbird isn't afraid to get dark either, and that’s very important for creating emphasis on the necessity to discuss the bigotry that is ruining the legal system. Seeing racism through young eyes is hard to pull off authentically, but Mulligan and company capture Lee’s remarkable lessons for younger audiences with complete respect.

72. Satyricon

Where does the critical uncertainty for Federico Fellini’s Satyricon (or Fellini Satyricon, I know) come from? If Pasolini or Jodorowsky made this, I don't think people would even bat an eye. If anything, knowing that the same guy that made La Strada was capable of such an unhinged art explosion like Satyricon is fascinating; it's as if Asghar Farhadi had the same awakening. As it stands, Satyricon is either adored or neglected due to pretension, but its indescribable exploration of classic era literature (specifically the source of the same name by Petronius) mixed with stream-of-consciousness imagery is a cinematic revelation. If 8 1/2 was Fellini trying to cure writer’s block, Satyricon was his unfolding of his subconscious completely, allowing the parts of the mind and spirit that no one dares to visit to be fully explored.

71. The Virgin Spring

The first Academy Award that Ingmar Bergman ever won ended up becoming more famous for being the source material for I Spit on Your Grave. It's unfortunate, because The Virgin Spring is much more than a rape/revenge exploitation flick. In ways, it is one of Bergman’s most upsetting experiences, where his usual conversations about faith and the sickness of humanity are as bleak as ever here. The dealing with its upsetting subject matter is considerably delicate without losing too much of the monstrosity that sexual assault and murder carry. So, the decision to fatally reprimand these creeps by a father who has lost his daughter in extreme ways becomes much more of a discussion: what is the right course of action here? The Virgin Spring is leagues beyond the genre it has become linked to, and it deserves to be remembered differently.

70. Weekend

Jean-Luc Godard has so many films that can be considered fashionable, but somehow Weekend keeps getting right to the forefront of his legacy. Maybe Weekend is the first Godard film people see of his, and that could explain it. It starts off considerably more normal than his other iconic works that reveal their twisted ways very quickly (although it’s still off enough). However, it progressively gets crazier and crazier, with the plot completely being abandoned for a little while, before returning in an incredibly sadistic way. It’s like a slow descent into Godard’s madness, unlike any of his other classics that are more honest right away. Cinema was once considered unfit for the upper class to stoop down to, and many works since have mocked the bourgeoisie. Weekend feels like a rare instance where it aims to bait the elite, then completely desecrate their confidence with gore, mockery, and — worst of all — a lack of conventional structure.

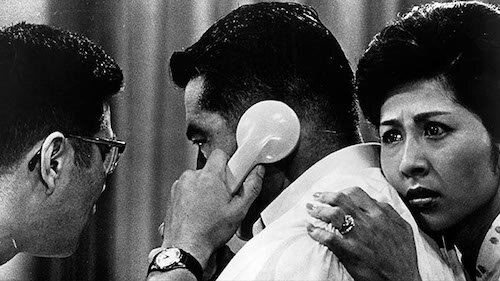

69. In the Heat of the Night

1967 was a breakthrough year for New Hollywood, and the Academy Awards knew it. In the Heat of the Night won Best Picture, becoming a massive statement for what was to come in cinema ever since. Even if you strip the racial commentary away from the film, it dared to be so far ahead of whatever police dramas came before it, with Quincy Jones’ experimentation of noises in his score and the toying of pacing. Norman Jewinson’s aware direction allows the showdown between Old Hollywood (Rod Steiger as a bigoted white chief) and the future (Sidney Poitier as a black officer) to really speak volumes on the state of the industry. Then, reapply the commentary and In the Heat of the Night is a vital statement on insensitive perceptions created by racism, as officer Virgil Tibbs — who could have solved this crime ages ago — has to fight against both racism and time in this procedural thriller for the ages.

68. Two Women

Even though Vittorio De Sica is known for his depressing works of Italian neorealism, Two Women starts off with some sort of promise. A mother and daughter flee a war torn Rome, and end up living a new life in Ciociaria. The mother (played by Sophia Loren) has so much likeable sass to her, and you feel safe by her side. Sure, there is some tension between her and her individualistic daughter, but this is a film all about starting new, right? That’s when De Sica gets you, and it hurts so immeasurably bad. Two Women’s true intentions only get revealed later, and you can easily qualify it as one of De Sica’s devastating works. The final act is all about being there to heal a loved one during trauma, even after a separation, and it changes every single ounce of growth shown before it.

67. Gertrud

To be Carl Theodor Dreyer’s final film really means something. Dreyer was a major director from out of the tail end of the silent era who was already set on pushing the limits of the end of an age. He continued his artistic visions even well into the decades of sound pictures, and never eased up for one minute. Naturally, his swan song Gertrud was as aesthetically adventurous as anything else he had ever made, turning a play about a marriage destroyed by a new lover into an artistic exploration of the heart. Long takes, reflections, and poetic passages all slice Gertrud up into a series of risks for 1964, which separated audiences. Now, Gertrud is inexplicably gorgeous, and, as per usual with Dreyer, so ahead of its own time that the world just wasn’t ready for it (even though Dreyer was making films for many years at this point).

66. The Manchurian Candidate

Cold War epics were sure to be made at any given time, so The Manchurian Candidate didn’t exactly come from nowhere. However, starting off with its dream sequence was quick evidence that this political thriller wasn’t going to feel like your usual fare. The Manchurian Candidate exists almost solely in the mind, even if we’re not being hypnotized or stuck in a sleep state; the real world looks as off as the perceived world. For all of the film, you feel disoriented; you’re itching to solve the espionage weaving at the same time. The Manchurian Candidate cons you so easily, even before you get emotionally invested; by the climax, you’re completely doomed, sweating with worry. A film as smart as The Manchurian Candidate rarely aims for the heart, too. You're bound to be mesmerized.

