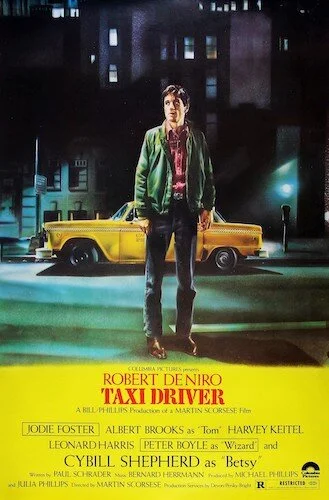

Taxi Driver: On-This-Day Thursday

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Every Thursday, an older film released on this opening weekend years ago will be reviewed. They can be classics, or simply popular films that happened to be released to the world on the same date.

For February 8th, we are going to have a look at Taxi Driver.

Contains Spoilers For Taxi Driver

There’s something about Martin Scorsese that budding cinephiles or the general movie going public seem to misunderstand: it’s assumed that he’s a pot stirrer that aims to get a rise out of his audiences via shock, when I can’t agree with that at all. Taking his entire filmography into consideration, you have a gorgeous period piece drama with The Age of Innocence, a family flick that is indebted to the history of early filmmaking with Hugo, a dark existential with After Hours, and so on and so forth. Sure, his gangster films seem to take the spotlight every once in a while when it comes to discussing his films, but that’s a given, seeing how he perfected the style. Even then, Goodfellas is a fashionable flick that isn’t necessarily meant to be driven by shock value, despite its upsets, gore and twists.

The primary suspect of why I feel like Scorsese gets this reputation is Taxi Driver: his New Hollywood masterpiece that remains an absolute rush to watch, orange-tinted blood-spilled climax and all. It’s the film that put him on the map of American auteurs for the rest of his career, despite his earlier successes like Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore and Mean Streets. The controversy surrounding Taxi Driver continues to this day, with films like Joker existing due to its innovations (and these works are often compared to the former, bringing its taboos back up every single time). What makes the film so effective, to me, is not how Scorsese or writer Paul Schrader fought to frighten or disturb audiences, but rather their knowledge of cinema through and through, and how they could tell a new kind of story through the same medium. It’s something modern audiences might take for granted now. The role of a character’s perspective in film was forever changed with the complex gazes of Taxi Driver.

We stay trapped in the mind of troubled veteran Travis Bickle.

The primary drive of the film is that its tone is neutral outside of lead character Travis Bickle’s influence (which overtakes everything). It’s a bit of a confusing angle, but it makes sense upon inspection. In a sense, Bickle paints himself out to be a hero throughout this picture, but the film that contains him — despite abiding by his voiceover narration and following his every move — disagrees. It’s as if we are getting two different testimonies at once, and it’s this feuding contrast between the storyteller and his story that sells the purpose of the picture: the depiction of extreme alienation to the point of psychosis, and the countless arguments that can be derived from this and only result in viciousness (can anything really be blamed for how Bickle winds up the way that he is?).

Bickle is a Vietnam War veteran, and his downward spiral is a commentary on the way that governments don’t necessarily take care of the defenders of their freedoms; Bickle’s experiences are juxtaposed with the upcoming presidential election, and much of the story gets intertwined with the campaign of senator Charles Palantine. Bickle is exhausted by the uncleanliness of New York City, but his initial concerns about the dangers of the streets dives into other pressing worries that hinge on racism and other problematic thoughts. It’s evident extremely early on that we aren’t meant to be sympathetic for Travis Bickle (an idea that I feel like still gets lost on people), but we’re meant to understand one of cinema’s most corrupted characters. He’s clearly affected by battle, and that’s where we start. The state of his surroundings and the lack of leadership is part of the equation, but Bickle’s collapsing judgement is the sum of a multitude of problems, and I do think some are self inflicted.

Travis’ terrible date with Betsy.

A number of plot threads begin to make this concept extremely muddy (intentionally so). There’s Bickle’s fascination with Betsy (a young volunteer for Palantine’s campaign), which Bickle means well with but is insanely creepy about; this ranges from his stalking which is meant to be sincere, and his lack of common sense when he brings her to a pornographic picture (it must be normal since he’s seen women at these movie houses before). On one hand, he is disturbed and is clearly in need of help (of which he isn’t getting). On the other, he’s still a frightening guy who is a danger to people like Betsy. Another plot thread that complicates matters is his vigilante pursuance, as he learns about a juvenile prostitution ring that he wishes to dismantle by himself. This proves that Bickle isn’t the worst person in the film (balancing him out as an antihero and not a straight up villain), but he’s still in the rankings for the most broken.

These two trains of thought converge in the blistering finale. While Bickle is a budding terrorist that vows to murder senator Palantine, he’s also trying to be the saviour of the underage victims of human trafficking. It’s a bizarre conflict of traits that still manage to pair nicely together; Bickle is still violent and worrisome, but one goal is clearly entirely bad, and the other is bad but with the best intentions. It’s a major reason why this character is still widely talked about: how bad is Travis Bickle? Everything we see stems from mental illnesses that aren’t being treated, but we can’t condone what he’s doing. He promises to kill, but he’s the hero of the day in his mind. We’re left with a very distraught narrator right in the middle of the New Hollywood movement that was getting rid of the limitations of the Production Code. Many films have had narrators tell the story we are seeing, but why couldn’t that be shattered along with everything else in cinema?

