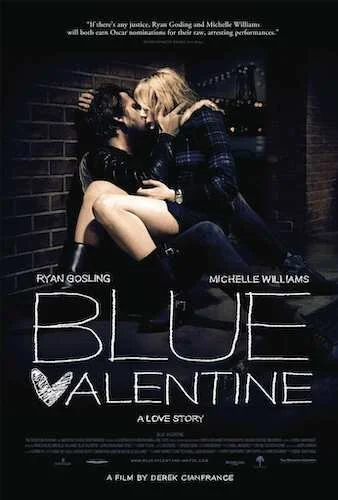

Blue Valentine

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

There are awards season darlings that get carried around by every hand of every academy, until these festivities are over; these works then get dropped like hot potatoes, and abandoned for the years to come. This doesn’t happen to every acclaimed juggernaut, as the best films usually manage to contain their prestige and succeed until the end of time. But there are still this batch of films that we all forget about, or the big dogs just don’t talk about as much anymore. The obvious Oscar bait films vanish in time, as their true intentions and focus on awards above art or quality shows. What about the films that aren’t made for these reasons? The actual dark horses that get neglected and shoved in the same corner as Oscar bait films, despite their qualifications?

Blue Valentine, to me, has been this kind of film: an independent drama that did incredibly well in the 2011 awards season, and then was sadly ignored, even though it warrants the attention of all. As far as I’m concerned, this is the finest film Derek Cianfrance has put out to date, and a big reason why is his balance between the two different timelines that Blue Valentine bounces between throughout its duration. It’s clear what each moment is meant to feel. The younger days of two people falling in love are warm, with hints of red, salmon, pink, and other nurturing tones. The characters feel a bit more naive. The love is exciting, and the sex is adventurous. Whenever we cut to the present day, we see how cold everything now is. Blues and teals dominate everything we see. Characters are monotonously cynical. Sex is a chore, and love is non-existent. It’s an obvious set of parallels, but Cianfrance makes this work effortlessly by making each memory clash with the present in other ways: reminders of the butterflies in one’s stomach, the things that used to make us laugh and now destroy us, and a life of promise winding up withering and awaiting death.

The flashbacks in Blue Valentine are saturated and warm, with reds and pinks hinted everywhere.

The way the film is split also forces you to face reality basically as soon as the picture starts: if the “red” storyline is Dean and Cindy falling in love, then the “blue” is their relationship’s demise. The flashbacks still aren’t perfect, with Cindy’s ex boyfriend trying to get back into the picture, but you still know that the present is meant to be a complete contrast; this means glimpses of joy, but they’re far less prevalent than the lingering gloom of the past that clouds over the freeness of love. Ironically, Dean and Cindy try to find love again in a thematic motel which features a “future” room; how can they ever get to the future if the present isn’t working out? There are also revelations that effect each timeline, like the main “twist” of the past that might make you rethink how you feel about characters or predicaments (I found the flashbacks to make Dean more sympathetic than his current self ever could, for instance).

Matching the indie feel is the indie music of Grizzly Bear, whose songs (including instrumental cuts of works like “Foreground”) are a gorgeous contribution to the film. The emotional stature of these works and their stripped down feel feel almost like the zenith of the baroque pop rock works that were attached to independent features of the new millennium, as if the blurred line separating individual songs from scores finally pulled off the intended illusion. Adding to this full package are the producer and acting contributions of Ryan Gosling and Michelle Williams: two acting powerhouses that still take preference with indie pictures, likely because of how much they allow them to get emotionally invested. Gosling is explosive but keeps trying as Dean, whereas Williams is the shut-off Cindy; the chemistry (or toxicity, rather) that brews between the two of them is melodrama magic. Both Gosling and Williams improvised a good portion of their actions and dialogue, resulting in an extensively raw experience (both through love and through despair).

The present day scenes are cold and feel lifeless, with the smallest hints of heart (like the dashes of “red” above).

Is it fun to watch a marriage fail so viciously? It’s even harder when the sexual scenes are so incredibly explicit for their time; it’s like Blue Valentine is so excessively vulnerable to the point of extreme discomfort. That might not be everyone’s cup of tea, but it’s a truth about great divorce dramas, not solely about Blue Valentine. A recent frame of reference people might have is Marriage Story, but if you look at the best films of this kind like Scenes From a Marriage or A Separation, and you’ll see that misery is a main ingredient of this genre. My favourite parts of Blue Valentine are the awkwardly charming scenes to balance the entire picture out, and add something innocent in between the graphic sex and the harrowing depression. One such scene is the song-and-dance number, where Dean has to “sing goofy” in order to perform well, and Cindy tap-shoes to his ukulele playing. It’s the kind of event you’d see downtown in the wee hours of the night, and you’d gaze upon this couple and admire the love between them; if only you know where this could lead.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.