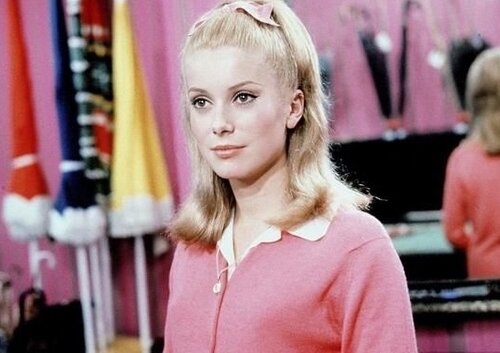

65. The Young Girls of Rochefort

After The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, Jacques Demy could have gone anywhere with his musicals, given how this film was a heart melting opera with so much colour and life in it. Instead, he wanted to go right into the same folder as his inspirations and make one of those good ol’ Hollywood musicals, like An American in Paris. He reunited with Catherine Deneuve, and brought her real sister Françoise Dorléac in as well. He even went far enough to hire that very American in Paris — Gene Kelly — and had him really tie the film together in exactly the same way he always does. The Young Girls of Rochefort is pure musical escapism with a pinch of the Hollywood old and a lump of Demy’s new Parisian way. There is very little drama, but all of the love and joy in the world.

64. Kwaidan

Masaki Kobayashi loved to tell stories, but he seemed to prefer releasing more than one at once (see The Human Condition). So, Kwaidan makes perfect sense as a series of horror stories told like an anthology book to be read at bedtime (by daring children). However, Kwaidan is absolutely not for kids, and Kobayashi’s vision is able to really freak out adults of all ages (trust us). The beautiful cinematography transports you to dreamscapes and living picture books, and it’s unfortunate that all of the ghastly imagery leaps right at you while you’re vulnerable. It really seems like Kobayashi adored to tell these tales, like one of those amazing kinds of campfire readers. To have that in cinematic form is bliss.

63. Ivan’s Childhood

So it seems that Andrei Tarkovsky is the first filmmaker whose entire feature filmography has made my lists of the best films of all time (let’s see if anyone else is able to join him). Even his very first film, Ivan’s Childhood, is pure cinematic poetry at its finest. Not quite as abstract or empty as his existential opuses, Ivan's Childhood is still artistic enough to be impossible to turn away from. Placing the titular child in a harrowing World War II backdrop allowed Tarkovsky to frame the horrors of the world in a whole new way. We’re closer to the ground, destroyed structures loom even higher, and evils feel even scarier. Even from the very beginning, Tarkovsky was clearly born to make films. The fact that Ivan's Childhood is arguably on the lower end of the rankings of his filmography is borderline miraculous; this would be the greatest achievement of many others.

62. The Housemaid

Much before the millennium wave of Korean thrillers, something like Kim Ki-young’s The Housemaid is enough proof that Korea was always the epicentre of brilliantly twisted narratives. The cunning ways of the titular housemaid and her burrowing into a family that has hired her is enough of a spectacle. Then, the comeuppance of unfaithfulness, deception, and corruption spices everything up. There is absolutely no way The Housemaid ends nicely, but even then it’s impossible to be fully prepared for how it completely unravels. As if this was written in 2000 instead of 1960, The Housemaid is so current with its labyrinth of lies and hidden intentions.

61. Mouchette

If there was ever a director that could create the most depressing films of all time, it would have to be Robert Bresson. The first example for this claim is Mouchette (his most devastating case is higher up on this list). I view Mouchette almost like the anti 400 Blows, where a young child discovers a world for themselves. In the latter, mischief is the primary reason for the protagonist’s grief. In Mouchette, there is virtually nothing the titular character could have done differently to protect herself from a disgusting world. To watch Mouchette is to understand the death of innocence, and the dissolving of the will to want to live amongst such monsters. It’s Bresson’s antithesis to French New Wave, and, well, it hurts.

60. The Leopard

Right at the tail end of that wave of super epics that dominated the ‘50s is Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard: a sweeping tale of the shifting tides of politics in nineteenth century Sicily. Starring three icons that speak their own language (Hollywood’s Burt Lancaster, Italy’s Claudia Cardinale, and France’s Alain Delon), The Leopard was concerned with capability more than realism (everyone was dubbed over anyway, as was common with Italian filmmaking at the time). Apply this attention to effort in every single way, and you get lavish sets, gorgeous choreography, and a constant flow of emotions that pour off the screen. The Leopard ends so simply for a film this gigantic, allowing even the smallest images to carry their own weight after such a journey.

59. Wavelength

When I eventually list my top short films, I’m going to be using the guideline of around forty minutes or less. That means Michael Snow’s experimental classic Wavelength makes the cut; guaranteed it's going to feel more than forty five minutes for many readers. Having a slow, constant zoom into a single room is already an excellent statement on spacial relation in film; having the end result be a landscape image zoomed into to destroy barricades is something else. Toss in the brief vignettes that have zero meaning outside of disrupting harmony, and you have an avant-garde gem. The frequencies become harmonious and the distorted image transforms into a hallucination. I can't wait to discuss more experimental films in my shorts list, but Wavelength deserves appreciation as a challenge that is accomplished in feature film length.

58. Rosemary’s Baby

Doesn’t pop culture suck sometimes? As much as it is fun to identify with others, certain stories get spoiled because of their overall impact. Almost everyone probably knows what Rosemary's Baby is all about; imagine watching this film without even a hint as to what will happen. Either way, Roman Polanski’s demonic horror classic is still magnificent to watch with its biggest secret being spoiled to the world. The gradual descent into madness is still shocking, and the build up to get there remains chilling. In a decade where comfort zones were being tested, attacking the bond a new mother has is beyond sadistic. And thus, one of cinema's most terrifying flicks was born.

