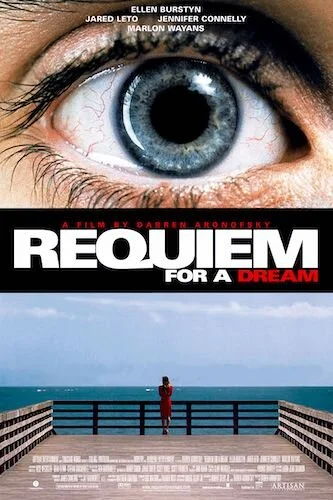

Requiem for a Dream: On-This-Day Thursday

Every Thursday, an older film released on this opening weekend years ago will be reviewed. They can be classics, or simply popular films that happened to be released to the world on the same date.

For May 14th, we are going to have a look at Requiem for a Dream

After the success of π, Darren Aronofsky was in a peculiar position: he was trapped in the newly found valley between indie film and the mainstream that was being created at the tail end of the ‘90s, thanks to distributors that brought low budgeted films to the big leagues. As a Harvard graduate, he was a major in social anthropology, despite his interest in filmmaking as well. He eventually trekked around the world to shoot what he could find, including seal studies and various communities. If you follow his social media footage, you’ll find more about his obsession with the world than his own film sets and experiences. Yet, you watch any of his works, and you’ll find an auteur that is fully driven by the cinematic experience. Even π, as limited budget-wise as it is, is an extreme effort in analyzing the human condition, and it does so with all of the aesthetic prowess that an indie film could muster.

The kicker is that the film is still heavily about humans as an animalistic species, within civilizations created with presumption. As advanced as people can be, they always resort to primitive tendencies; advancement isn’t the sole indication of intelligence, or a departure from what makes us animals. In π, the world connected a little too perfectly, and a smart mind couldn’t wrap his head around it. The Wrestler contains a performer consumed by his self destruction. Black Swan similarly featured an artist withering herself away. Mother! is the literal decimation of Mother Earth by humanity misunderstanding unity for hysteria. Then, there was Requiem for a Dream: an adaptation of Hubert Selby Jr.’s quadrilogy of downward spirals all driven by addiction. All four tales are based on substance abuse, but each drive is a different motive: survival, financial gain, pressure, and the quest to love one’s self after years of personal neglect.

Harry and Marion laying in a daze.

Aronofsky’s fixation on framing people as struggling animals is at its all time high here. From the very first frame, everything you see is an act of desperation. A son — and his best friend — pawn his lonely mother’s television to get yet another hit of heroin; they trip out to records on DJ equipment that could have been pawned instead. Mother Sara Goldfarb — while innocent during this — is clearly hooked on television, which is the addiction that gets overlooked by son Harry and friend Tyrone’s need for smack. Then there’s Harry’s girlfriend Marion (also a heroin addict) is chasing the dream of opening her own clothing store and being a designer; a virtuous desire stained by the sales of drugs in order to fund it. Tyrone is also hoping for a better life, out of the ghettos of Brooklyn. Sara has a completely different trajectory. She has been accepted to be a part of her favourite daytime show, and she wants to lose weight to look good to audiences watching nation wide. She has been instructed to take uppers; naive as she is, Sara gets hooked on pills but feels great. Plus, at the end of the day, everyone likes what they’re taking a part of when things are good.

Well, the dream gets squashed very quickly, but these downfalls don’t wrap up nearly as hastily. No. These four poor souls get stuck in a final act that simply won’t stop stabbing them while they are fallen. This is especially true, considering these are four storylines that take place at the same time, thus prolonging this climax. Clint Mansell’s now-famous score was melodramatic already, with the wailing strings that follow the film around. By this point, when this same string section becomes manic and disorienting, you feel as though you are on the verge of fainting, but your body won’t quit. You’ll wish you went unconscious or this all went away, but being caught in this limbo is a nightmare. Then, there’s Jay Rabinowitz’s congratulatory editing, which is some of the finest in cinematic history. The highs are punctuated with quick successions of images to indicate a rush. Otherwise, cuts are used to make you dizzy, turning Matthew Libatique’s rich visuals into a hallucination gone wrong.

Sara freaking out during the climax.

Like a nature study of an animal waiting to lunge towards its prey, the final act in Requiem for a Dream is the viewing party of four people that have hunted themselves and don’t even know it. They all curl up in the fetal position once resolution is finally reached. This isn’t a sign of rebirth. This is the desire to want to start life over, because this go-around was a failure for all involved. Each tortured spirit has a different fate: incrimination, the complete numbness of one’s self, bodily destruction, and the destruction of the brain. Identity, soul, body and mind are all corroded. The entire film is the passage of how all four characters arrived at this place. The finale is a compilation of implosions. Each player is now simply a husk of their former selves. Dreams simply don’t even exist anymore. The film’s title — and Mansell’s signature variations — is a representation of the demise of hopes. Each person chased addictions with other addictions. We may frown on them for their substance abuse, but we chase their other goals just as willingly: image, money, power and our career goals. Who are we to judge, especially if we are in better living conditions than the Goldfarbs and their loved ones?

Aronofsky was now in the cinematic stratosphere, as a filmmaker attached to greatly punishing works; he has not shed this identity since. Requiem for a Dream did decently reception wise upon release, whereas The Wrestler and Black Swan were awards season darlings. Today, Requiem for a Dream is twenty years old. If anything, I believe some of the more apprehensive responses two decades ago came from those that felt uneasy with this film, perhaps because an unrelenting indie filmmaker was given access to wider audiences. Again, this was that awkward testing period where the definition of “independent” cinema was greatly shifting. Look at the manic and cynical films that get cherished nowadays, by the Safdie brothers, Ari Aster, Yorgos Lanthimos and more. Aronofsky certainly wasn’t the first filmmaker to make films like this, but I feel like Requiem for a Dream was maybe the poster film to point at and blame during this weird fusion of indie, arthouse, and mainstream cinema happening in the late ‘90s and early ‘00s.

Really go back and look at the film now, if you’re not already a major fan of it. I’ve grown out of many films around this time that felt like a part of the similar club: Fight Club, Donnie Darko, V for Vendetta and the like. Label these “film 101” or “frat boy films” if you want, as I’ve heard these kinds of labels tossed around. Nevertheless, Requiem for a Dream feels much more powerful now than it did upon release, because Aronofsky and company were a part of a wave of films that simply didn’t happen yet. The older it gets, the more the shock fades and the art rises. Before I was repulsed by the sickness in the film. Now, I see all of the stunning photography, inventive editing, and the cleverness of the dialogue that seemed to be excessive initially.

Maybe Requiem for a Dream would be more than just a product of pop culture and dorm rooms if it came out in a different time, but it couldn’t have come out at a different time. Twenty years later, not much about this film feels full of itself or like an attempt to create a dialogue it can’t successfully depict (unlike its contemporaries discussed earlier). Requiem for a Dream is ideally Darren Aronofsky’s mainstream breakthrough, because it rightfully left a man misunderstood who would continue to polarize audiences ever since. Gaspar Noé, Nicolas Winding Refn and company aren’t nearly as well known as he is, and so Aronofsky really is most peoples’ exposure to filmmaking of such a difficult nature (although he is far from the most challenging filmmaker, I can assure you). If you’re still on the fence, give this film another chance. If you flat out hate it, I understand. If you already love it, I needn’t push anymore. Again, if you’re unsure if it has aged well or not, I certainly feel it has, especially in a time where the awareness of varying addictions outside of substance abuse is at an all time high, and the popularity of panic driven filmmaking is booming.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.