Film History: Frames Per Second

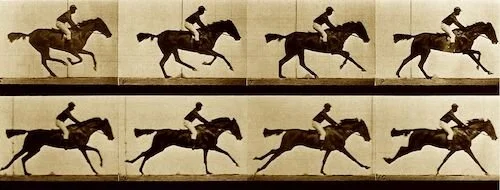

I was wondering what the very first film history lesson on Films Fatale should be, when it dawned on me. There is no better lesson than the very start of the cinematic medium, which was the discovery of the illusion of moving images. In return, this plays into how films have been perceived overtime, and the latest obsessions with the advancement of moving images. Film was actually a happy accident, invented by photographer and inventor Eadweard Muybridge. In 1877, Muybridge conducted an experiment with a horse, as he wished to examine the running and walking patterns of animals; part of this curiosity was to see if all of the hooves of a horse would be in the air at the same time mid walk or sprint. This experiment involved setting up a series of cameras with string triggers that would be set off by the horse as it walked past. While inspecting his footage, he discovered that having these closely related images in chronological succession could mimic movement. See the below video for an example of what this would have looked like.

Motion pictures are what we commonly call films or “movies” now, but that’s literally what they are: pictures that are in illusionary motion. Like any flip book or animation — which is based on the same findings of Muybridge’s study — film is actually a series of still images blasted in quick succession. This is how many movie “toys” (like the zoetrope) similarly work; illustrations or photographs can be spun to appear to move, and they continue for as long as intended, despite never actually moving at all. Even in the digital age, this has not changed, hence why you can extract still images out of video files through editing platforms. Each still image is more commonly referred to as a “frame”. The usual form of measurement is how many frames are shown in a second. In film, the standard is twenty four frames per second. It’s not exactly as many images as our brain interprets in a literal second, so that’s why film has its own feel to it (we will get into these specificities a bit later).

To break down what twenty four frames per second means at its barest form, here is a gif from Groundhog Day that we’re going to dismantle.

The above gif has fifty six frames in it. I’m going to cut out the first twenty four and lay them out one by one.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

If you scroll quickly enough and focus at one place, even these images may appear to move. Just for a comparison, here is a gif with just those twenty four frames, compared to the more complete fifty six frames in the previous gif.

The twenty four frame per second standard is important, because it makes sense for films to be uniform in a way that our brain is used to. Anything abnormal will stand out. We will get into what more frames per second looks like later. For now, let’s observe what fewer frames per second will do to a final product.

During the initial stages of cinema, films had much fewer frames per second, ranging between six and twenty, depending on the year, film, and other important factors. One of the earliest films ever made is Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory (and other variations of the same title) by the Lumière brothers.

The film was shot in sixteen frames per second, and you can see that the images are far choppier. Nothing happens in slow motion, but it also doesn’t happen quickly like it may appear. It’s actually just the choppiness of the image that makes each movement appear more jagged, thus quicker as a result. Part of this is because both cameras and projectors were hand cranked, which could open the opportunity for varying speeds. Standard projectors play at a set speed (obviously twenty four frames per second), so the footage of these silent works appears to be even more choppy (and “quick”) as a result. Having said that, adjusting a film to have more frames per second will affect the run time of said film. Before we get into that, here is the introductory scene to The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, which turned one hundred years old this year in February.

This film is shown at eighteen frames per second. I included it here, because it’s more refined than the above Lumiére brothers footage (although The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari presented in this clip is also in a raw state). My point is that there is still a clear choppiness after film became a narrative medium with more of a focus on visual style and presentation. From here on out, frames per second will be referred to as FPS.

Once sound recording was introduced as a part of filmmaking, the audio tracks distorted with the eighteen, sixteen, and other FPS variations. The human eye observes at roughly sixty FPS, but leaping from eighteen (or so) to that many images per second was a large leap in budgeting. It simply made no sense to spend that much on film. So, the lowest possible FPS was aimed for. Twenty four FPS was the absolute lowest a film could be before the audio track would begin to warp and wobble. Otherwise, with various FPS standards, sound will raise or lower in pitch (even both within the same film), or sound like it is being literally wobbled (which it technically was).