57. Yojimbo

Although I don’t have A Fistful of Dollars here (a fine spaghetti western film indeed), that might be for one major reason. As exciting as it is, its source material, Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, is better. Instead of being fun, it’s unpredictable, and the titular bodyguard — Kuwabatake Sanjuro — feels much more in danger than The Man with No Name (more on him later). Yojimbo is full of desperation, between a village that is in danger, and a lone wolf that has been replaced as the primary target. Much of the film is a daredevil act of walking on eggshells, waiting for your next step to break your platform. Then Sanjuro strikes, and Yojimbo subsequently takes your breath away. Even after countless samurai classics years before, Kurosawa still had his knack for them going into the ‘60s.

56. Bande à part

As crazy as Jean-Luc Godard films got, few of his narrative features felt as completely anarchistic as Bande à part. For once, it didn’t seem like Godard was breaking film apart for us. It felt like Bande à part destroyed itself, and it’s glorious. At times, the film is of a different dimension for it; the jukebox dance could go on forever and I wouldn’t mind. In other capacities, it almost becomes hilarious; the very ending feels like we’re wrapped up a Disney romcom or something. With very little regard to genre conventions, Bande à part is blatantly different, hence why it’s often one of the first Godard films people jump right into. Godard has been more daring and more moving, but Bande à part is the most relentlessly Godard of any of his fiction films.

55. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance

The ‘60s were eager to finally say goodbye to the American westerns of old, and I don’t blame the decade for getting ready to move on. However, one last classic western felt like just the ticket, and there was no better director for this particular job than John Ford. We know Jimmy Stewart and John Wayne starred in other films after The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, but seeing them here for one last hurrah with an American filmmaking legend was just what the world needed. The concept alone was enough; it helps that Liberty Valance is a phenomenal film through and through. Even with the revelation of events right at the start of the picture, you can’t help but be glued to the inner-town bullying and politics that drive Liberty Valance. It’s the very end of a genre done right, especially when revisionist and spaghetti westerns were here to stay.

54. Divorce Italian Style

Years before Hollywood was ready to have a similar conversation, Pietro Germi was proving what American cinema was missing with Divorce Italian Style: a viciously dark comedy about the impending dissolving of a marriage in the worst ways possible. Instead of trying to find love in one’s heart for a partner they once adored, Ferdinando is willing to go through great lengths with disastrous consequences to be able to be with someone else. Marriage Italian Style begins like a series of terrible ideas, before Ferdinando actually begins to go through with what’s on his mind. Luckily, we’re kept at a distance, despite being trapped in his mind, so we can watch this insanity from afar and either laugh or gasp. Holy matrimony wasn’t meant to be this disturbed.

53. Late Autumn

The first film of Yasujirō Ozu’s career was a sign of something new in a filmography that was consistently evolving without losing a sense of the late filmmaker’s singular style. Does Late Autumn contain family and marital discussions? Yes. Does it contain solely static shots, most of which are taken closely to the floor? Yes. However, even with all of this in mind, Late Autumn takes Ozu’s tropes and goes a little bit further. Opening a decade where safety in cinema would start to crumble, Ozu gets as cynical as he would ever be, with the occasional confrontation; within his iconic framing, Late Autumn almost feels like a domestic disruption within your own four walls. Still, Late Autumn is an Ozu film through and through, and it’s mostly a stunning film full of spirit and optimism; its darkness doesn’t last very long.

52. Wait Until Dark

Taking place mostly in one room, Wait Until Dark is deceptively minimalistic, leaving the impression that only so much can happen. With a recently blinded housewife trying to fend for herself when intruders attack her home, the feeling of desperation rises insanely quickly; seeing that same housewife succeed in outwitting these chumps is a triumph in and of itself. That’s when Wait Until Dark decides to play mean, by upping the ante and getting considerably scary; I dare you to remain completely comfortable throughout the final act. A thriller with so much tension that is comparable with what todays films can give, Wait Until Dark is way too underrated at this point. The fact that it isn’t brought up even more, given its mastery of uneasiness and fear through dramatic irony, is terrible.

51. Pierrot Le Fou

Escaping the world with Jean-Luc Godard is a bit of a double edged sword, and Pierrot le Fou is evidence of this. On one hand, you enter a cinematic realm that feels so unique, as is the usual case with Godard (colours are so striking, editing stands out, and time barely exists). On the other, you have an island getaway from the entire world that results in anguish and bitterness taking a hold on everything. As lavish as Pierrot le Fou is, it’s also incredibly cynical, almost in a sadistic way. As love gets torn apart, so does the film in a conventional sense, and Pierrot le Fou is like watching Godard take his beloved romantic film that’s failing out back to put it out of its misery. That’s Godard for you.

50. Through a Glass Darkly

Right in the middle of the Ingmar Bergman spectrum of films (realistic existential dramas or dramedies, and psychological horrors) is Through a Glass Darkly: a rare instance where Bergman holds back on how much of a character’s mental struggle we actually see. For once, we’re listening and observing more than we are taking part in, and it’s almost scarier that way in this morbid tale of seeing a loved one slowly disappear mentally, only to succumb to illness. Through a Glass Darkly takes a relatively neutral approach, so we never condemn what takes place, no matter how terrible these events may be. We can only hope and pray that things will work out, even in these darkest hours.

49. Repulsion

When it comes to surreal horrors, it seems as though Roman Polanski was way ahead of his time with Repulsion, which continues to resonate with audiences today. The overtaking of nightmarish images in the mind of a woman experiencing a sexist, misogynistic world only feel more appropriate, the more the world discusses and tries to rectify its problematic ways. Just as a straight up horror, Repulsion really does the trick more than many other psychological thrillers, given the fantastic use of shadows, silence, floaty spacing and bizarre designs. When reality begins to blend into the subconscious, that’s when Repulsion truly shines (or, well, remains extremely dark) as we watch the straw break the proverbial camel’s back.

