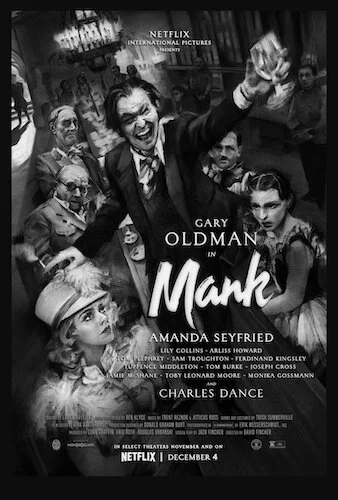

Mank

Jack Fincher was a Hollywood dreamer, who loved to channel the greats (and the misunderstood characters of yesteryear) in his screenplays. He wrote other forms of stories for a living — mostly articles — but deep down, between his move to California and his passion projects, film was in his blood. His heart was always appreciated, but there always seemed to be conditions. His Howard Hughes biopic became the basis of John Logan’s screenplay for The Aviator. Then there was Mank, which son David Fincher — who was living what feels like his father’s fantasies — always wanted to make, but he wanted to make the right way. Unfortunately, Jack Fincher passed well before Mank was finally put together, but you can see what son David was waiting for: technology to convincingly recreate ‘40s era cinema, the proper political climate for the screenplay to correlate with, and enough years to get out of his current crime phase and know how to treat these words just right.

A previous instance where David Fincher worked via soul rather than grit was The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, which is a noble but somewhat flat attempt at capturing the feeling that other auteurs just pull off effortlessly; don’t get be wrong, I do like Benjamin Button, but its flaws are a bit impossible to ignore. It was back to the drawing board for Fincher, who went forth into what I deem (and this is a spicy take, folks) to be his best era yet: the 2010’s. Between The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and Gone Girl (two of his most authentically captivating thrillers), his series that he worked on (House of Cards and Mindhunter), and his magnum opus The Social Network, Fincher has never been better for an entire era (don’t kill me for saying this). It was only time that he came forth and made a film like Mank with a completely different mindset. After Zodiac, he moved more gracefully through turmoil. After The Social Network, he became the kind of literary filmmaker he always wanted to be. Well, we can’t forget Fight Club and its self awareness, right down to the tiny easter eggs. That definitely plays a role here, too.

The visual style of Mank mimics the films of the ‘40s to great effect.

Mank is the culmination of so many experiences Fincher has had, boiled down to one of his biggest challenges yet: directing a film that’s not his usual fare. Without being completely unrecognizable, Fincher makes Mank a relatively passive film, fixating on each and every stepping stone in screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz’s journey towards crafting Citizen Kane. The biggest draw or setback — depending on who you are as a viewer — is Mank’s insistence on being a faithful series of tributes to Orson Welles’ masterpiece. Without any awareness of Citizen Kane, Mank is a strong-yet-quiet biographical picture that holds all of its cards for the very end. However, watch Citizen Kane, and you have mirrored moments (the dropping of a bottle being shot almost identically to Kane’s snow globe in its opening sequence, for instance), realizations for inspiration that slowly creep in (a stroll in the wee hours of the morning creates the exterior of Xanadu), and other important cues that Fincher doesn’t want to force feed to the unaware; he still wishes to reward cinephiles, though.

This notion continues through the impeccable visual style. Now, do I think Mank is a convincing illusion of being a film from the 1940’s or 1930’s? No, and I have an article as to why here. However, that doesn’t quite matter, because it’s as if Mank pulls off something even more special. Something that I always find uncanny about watching some old works — especially on film — is the light shining through the picture, creating cinematic ghosts of many folks that are all but a distant memory. The minimal blurring, the shadows so dark that they smear objects and beings together, and the piercing light all feel like a 2020 version of these ghosts. It’s obvious that Mank is a modern film between the sharp editing and the too-precise shots, so going for something a bit different was the right way to go. Even the “holes” in the film (meant to represent cues for a projectionist to change reels) don’t seem to fully capture what they’re meant to represent (a bit too small and too meticulous), but as an homage to a different time period, they’re sensational (the aforementioned problems are actually solutions to those that aren’t used to them).

Even against the integrity of the picture, Mank is willing to authentically capture the murkiness of dimly lit scenes during the Golden Age of Hollywood, and it makes for a powerful tribute.

This notion continues forth even more into the score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, who I don’t believe have ever worked so outside of their element than now. Gone are the brooding synths and existentially minimalist melodies, and here are the whimsical melodies of old Hollywood. Without going overboard on the sensationalism, Reznor and Ross, like Fincher, almost feel daring with how much they restrain themselves from going with the obvious mood selections. It’s a common theme that allows Jack Fincher’s screenplay to shine the most, and it’s clearly what David was hoping to accomplish the most after all these years: such a control on cinema, as to let certain elements gain the utmost priority without having a picture topple over.

This screenplay is an instance of like-father-like-son, since Jack’s writings are as sarcastic and self aware as the characteristics David would be permanently associated with. Jack channels the ghost of Herman J. Mankiewicz, who may have been forever jaded about the success of his greatest triumph being smeared by an arrogant Orson Welles, the titanic legacy of William Randolph Hearst, and the politics that got in between him and his film family. Mank is heavily a political picture, featuring the complicated rise of Upton Sinclair (flagged as a communist), economic recessions, and the use of film to create smear campaigns (as if Mankiewicz’s Citizen Kane was the ultimate version of anti-propaganda, against those that perpetrated filmic dishonesty). One very loose connection is how Mankiewicz based Charles Foster Kane on a number of tortured men of power, especially Hearst, but also including one Howard Hughes: the same producer that Jack Fincher was similarly fascinated with.

Herman J. Mankiewicz is depicted as a tormented soul that didn’t like to show that side of himself.

In a sense, Gary Oldman’s nuanced-yet-relaxed performance as Herman J. Mankiewicz allows the words (either by Jack Fincher or Mankiewicz himself) to speak for him fully; outside of alcoholic episodes, Oldman’s Mankiewicz says more with his physical reactions than the quick retorts he hid behind. Oldman is backed by a powerhouse cast, and everyone hits their mark; not only that, but they hit David Fincher’s mark. You see, as ambitious and expressive as Mank is, it’s also neutralized (but not safe), as if it was Fincher’s Spotlight. A director that’s as excessive and gloomy as Fincher being this Hollywood is frankly a bit strange, proving that we may sometimes take for granted how out there he is.

On the contrary, Mank still feels risky despite its relaxed exterior, never quite feeling safe. Rather, it is a chance for the viewer to notice every reference, feel every intention of the late Jack Fincher, and have an open world for people to live inside of: the utopia that the Golden Age pictures gave us. For all of that, it’s David Fincher working in his least comfortable state, but with the best intentions: homage, respect, and honour. Considering the many names and things that he did proud (Mankiewicz, Citizen Kane, the Golden Age, and, of course, father Jack Fincher), Mank is a triumph for the American filmmaker. As a straight up film, Mank is a gorgeous love letter to film, but previous knowledge of what it’s tethered to will truly allow both Fincher visions (Jack’s depiction of the forgotten, and David’s admiration for the perseverance of art versus business) to shine at their brightest.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.