Seeing as the standard was set in 1927 during the dawning of sound in major motion pictures on a wide enough scale, a good example is Metropolis, which is one of the most worked on silent films of all time. Upon release, it was shown at a lower FPS, including sixteen, which can be seen below.

One of the numerous restorations has set Metropolis at twenty four FPS, partially so the recorded soundtrack (of the original score which accompanied screenings) would fit. The result is smoother, but the film itself is actually shorter. Reportedly, the exact same amount of footage of Metropolis played at sixteen FPS is 228 minutes long (or three hours and forty seven minutes), while twenty four FPS is around two hours and forty minutes. This is a major reason why early works of film are presented in length by the amount of reels they are, as opposed to time (as time is inconsistent here). Here is a trailer for a restored copy of Metropolis, presented in “twenty four” FPS.

So the standard was set from there on out. Twenty four frames have been used ever since, whether it’s in a clip like this,

or this,

or this.

What may be throwing you off (if these clips look vastly different) is the use of film stocks, the quality of the images, the types of cameras being used, and countless other factors. If you pay close attention to the actual fluidity of each scene, they are all twenty four FPS.

To get a modern look at lower FPS compared to the standard twenty four, here is an example found on the YouTube channel Nik Isa.

Now, in the last ten years or so, the topic of FPS has become a major discussion, mostly thanks to video games. Consoles and computers have upped the amount of frames per second their games can boast, so these particulates are important for video game consumers now. However, that isn’t to say that visual mediums haven’t been toying around with FPS all of these years. The biggest reason for this is not within the film community, but rather the rise of television. Television shows of varying sorts run at completely different FPS speeds, which is probably why watching the Super Bowl feels different to the commercials that play in between, and the HBO show you flip to once the game is done. I won’t even attempt to explain the basics of standard television FPS, because there is a YouTube video that has done so perfectly, thanks to the channel standupmaths.

Different television formats worldwide run at different FPS, and so do different recording formats. You’re looking at a range between twenty four to one hundred and twenty. However, film usually sticks to twenty four. That is until the wave of filmmakers that have tried to push the boundaries a little bit. Most notoriously, Peter Jackson displayed his The Hobbit trilogy at forty eight FPS: double the normal rate. The trailer below isn’t quite the intended speed, but it’s certainly at least thirty FPS or so, and you can still see a major difference.

You might need to play back the following video in HD for the FPS to work.

Didn’t this look smoother than usual? It was like Bilbo and company were in a soap opera, a reality show, a video game cutscene, or a sporting event. Your brain is taking in more images at a time. It’s an adjustment from what we’re used to with film. Let’s not forget that film is an illusion: these are all just still images being fired rapidly. If you look at film that way, it’s no wonder that boosting the FPS isn’t just a weird adjustment: it’s a possible headache, too. Imagine the bombardment your brain is taking on, especially when it is used to something much more easy to digest.

If that wasn’t enough, Ang Lee has also joined this phenomenon, but has gone even further. His latest film Gemini Man (which I could barely stand even at twenty four FPS) was released at three different FPS: the standard, sixty FPS, and a whopping one hundred and twenty FPS (the highest television can go). If you thought that Hobbit footage was a bit strange, take a look at the following clip, which is only presented at sixty (I couldn’t find an actual clip that was uploaded at one hundred and twenty FPS).

You might need to play back the following video in HD for the FPS to work.

Now that is an onslaught of images. While sixty is what the eye can see, and one hundred and twenty is what television can go up to comfortably, this — for me — makes for a jarring experience in a movie theatre. We’re also looking at films with a lot going on visually: large armies, action, and more. I think higher frame rates are something that can maybe be pulled off well, but I’ve personally not seen it at an appealing level yet in film. The good news is we no longer have to worry about audio tracks warping, thanks to digital film editing (so that doesn’t matter at all). However, this is a film history lesson, and from here on out is the future of film, which only time can tell us where that will go.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.