48. Vivre Sa Vie

It wasn't rare to see a more emotional side of Jean-Luc Godard (another entry coming up is an additional example), but it’s still fascinating to see, given the unjust reputation he has for being weird or provocative. Vivre sa vie takes a woman’s deteriorating life (from workplace woes to marital abandonment) and chops them up into twelve chapters, as a means of making this tragedy more digestible. News flash: it’s still harrowing. To see Nana’s life wither away as she fights to survive in any which way is so difficult, until you really see what Godard can do with the form of a film. With the confinements of what cinema can allow, Vivre sa vie goes as far as it can, and that's half the depression; you know in Godard’s mind, this couldn't have been saved in any way.

47. L’Eclisse

Being the worst part of a hypothetical trilogy and showing up this high on a list isn't so bad. Michelangelo Antonioni had a hell of a decade even outside of this triptych, but it’s how well L’Avventura, La Notte, and L’Eclisse work together that resonate the most of his golden period. L’Eclisse takes the concept of a lunar eclipse and applies it to romances (how someone can overshadow a loved one and steal their light). In typical Antonioni fashion, the film is invested in the time spent with another more than just delivering a plot, so moments gestate a little bit more organically. Once we're given a dilemma to solve, we can only have our own solution before L’Eclisse hands over its own, reminding you that it was always going to do what it wanted anyway. As a statement on uncontrollable love, L’Eclisse is a unique final say in a trilogy full of new approaches to how adoration can be achieved in cinema.

46. Jules et Jim

Not many cinematic love triangles can come even close to what François Truffaut achieved in his film school staple Jules et Jim. Even when both title characters fall in love with Catherine, they still respect one another as inseparable friends to a degree. Truffaut uses this unique approach to really explore what relationships each character holds with each other and themselves, in a world being devoured by war, loneliness, and expectation. Truffaut’s expertise on finding poetry in the unknown is what propels Jules et Jim even further than its already strong premise, and it makes for an incredibly unpredictable journey into the human experience, where love can blind self aspiration and life itself.

45. Midnight Cowboy

Boy, were the late ‘60s in American cinema strange. Midnight Cowboy remains one of the more out-there winners of the Best Picture Academy Award, and the only X-rated film to win (well, by today's standards, Midnight Cowboy is very soft). A cowboy, washed up by the macho influences of commercialized America, heads over to New York, New York to become a gigolo, only to find himself at the very bottom of the capitalist totem pole. His fight against the system is a hideous one, with Midnight Cowboy’s experimental influences leaping out into the forefront to convey the disjointed nature of a seemingly cohesive America; not everyone is a part of this dream.

44. Le Samouraï

When The Man with No Name was kicking ass and not taking any names, Jean-Pierre Melville conjured up his own version of this rising silent, lone wolf warrior in Le Samouraï. Instead of Eastwood, he had Delon, whose character actually had a name (Jef Costello). Costello found himself in a grey, drab world driven by crime, and his own life fell in the same predicament (as he is a hitman, not by choice). To feel Costello’s slowly grating existence is part of what makes Le Samouraï such a singular experience. To have him try to get out of this life (either literally or figuratively) helps the film break out from a neat experience, and evolve into a passionate letter to the gangster genre.

43. Peeping Tom

Sometimes, it's the artist who has been celebrated by society that breaks apart from the blueprints of the medium the most. As one half of the iconic Archers duo, Michael Powell had virtually nothing to prove when he opened up the decade in a way that seemingly no one was prepared for. Peeping Tom ruined his career, because it sprinted when Psycho ran. The world wasn't ready to see Powell’s unflattering depiction of artistic desperation, or his preliminary entry into the then-non-existent slasher genre. Wasn't it obvious what someone like Powell was always ahead of the game, particularly with his bold ‘40s works? We can appreciate Peeping Tom now, but audiences back then that were already familiar with Powell’s history should have known better.

42. L’Avenntura

In Michelangelo Antonioni’s unofficial trilogy of unique takes on romance, L’Avenntura feels the most literal, with a missing person being quickly replaced during the search for her. Still, the way Antonioni goes about this changing of arrangements is so careful. The build up to each and every stepping stone is thought out enough that all thresholds are effective. Every character actually matters. Do we remain hopeful in this search, or do we hope this romance blossoms? Antonioni is great at mimicking life in his films, and L’Avenntura appears to keep going even when we're waiting on resolution; life has its own plans. Named after the adventure where the disappearance occurs, L’Avenntura is also named after the leap into the unknown, against better judgements.

41. Cléo from 5 to 7

Agnès Varda’s magnum opus Cléo from 5 to 7 is a top-to-bottom cinematic blessing: a part Left Bank and French New Wave mutt that acts as a bridge between both film movements. The titular Cléo believes she is going to die because of tarot cards (which also act as the opening credits: something Varda has always specialized in), and we continue with her towards what may be her final hours alive. Varda’s films kind of just exist, even with their eccentricities, and Cléo from 5 to 7 is no exception; it floats like a spirit through the wrapping up of a lifetime, as a means of enjoying everything that came before one’s demise. This film is an appreciation of what we have in the meantime, and it explores ‘60s cinematic capabilities with exactly the same enthusiasm.

40. My Fair Lady

The ‘60s contained a number of musicals which unknowingly became the last cases of a seemingly dying breed; nothing was done to try and wrap it up until directors like Bob Fosse scrambled to do so in their own way in he ‘70s. Otherwise, the showtime, theatrical musical that we once knew as a frequent genre of film, was on its way out. One of the great final hurrahs was by the master himself George Cukor, and his version of My Fair Lady is an uplifting, magnificent experience. Taking part in the transformation of Eliza Doolittle is a fantastic play on the human voice as an instrument; diction lessons and musical numbers go hand in hand. My Fair Lady is stunning to look at, magical to behold, and three hours that blow right by you. As an accidental figurehead for the end of an era, My Fair Lady resonates for the musicals of yesteryear perfectly.