Isolation is a key theme in Taxi Driver.

The extents that Taxi Driver takes to prove its narrator is impossible to trust are great in length. The fact that Bickle’s inner thoughts are as tired as he is (he can’t even conjure up a lively version of himself) says it all. His voiceover drones monotonously. It even stumbles over itself, as if it’s reading something and lost track of where it is (fantastic acting by Robert De Niro, of course). The voiceover also illustrates the exact opposite of what we’re seeing, or it says something that’s not quite on the same page as us; Bickle’s thoughts corner us into hearing uncomfortable proclamations. The camera’s gaze is part of the illusion as well. When the film zooms in on an alka seltzer tablet fizzing in a glass (the sound of said tablet also overtakes Bickle’s mind audibly), you understand his drifting mind that zones out at any given time.

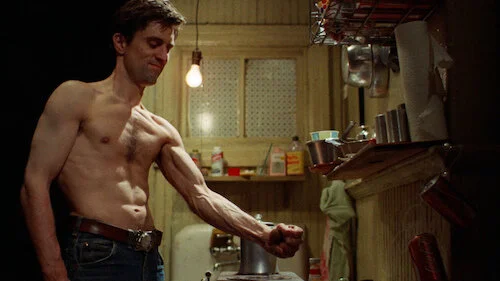

The film goes an extra mile with other factors, like the iconic “Listen you fuckers…” moment where the film relapses and starts this moment over again; even in his own mind, Bickle is fragmented enough to not be able to hold a complete thought without having to backtrack (that cut frightens me a little more than what he’s saying, because he is completely unable to control his mind). The aftermath of the climax is also heavily debated: is Bickle actually dead, and the finale is all just a fleeting thought of his new life whilst passing on? Scorsese and Schrader have claimed that this isn’t a vision from the afterlife, but it is meant to be literal. I have to ask: literal in what sense? In the same way that the entire film is confined in the mind of a psychopath?

Perhaps it’s still in lieu of that element. However, the finale doesn’t share the same self awareness of the entire rest of the picture, where the film isn’t in agreement with Bickle. Post-climax, Bickle gets the girl, is a proven hero, and viewed exactly how he wanted to be viewed (even by the film itself). Regardless of what has been said, I personally feel like the aftermath is all a hallucination during death, but am happy with the possibility that Bickle’s sick mind has overtaken the perspective to the point that the film no longer can pry itself away from his corruption.

Bickle’s efforts to get tougher and be unstoppable.

Everything else about the film wavers in-and-out; from realization to detachment. Bernard Herrmann’s iconic score is occasionally a smooth replication of the music of New York (a smooth saxophone to guide us through the night) or a pounding onslaught of anxious calamity. The cinematography by Michael Chapman can be varying shades of brown and grey, or it can be illuminated by the same New York City streetlights that plague Bickle (but shine on us). The editing by Marcia Lucas, Tom Rolf and Melvin Shapiro is sleek and yet it feels choppy exactly when it needs to; as if we’re watching a state of mind slowly wither away. The back-and-forth states of all of the film’s aesthetics is cognizant of the unreliable nature of its lead character, who dominates the entire picture. It’s about capturing the beauty of life and the scum within it (but not necessarily the kind of people Bickle considers to be scum, since I’d argue he’s a part of this umbrella term).

Taxi Driver is fascinatingly strange, because it almost feels like an open diary written by a demented, aspiring assassin who has spilled his guts for us to wallow in. Otherwise, it’s a film that happens to be dictated by said character, and it aims to keep its distance for its own sake. This results in Bickle’s isolation and existential depression stinging stronger. In a very disturbing way, there are elements of all of us in Bickle, but anyone trying to liken themselves to him is missing the point, I find. Do we all feel cast away by life and society? Sure. Do we all suffer from loneliness and fall prey to the darkest corners of our minds, especially when we fend for ourselves? Of course. Do we all feel worthless when we fail, despite our best efforts? Yes.

However, Travis Bickle is the culmination of all of these ideas, plus the unhealed PTSD and lack-of-help that he deserved as soon as this film started. He is a character far gone from normalcy. You’re not meant to cheer. You’re not meant to gawk. Bickle is here to witness, and witness alone. He’s telling you he’s a hero. The film states otherwise. He is driving a car that isn’t his, whether it’s the cab that he uses for a living, or a story that was only meant to feature him that surveyed the people of New York City. Instead of a goody-two-shoes lead, we have a run down veteran with a death wish. Instead of a happy ending, we don’t even know what is going on here. Instead of a plot, we have a man who creates his own fate and collapses into the lowest psychological sickness possible. This is as New Hollywood as it gets, and comparing it to how other Hollywood pictures get received just doesn’t make perfect sense. Taxi Driver remains controversial not just because of its subject matter (which any director and writer could do), but because of its frigid state, lack of conventional formula, and bastardization of the warmth that Hollywood forced you to feel for your entire life. That can only be done by masters of this craft.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.