39. Playtime

Can a comedy be overly ambitious? It may have seemed that way when Jacques Tati took his Monsieur Hulot character’s misadventures to a whole new level with Playtime, where every single image of this three hour, mostly dialogue void comedy is a series of visual gags happening at the same time. It’s actually virtually impossible to catch every joke, reference, or illusion on the first watch. If anything, we find ourselves laughing less than we get completely sucked into this world that feels oddly familiar (although we do laugh a lot here). Hulot himself takes a step back for Playtime as a cinematic world to shine, and this includes Tati as a visionary being seen in full effect as well. If there was ever a carefree film where you could visit for long periods of time and feel something new every time, it’s Playtime.

38. Eyes Without a Face

Georges Franju held onto the artistic horror films that Europe was dishing out in the ‘50s long enough to introduce a new decade to Eyes Without a Face. This film seems to exist in a universe of its own, moving slowly like a series of apparitions with grizzly detail. Is it right for a father to do anything for his daughter and her wellbeing if it affects the lives of others? What about to the extent that takes place in Eyes Without a Face, where surgical experimentation is a frequent occurrence? The stillness that holds all of Eyes Without a Face together feels haunting, rendering all of the images either painfully unsettling or peculiarly exquisite.

37. Belle de jour

In the ‘50s and ‘60s, Luis Buñuel created dramas that were mostly realistic but either flirted with the idea of absurdity, or distanced themselves as unique premises. Belle de Jour falls in the latter category, as one of Buñuel’s normal films (which is still driven by imagination). A housewife's double life starts to head into troublesome territory very quickly, but Belle de Jour heads as far down into this worst case scenario as possible. On a literal level, this film gets incredibly frantic, as vulnerability is stretched to their complete limits. Then, Belle de Jour gets more figurative when it resolves (Buñuel couldn’t help himself), dissolving all of the previous events into one concoction of resolution: a realization that will plague us forever.

36. Army of Shadows

Even in an era like the ‘60s, the works of Jean-Pierre Melville felt so aesthetically advanced, like he was pulling from art waves that everyone else had yet to discover at that point. On that note, Army of Shadows is a unique case in his filmography, because there was a good chance you didn’t see it until decades after it was created (you can thank programmers for reacting to the events of May 68 for that). Finally accessible in the ‘90s and afterwards, Army of Shadows’ bleak, brooding ways almost felt right at home in an era it didn’t even belong to. Its unforgiving resolve definitely felt too soon in a France that was recuperating, so maybe it was for the best that it was unleashed on the world at a later date. Besides, fantastic art will never die; any time is the right time for Army of Shadows.

35. The Apartment

After years of filmmaking brilliance, Billy Wilder had to wrap up at some point. He had a few films in the ‘60s and afterwards, including The Fortune Cookie and The Front Page, that are worth watching, but clearly his last masterwork was the Best Picture winning The Apartment: a magnificent allegory of the middle class’s sacrifice of themselves to continue living, whilst subsequently living less. In the capacity of his entire filmography of classics, something about The Apartment continues to rest in the hearts of many cinephiles. Its tender approach to the dramedy genre and the communities it is highlighting is likely why; not being mocked but being a part of the humour is always welcome. We’ve all been in situations where we’re working and trying to progress to stay alive, and it consumes our identity. The Apartment knows this, and respects us.

34. Les Bonnes Femmes

Out of all of the French New Wave classics of the ‘60s, Les Bonnes Femmes feels a little overlooked. Claude Chabrol’s glitzy vision of nightlife and leisure is stricken by maniacal comedy and complete shock, blurring the film as a slightly saddening affair. Sure, many New Wave films explored abstract embodiments, but Les Bonnes Femmes still feels like it is speaking a different language, especially considering Chabrol’s obsession with juxtapositions. Moments exist less for their own benefit than they do for others, making Chabrol’s vision a running river of vignettes that somehow all correlate beyond boundaries. It even begins and ends as such, turning our lives before and after watching Les Bonnes Femmes part of the experience.

33. Blow-Up

Usually, a filmmaker creating a work in a different language is more cautious or aware of their entry into a new territory; some jokes, ideas or imagery from one culture may not fully translate well in another’s. Well, Michelangelo Antonioni couldn’t have cared less about all of that when he made his English language debut Blow-Up. If anything, this film injects Antonioni’s fascination with voids even more than usual, and slices up the entire narrative into vignettes that really have very little to do with one another. Each and every little segment of Blow-Up is strong for their own reasons, like a smorgasbord of arthouse filmmaking. Nevertheless, whether we’re investigating a possible murder, getting wrapped up in a rock concert, or stumble upon a tennis match played by mimes, Blow-Up takes the cinematic medium as a storytelling device and shakes it up completely. How’s that for an entrance?

32. The Naked Island

By 1960, the concept of a dialogue-less film seemed a little insane; wasn’t decades of silent cinema enough? That didn’t bother visionaries like Kaneto Shindo, who wanted to tell stories like The Naked Island. You're under the spell of Shindo’s fable for an hour and a half, and there isn't a single spoken word that could change anything (the very rare instance of dialogue in this film is mostly for environment building purposes). Instead, we get involved in the life of a family that lives away from the rest of the world, and we get entangled with their daily occurrences. That means any major event hits even harder, and The Naked Island doesn’t shy away from tragedy. Like experiencing the lifetime of someone, an entire family, a society, and the world within a brief amount of time, The Naked Island is poetically arresting, and evidence of minimalism used wisely.

31. Daisies

When the Czech New Wave movement was taking off, the world was given viciously different stories (part of the charm of said movement). Then, Věra Chytilová decided to take things further, as if she mixed the Czech and French New Wave movements and made a rebelliously singular experience like Daisies. Technically, the film barely exists as a narrative, outside of the mischief of the two leading ladies that riot against Czechoslovakian politics, toxic masculinity, and the common cinematic language. Barricades are broken on a consecutive basis in Daisies, less like a dream and more like psychic teleportation, telekinesis, and mind reading. Daisies is mightily nonconforming.

30. The Umbrellas of Cherbourg

When the Hollywood musical was starting to find its way out, someone like Jacques Demy couldn’t stand having their favourite genre die. He went full force with The Umbrellas of Cherbourg: a full on opera that doesn’t let up for one second. Infusing musical tropes with life, Umbrellas feels like an internal monologue sugar coating everything else that is truly going on; we can imagine the events here happening without singing, but I prefer them as is. Without going too overboard on the glamour, Umbrellas is wholesome and touching, but it stays levelled, even in its music heavy capacity. You don’t get blown away by The Umbrellas of Cherbourg as much as you are held by it.

29. Z

We might take it for granted, but having a film speak a little too much about the corruptions of the world in 1969 is really risky. Well, we needed voices like Costa-Gavras to clear the way for political thrillers like Z to really speak their opinions. Well, Z hardly cares about what governments thinks of it, but it would like audiences around the world to hear its warnings about the assassination of Grigoris Lambrakis (even if the film swaps some names around). Consider how quickly after this crisis Z was released, and how much it was willing to share about the inner workings of a faulty Greek government. Yes. It takes a lot of guts to put out something like Z when it exposes enough of a world many of us don't see.

28. The Great Silence

What happens when you mix both the ‘60s signature types of westerns (revisionist and spaghetti)? You’d get The Great Silence: easily Sergio Corbucci’s greatest achievement. Representing the brutality of the murders of voices of change, The Great Silence places a mute protagonist in the middle of The Great Blizzard of 1899 to fend for himself. We slowly follow both him and a gang of outlaws, to see both unstoppable forces collide. We’ve seen this story before. All westerns go the same way. Well, not if you’re daring like Corbucci. The Great Silence carves its own path, and is guaranteed to leave you out in the cold. Westerns aren't supposed to go this way, are they? That was precisely Corbucci’s plan, as he aimed to bowl audiences over in a way that mimics true sorrow.

27. Marketa Lazarová

When the Czech New Wave movement opened doors for artists to get as creative as possible, it’s strange that František Vláčil took a bit of a step back to see what he could do. Marketa Lazarová is almost courageous in how much it relies on itself and not the wave itself. Still, despite having roots in the Czech cinema of old, Marketa Lazarová is artistic enough to stand out amongst the Czech films of the time, If anything, it feels all the more damned: it’s tethered in foundation, and aesthetically expressive. For this dark ages transition from paganism to christianity, that means a hell of a lot thematically; having both constraint and rebellion is exactly what this kind of tale calls for. In scope, length, vision, and its core, Marketa Lazarová is an epic, and one of the most riveting medieval films imaginable.

26. Au Hasard Balthazar

If I had to pick the most depressing film of all time, here it is. Robert Bresson would revisit this damnation of a young figure in Mouchette, but that film felt generous in comparison to the earlier Au Hasard Balthazar, which pits together a child and a work donkey against society’s despicable ways. Watching either storyline is rough enough, but having both work in tandem is borderline savage. Well, if there was ever a symbolic way to represent the abuse of the working and poorer classes, it would be Bresson’s suffocating take on the works of Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Luckily a short hour and a half, Au Hasard Balthazar feels like you’ve taken on lifetimes of grief once you’re finished.

25. Contempt

Potentially the most beautiful film Jean-Luc Godard ever concocted, Contempt is a love-hate letter to cinema and human connectivity. So much of the film is spent on the failure of a marriage during a production, replicating the severance between bonding and following one's dream. Plus, who wouldn't want to work alongside Fritz Lang (who stars here as himself)? Contempt spies on these confrontations with extreme scrutiny, abusing the capabilities of the cinematic lens. It goes one step beyond and frames absolute devastation with the utmost fondness; this is what art can do when used a specific way. So, is Contempt disingenuous, or was it upfront this entire time? Like people caught in a crossroads, film can also lie to your face when it's not baring its soul.

24. The Exterminating Angel

It can be difficult to rank all of Luis Buñuel’s surreal jabs at the upper classes, but they all vary enough to make it doable. For instance, The Exterminating Angel is a slight anomaly. At least here, Buñuel gives his trapped aristocrats the chance to find food and/or water (to a degree). Actually, that might make it even more sinister; that hope will do anybody in. Surreal enough to make the claustrophobia feel overbearing, The Exterminating Angel still seems like a satire more than a torture device. It's the double edged forgiveness at the end that proves Buñuel’s extreme distaste for the elite, particularly the comparison with sheep that was alluded to before (but is used in full effect now). The Exterminating Angel is a borderline thriller, as we watch the rich decimate each other to survive with comfort.

23. High and Low

Even though Akira Kurosawa was known for his samurai epics, his occasional contemporary films deserve all of the love in the world. High and Low is thankfully being discussed more now, thanks to the internet and preservation. Kurosawa’s attempt at a noir thriller is a constant influx of anxiety, with your eyes darting everywhere for vantage points and clues; all we get is a reminder of privilege, overlooking an unsuspecting community below. With the use of elevation and descension used so cleverly, High and Low pits different classes together to solve a kidnapping case. Even when enough feels accomplished, Kurosawa goes the extra mile to dig deeper and go right to the furthest edge of his creation. This includes the limits of sanity, and the desperation of the poor versus the power of the elite.

22. La Notte

In a decade that he seemingly dominated, being Michelangelo Antonioni’s opus is quite an achievement. La Notte is easily his greatest experiment with both shifting notions of romance and the valuing of empty spaces in life, as lives change over the course of one evening, seemingly in the depths of one's heart. Jeanne Moreau and Marcello Mastroianni are placed in a predicament where they are facing ones death before their opportunities to expand on their own lives. Like a dream, La Notte feels like it drifts so far out of one's grasp; we couldn't stop what is unfurling even if we wanted to. Should we even be trying to stop these blossoming events? Then, the sun rises, exposing all, allowing all parties to confront each other about their new predicaments going forwards. There's no emptier, more romantic time than the wee hours of the morning.

21. Bonnie and Clyde

It took a borderline B-movie that had little faith towards it (outside of those who worked on it) to put a nail in Old Hollywood for good. Bonnie and Clyde really had zero regard for how it would be perceived in relation to the ways of old. Full of innuendos, bloodshed, and deliberately broken rules, Arthur Penn’s biopic was the loudest introduction to a new movement in American film history. Taking a tale of American lore and turning it into an exposé of cinematic taboos worked so well, considering the subjects at hand (two lovers and their gang that went against everything). To really seal the deal, Bonnie and Clyde wraps up with an exaggerated scene of carnage: one that still feels sick.

20. I Am Cuba

Ever the auteur to make a political statement, Mikhail Kalatozov decided to make a handful in his vignette driven spectacle I Am Cuba. Featuring camerawork by veteran cinematographer Sergey Urusevsky (which remains some of the greatest images in cinema even still), this multiple-perspective affair aims to encompass all sides of a country divided by politics, and united by cultural beauty. In a sense, having all four drastically different stories smushed together makes I Am Cuba relatively vague, but this also renders the film the embodiment of all; no one is a prioritized character, and not one message about Cuba here takes precedent. To think that I Am Cuba could have vanished with the collection of lost films over time, had there not been a massive push for its preservation, especially with how ahead of its time it truly was.

19. La Dolce Vita

Something about Federico Fellini compelled him to tell stories full of vignettes from time to time; maybe it was his way of getting all of his thoughts into one piece. The time his fascination worked at its best is La Dolce Vita, which collects so many images of the upper class societies of Italy into one adventurous narrative. With dazzling images that don’t make literal sense, we get the aura of sightseers travelling around and pointing out what they say (they may be a floating statue of Christ, or a beached sea creature). There are many points in La Dolce Vita, rather than the film serving one singular purpose. Flipping through these images and sounds is an absolute luxury, like Fellini is lending us the sensation of the high life (and more).

18. Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

To be donned one of the greatest satires of all time really has to mean something. Well, Stanley Kubrick’s parody of how the world is run holds up as a definitive satire, mainly because we’re still run by idiots, and have been ever since. All we see is the carrying out of one plan to destroy a country because of sexual ineptitude (come on) and the aftermath that follows; this leads up to the destruction of the entire planet. In between both events is a parade of fools (with the occasional sane person, mainly Capt. Mandrake) that worsen the situation more and more. With politicians feuding like a married couple, a missile ridden like a horse, and a miracle right at the wrong second, Dr. Strangelove is full of stupidity that still hits a little too close to home.

17. Viridiana

Being Luis Buñuel’s most serious film (or one of them, at least) is a bit of a strange honour. He still feels connected to the unnatural enough to spice up his feature in peculiar ways. Viridiana is the poisoning of the clean, with a nun in training passing off as the ghost of her uncle’s dead wife; he seeks this opportunity to repent his own life, subsequently ruining hers. Not unlike other Buñuel efforts, Viridiana goes off the rails ever so slightly to create a spiritual, surreal uneasiness; the third act’s many broken rules (including that darn fourth wall) are evidence of this. Feeling cinema being torn apart in the same way that one’s spirit is is incredibly difficult, but Buñuel makes it work.

16. Last Year at Marienbad

Alain Resnais might be the greatest conjurer of cinematic memories in the entire history of the medium. Looking at his entire filmography would suggest this, but really watching Last Year at Marienbad is enough. Revisiting the same story and locations countless times with slight variations seems tedious, but Resnais’ approach is so moving that you won’t ever want to leave this dream place. With countering recollections bombarding one another, Last Year at Marienbad is the competition of fondness, as a means of remembering the right way (is it by being true to facts, or true to one’s self?). What is maybe the biggest achievement is how the film never feels like it is haunting us, despite its otherworldly feel; these images are spun through longing.

15. The Color of Pomegranates

Discontented with the films he was originally making (more straightforward dramas), Sergei Parajanov tried to pave his own path. His second attempt at this was The Color of Pomegranates, which deconstructed the cinematic language so greatly, that films still haven’t caught up today. Creating tableaus in the form of living iconography, Parajanov pieced together the most unorthodox biopic of all time: a wholly symbolic look at Armenian ashugh Sayat-Nova. Creating androgynous depictions of the poet, religious visual connotations, and repetitive choreography, The Color of Pomegranates feels more like a ritual than a narrative, and Parajanov’s unparalleled vision is a soul cleansing experience. You feel the life of Sayat-Nova, even if you don’t fully understand the film’s story. If you do manage to follow every image on a literal level, then The Color of Pomegranates feels like the ultimate form of representation of another artist.

14. La noire de…

One of the finest films created in all of Africa, Ousmane Sembène’s La noire de… is a viscious depiction of colonialism boiled down to a single servant who is battling to live a better life. Back home in Senegal, Gomis Diouana is stricken with extreme poverty. In France, she is mistreated by her white owners who look down on her. In the meantime, a severance is created between her and her former life, as she loses connection with her loved ones. The bold title La noire de… insinuates that Diouana has to belong to somebody in this corrupted world, and she cannot exist strictly as an individual human being. Ousmane Sembène never minced his words when it came to how Africans were treated worldwide and even in Africa, so La noire de… isn’t exactly unfamiliar territory with him. However, with its simplicity, and powerful filmmaking that shines through its low budget, La noire de… remains his greatest statement.

13. Once Upon a Time in the West

Even though Duck, You Sucker! is an offshoot of a western film, Once Upon a Time in the West feels through and through like Sergio Leone’s farewell to the genre he helped bring to life. Spaghetti westerns usually rolled around in their grit, but this Leone epic felt more in tune with its soft side than anything else. That’s why its patience is much softer; we wait eternities for something to happen, and then bodies drop at the blink of an eye. Ironically, time for the west is running out, and yet we spend enough of it waiting to see who dies next. Creating the ending point of the wild west in brilliant fashion (including the villain-ization of one Henry Fonda), Once Upon a Time in the West concludes with the rise of a town and the ushering in of industrial America. The west hung on until the bitter end.

12. Andrei Rublev

With only his second film, Andrei Tarkovsky stunned the world with his philosophically enhanced filmmaking. With Andrei Rublev, he is more in touch with religion than ever before or after, whilst still battling his concerns with one’s individuality on Earth. Andrei Rublev is cleverly split into parables, thus continuing the religious sentiment, as we follow the titular icon painter through many stages of life (including one or two that are merely visions and have little to do with him directly). We never really see Rublev paint, but Tarkovsky — the other artistic genius named Andrei — showcases some work right at the end, bringing his legacy to life with complete glory. As epic as Andrei Rublev is, it’s more of an awakening than an undertaking.

11. Breathless

With all of the experiments Jean-Luc Godard fulfilled, none still feel quite as powerful as the very first film he made. I have no reason to have a bias towards Breathless, since I wasn’t even alive (or close to it) when it was released sixty years ago. Even if its moves aren't as daring as some of his latter works, Breathless still struck a harmonious balance between filmmaking and film-breaking that will forever remain captivating. With editing that goes against the foundation of what shots represent, cutaways from action to completely diffuse situations, and fourth walls never even existing, Breathless clearly was meant to be different like any other Godard or French New Wave film. In the meantime, Breathless feels beguiling with all of its “flaws”, like we've been celebrating cinema completely wrong until now.

10. Woman in the Dunes

Hiroshi Teshigahara’s Japanese New Wave opus Woman in the Dunes has always been loved; it continues to be one of the more daring Academy Award nominated features, especially in the bigger categories. However, today it continues to be loved, probably because of how many directors owe much of their success to Teshigahara’s innovation. Woman in the Dunes — a fable of identity and belonging — so exquisitely captures its images, that any second could be its own artwork to be hanged on a wall. Its context is much more daunting, placing unwilling participants in various exploitation-heavy scenarios. Woman in the Dunes is a philosophical journey to get subsumed by, and its magnetism has never let up.

9. Charade

Stanley Donen may have been known for his musicals, but one of his greatest achievements was apparently out-Hitchcocking Hitchcock after Psycho. Charade — all things considered — might be the ultimate genre bender in all of history, as it balances passionate romance, screwball comedy antics, whodunnit mystery, and even horrific thriller elements all at once. Its dialogue is a nonstop barrage of one liners and sarcasm, and its characters drop one by one. Playing with the idea of deception (likening lying to acting on the stage), Charade is also stuffed with many metaphors; the climax literally involves the stage. Charade’s own tone is as shifty as its untrustworthy characters, but what we do know is that it is as much fun as it is smart. What genre even is Charade at the end of the day? Let’s just call it Charade once and for all; nothing else is quite like it.

8. War and Peace

With the permission and help of the Russian government and army, Sergei Bondarchuk fulfilled the kind of dream many ambitious directors hope to pull off: the completely financed, time granted epic. War and Peace feels like the only way that the Leo Tolstoy tome could be created, and it took many years to make and release (the latter feat in individual parts over two years). The end result is over seven hours of mind blowing choreography, unbelievable direction, and jaw dropping visuals. The triptych tales of Andrei, Natasha and Pierre are split by the gargantuan French Invasion of Russia, but each character has their own fair share of complete devotion by Bondarchuk’s filmmaking; the tender moments in Natasha’s life, for instance, are extravagant. This was the last film of this kind, folks. There will never be another achievement like Bondarchuk’s War and Peace, most likely because the funding for it will likely never exist again.

7. Psycho

Alfred Hitchcock’s remaining features are mostly cult favourites or liked in their own right, but his final masterpiece, Psycho, sought to destroy the very system that embraced him to begin with. Doing away with a lead character halfway into a picture, focussing heavily on perversion and murder, and (gasp!) flushing toilets on screen were all a part of Hitchcock’s plan to bid Hollywood as we knew it a fond farewell. It took some years for other directors to catch on to this scale, but Psycho had to lead the way. Audacity aside, this also happens to be a massive achievement for Hitchcock, who was ushering in his own new age of extremely graphic horror; he never quite topped his filmmaking in Psycho with this era, though.

6. Lawrence of Arabia

The epic drama of all epic dramas, David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia is most certainly the kind of film of its kind that could never be made again. Could you imagine the hundreds of actors, horses and camels, and the shutdown of an entire city (or the creation of one, rather)? Lawrence of Arabia is an epic of old, but it became the best of its time long before there would become limitations on this kind of direction (CGI replaces many of these issues). All of this scope to bottle T. E. Lawrence’s complicated legacy as a historical figure of good and bad (depending on who you ask). With Peter O’Toole’s perfect portrayal of the officer (and some of the finest character development in film), Lawrence of Arabia was already fantastically made; it became untouchable.

5. 8 1/2